Even quite sober academics speak of “a contemporary crisis of secularism,” claiming that “today, political secularisms are in crisis in almost every corner of the globe.” Olivier Roy, in an analysis focused on France, writes of “The Crisis of the Secular State,” and Rajeev Bhargava of the “crisis of secular states in Europe.” Yet this is quite a misleading view of what is happening in Western Europe.

Even quite sober academics speak of “a contemporary crisis of secularism,” claiming that “today, political secularisms are in crisis in almost every corner of the globe.” Olivier Roy, in an analysis focused on France, writes of “The Crisis of the Secular State,” and Rajeev Bhargava of the “crisis of secular states in Europe.” Yet this is quite a misleading view of what is happening in Western Europe.

Each country in Western Europe is a secular state and while each has its own distinctive take on what this means, there are, nevertheless, two main historical strands of secularism, a main and a lesser strand. The latter is principally manifested in French laïcité, which seeks to create a public space in which religion is virtually banished in the name of reason and emancipation, and religious organizations are monitored by the state through consultative national mechanisms. The main Western European approach, which I call moderate secularism, however, sees organized religion as a potential public good or national resource (not just a private benefit), which the state can in some circumstances advance—even through an “established” church. Its public benefits can be direct, such as a contribution to education and social care through autonomous church-based organizations funded by the taxpayer; or indirect, such as the production of attitudes that create economic hope or family stability, or that contribute to conceptions of national identity, cultural heritage, ethical voice, and national ceremonies.

Western Europe has often been a site of struggle between historical public churches and political secularists, yet during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, especially during the latter and especially in Protestant-majority societies, this has not been deeply conflictual and has taken the form of various shifting compromises. The compromises consisted of a successful accommodation of an expanding number of Christian churches within the actual and symbolic workings of the state, yet were marked by a gradual but decisive weakening of the public and political character of the churches. From the 1960s through the end of the century, there was a particularly strong movement of opinion and politics in favor of the secularists. In Western Europe, the cultural revolution of the 1960s has been broadly accepted; not only has there been no major, sustained counter-movement, but it has expanded beyond north-western Protestant/secular Europe into Catholic Europe. So, for example, the national system of ‘pillarization’ in the Netherlands, by which Protestants and Catholics had separate access to some of the state’s resources, emerged in the nineteenth century, declined sharply in the middle of the twentieth, and was formally concluded in 1983. The Lutheran Church in Sweden was disestablished in 2000. In the UK, disestablishment of the Church of England was embraced in the early 1990s by key sections of the center left. Catholic countries—Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Ireland—in the 1980s and 1990s rapidly showed signs of the secularization characteristic of Protestant Europe.

There is no endogenous diminution of secularization in relation to organized religion, attendance at church services, and traditional Christian belief and practice in Western Europe. Whether the decline of traditional religion is being replaced by no religion or by new ways of being religious or spiritual, neither mode is inspiring an attempt to connect with or reform political institutions and government policies. There is no challenge to political secularism there.

This is the context in which non-Christian migrants have been arriving and settling and in which they and the next generation are becoming active members of their societies, including making political claims of equality and accommodation. As the most salient post-immigration formation relates to Muslims, some of these claims relate to the place of religious identity in the public sphere.

It is here, if anywhere, that a sense of a crisis of secularism can be found. The pivotal moment, 1988-89, of this “crisis” was marked by two events. These created national and international storms, and set in motion political developments which have not been reversed, and they offer contrasting ways in which the two Western European secularisms are responding to the Muslim presence. The events were the protests, in Britain, against the novel The Satanic Verses by Sir Salman Rushdie; and, in France, the decision by a school head-teacher to prohibit entry to three girls unless they were willing to take off their headscarves on school premises.

The Satanic Verses was not banned in the UK, so in that sense the Muslim campaign clearly failed. In other respects, however, it galvanized many to seek a democratic multiculturalism that was inclusive of Muslims. The Muslim Council of Britain (MCB) was established and has been very successful in relation to its founding agenda. By 2001, it had achieved its aim of having Muslim issues and Muslims as a group recognized apart from issues of race and ethnicity and of itself being accepted by government, media, and civil society as the spokesperson for British Muslims. Another two achieved aims were the state funding of Muslim schools on the same basis as Christian and Jewish schools and getting Tony Blair—in spite of ministerial and civil service advice to the contrary—to insert a religion question into the 2001 Census. This meant that the ground was laid for the possible later introduction of policies targeting Muslims to match those targeting groups defined by race, ethnicity, or gender. The MCB had to wait a bit longer to get the legislative protection it sought, yet by the time New Labour left office in 2010, it had created the strongest protection against religious discrimination in the EU, including a law against incitement to religious hatred, the legislation most closely connected to the protests over The Satanic Verses, though there is no suggestion that the novel would have been banned by the legislation. Indeed, the protesters’ original demand that the blasphemy law be extended to cover Islam has been made inapplicable as the blasphemy law was abolished in 2008—with very little protest from anybody. These developments have taken place not only with the support of the leadership of the Church of England, but in a spirit of interfaith respect. (Given how adversarial English intellectual, journalistic, legal, and political culture is, religion in England is oddly fraternal and little effort is expended in proving that the other side is in a state of error and should convert.)

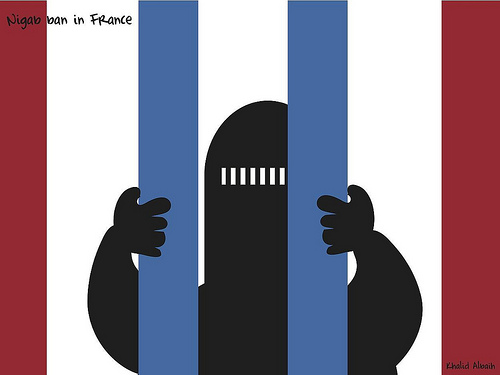

That is one path of development from 1988-89. It involved the mobilization of a minority group and the extension of minority policies from race to religion in order to accommodate the religious minority. The other course of development, namely, that which arose from l’affaire foulard, was one of top-down state action to prohibit certain minority practices. From the start, the majority of the country—represented by the media, public intellectuals, politicians, and public opinion polls—was supportive of the head teacher who refused to allow religious headscarves in school. Muslims either did not wish to or lacked the capacity to challenge this dominant view with anything like the publicity, organization, and appeal for international assistance that Muslims in Britain brought to bear on Rushdie’s novel. The threatened ban against the headscarf was passed with an overwhelming majority by Parliament in February 2004. A few years later, the target of secularist and majoritarian disapproval was focused on full face veils that leave just the eyes showing (the niqab or burqa), as are favored by a few hundred French Muslim women. This was banned in public places in April 2011. Belgium followed suit in July 2011 and Italy is in the process of doing so. Similar proposals are being discussed by governments and political parties across Western Europe.

Another example of this broad anti-Muslim coalition is the majority that voted in a referendum to ban the building of minarets in Switzerland in 2009. Analysis of this majority has explained that it ranges from individuals whose primary motivation is women’s rights to those “who simply feel that Islam is ‘foreign,'” who may have no problems with Muslims per se but who are not ready to accept “Islam’s acquiring of visibility in public spaces,” or who generally did not vote “out of a desire to oppress anybody, but because they are themselves feeling threatened by what they see as an Islam invasion.” So, prejudiced or fearful perceptions of Islam are capable of uniting a wide range of opinions into a majority, including those who have no strong views about church-state arrangements, as indeed has been apparent since Muslim claims first became public controversies.

This means that the current challenge to secularism in Western Europe is being debated not just in terms of the wider issues of integration