In 1698 the Parlement of Dijon found a Catholic priest guilty of engaging in sex with members of his flock. Philibert Robert, the cleric in question, characterized the sexual abandon he and the women experienced as a devotional act that brought them closer to God. If that’s not an arresting opening hook for a scholarly book, I don’t know what is! Robert and his followers were Quietists, adherents of a theology that explored the individual’s ownership of herself and feared an obsession with consumer goods might ultimately alienate people from their true identities as selfless fragments of a divine whole. As a spiritual practice that links self-surrender to a rejection of too much stuff, one can’t help but wonder if Quietism could be the missing link between Marie Kondo and E. L. James. Suffice it to say, Charly Coleman’s lucid, insightful book, The Virtues of Abandon: An Anti-Individualist History of the French Enlightenment, arrived at an ideal moment.

Essays

The Immanent Frame publishes essays reflecting on current events, debates in the field, and other public matters relevant to scholarship in secularism and religion.

The Immanent Frame typically publishes essays by invitation only. To see our open calls for content, click here.

To read essays from our archive that are written by scholars introducing or reviewing a recently published book, click here and here.

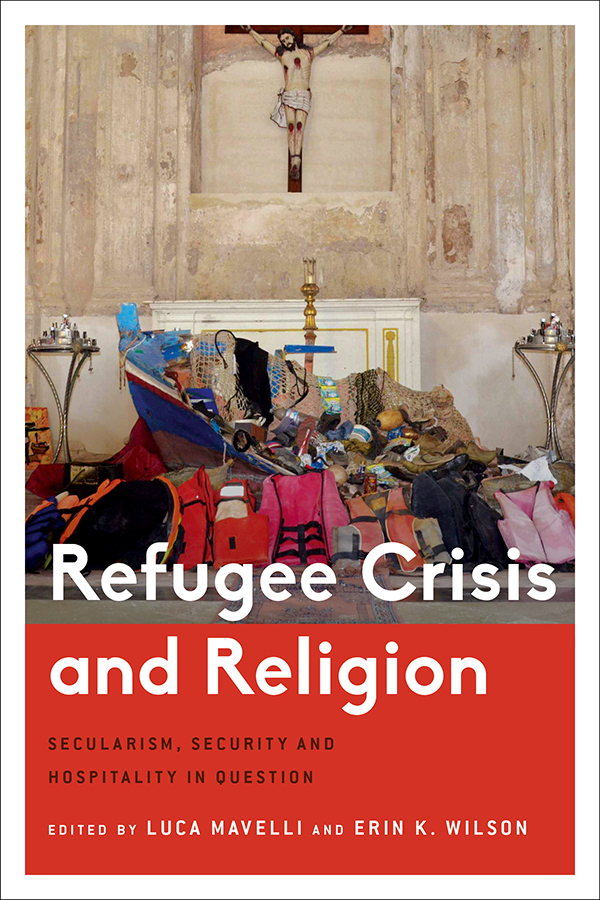

The refugee crisis and religion: Beyond physical and conceptual boundaries

by

Erin K. Wilson and Luca Mavelli

by

Erin K. Wilson and Luca Mavelli

According to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), as of the end of 2015, 65.3 million people were displaced globally at a rate of twenty-four persons per minute. This is the largest number on record and is expected to have grown in 2016. Despite the enormity of the situation, responses from Western countries (who host a mere 24 percent of displaced persons in comparison to the 86 percent hosted in countries surrounding conflict zones) have been inadequate, to say the least. Their harsh exclusionary rhetoric has resulted in increasingly hardline immigration policies. Australia has led the way in this regard, deploying a deterrence-driven model of offshore mandatory indefinite detention, which prevents asylum seekers from ever settling in the country, even if found to be “genuine refugees,” and laws that make family reunion almost impossible. Whilst this approach has been condemned by the UNHCR and multiple human rights organizations, it has been highlighted by numerous policymakers in Europe as a possible model for governing migration on the continent. Despite the notable exceptions of Germany and, to a smaller extent, Italy, European responses to the crisis have privileged exclusionary and securitizing policies, leading many commentators to observe that rather than a refugee crisis, this should be more properly described as a crisis of leadership or a crisis of solidarity.

Muslim Cool: An introduction

by Su'ad Abdul KhabeerThe book focuses on interminority relationships to articulate a narrative of race and racism in the United States that transcends the Black-White binary and also the fallacy of postracialism, which holds that racism, particularly anti-Black racism, is over and that any talk of race is actually counterproductive to the work of antiracism. I identify the ways in which race, and specifically Blackness, is marshaled in the work of antiracism. For Muslim Cool, Blackness is a point of opposition to white supremacy that creates solidarities among differently racialized and marginalized groups in order to dismantle overarching racial hierarchies. Yet as the stories in this book illustrate, these solidarities are necessarily entangled in the contradictions inherent in Blackness as something that is both desired and devalued. The engagement with Blackness by young US Muslims, Black and non-Black, is informed by long-standing discourses of anti-Blackness as well as the more current co-optation of Blackness in the narratives of United States multiculturalism and American exceptionalism.

Race, secularism, and the public intellectual

Who counts as a black Christian public intellectual? There are certainly public figures who are not intellectuals, and there are intellectuals whose primary audience is in the academy. Similarly, when adjectives are…

Islamic and Jewish Legal Reasoning: An introduction

by Anver EmonIslamic and Jewish Legal Reasoning: Encountering Our Legal Other is a curious book, in part because it came out of a working group that seemed the least likely vehicle for producing a collection of articles in book form. For five years, sponsored by the University of Toronto and Canada’s Social Science and Humanities Research Council, approximately six Rabbinic law scholars and six Islamic law scholars sat around a table with various legal texts from their respective traditions and talked, discussed, and queried. As a protocol of discussion, we would have the scholar of one tradition introduce the text of the other tradition. In other words, a Rabbinic scholar would introduce the Islamic legal text, and the Islamic law scholar would introduce the Rabbinic text. This process precluded anyone from claiming expertise over what the text “says,” and instead created a space of openness, engagement, and even play. The endeavor was not designed to make us into scholars of our tradition’s Other, but rather to experience (in the most robust sense of that word) the encounter with our legal tradition’s Other.

The Weimar Century

by Or RosenboimThe international turn in intellectual history, which David Armitage announced in 2014, has evolved into a surge of publications on the global, international, and transnational aspects of the history of ideas. The migration of concepts around the world and moments of conceptual conjunction in history have attained growing attention from historians. Although methodological nationalism had never been the only option for writing the history of a specific country or society, it seems that now an international perspective is indispensable for explaining the political, cultural, or economic history of any given country. Historians seek to put their finger on the complex, dynamic moments which generate and reverberate influential ideas around the world. The patterns of relationship between different social, cultural, and political spheres, and the exchanges that lead to the evolution of ideas and concepts across national boundaries, have become increasingly appealing to historians of all creeds. Udi Greenberg’s The Weimar Century: German Émigrés and the Ideological Foundations of the Cold War can be read as a contribution to this growing literature on international intellectual history.

Trumping reality

Why those who support Trump do so can be captured by perspectives on income, not income itself; by perspectives on race and immigration, not by racial identity; by a sense that everybody…

God in the Enlightenment

by Simon BrownIn a speech before the Brexit vote, Boris Johnson offered a controversial historical pedigree for his campaign to leave the European Union. He insisted that the Leave campaign members were not all backward Little Englanders but rather deserved the reputation as the real upholders of the “liberal cosmopolitan European enlightenment.” He and his colleagues inherited the tradition, he claimed, because they too were “fighting for freedom.” An interview Johnson gave a year earlier, when he claimed that London and Paris shared a commitment to “enlightenment and freedom,” offers some indication about what that “freedom” entailed. He described how these values assured the right to open expression, even when that expression might critique religions and provoke “would be . . . jihadis.” Johnson’s evocation of the Enlightenment testifies to the continual contest over its political meaning and to its deep associations with anti-religious critique. The contributors to God in the Enlightenment, edited by William Bulman and Robert Ingram, offer nuanced narratives to articulate a “usable” Enlightenment whose meaning can help us arrive at a more sophisticated understanding of the relationship between religion and secularity in public debate.

An exceptional tradition? The Jesuits in the world

In September of this year, the president of Georgetown University, John DeGioia, issued a formal apology for the 1838 sale of 272 slaves. When compared with other universities built on the backs…

Race and Secularism in America

by Grace GoudissOn September 13, 2016, Clemson University’s head football coach Dabo Swinney was asked what he would do if one of his players refused to stand for the national anthem. San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick had recently done so, explaining that he would not “stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color.” Swinney took issue not with Kaepernick’s message, but with his method. Dismissing Kaepernick’s refusal to stand as “distracting,” Swinney deployed the image of Martin Luther King Jr. as a model of “the right way” to protest. Swinney’s words immediately sparked controversy. Clemson professor Chenjerai Kumanyika responded with an open letter to Swinney, sharply titled “Take MLK’s name out your mouth.” He chastised Swinney for participating in a long, misguided heritage of sanitizing King’s radicalism, and of corrupting King’s legacy for the purposes of white moderate liberalism. “In the face of the injustices in his own time,” Kumanyika writes, “Dr. King called for direct action, not press conferences.” The editors of Race and Secularism in America, Vincent Lloyd and Jonathon Kahn, would not be surprised by this marshalling of Martin Luther King Jr. and his legacy, nor by the fact that this legacy is constantly contested and renegotiated along lines of protest, race, and religion. Indeed, in the collection’s introduction, the King monument in Washington, DC serves as a towering symbol of the complex relationship of its two subjects—race and secularism—and their analytical inextricability. King is central to the collection’s claim: Because “whiteness is secular, and the secular is white,” “the careful management of race and religion are the prerequisite for accepting the public significance of a fundamentally raced religious figure.” Indeed, the collection takes as its central stance that secularism itself is primarily a (white, liberal) game…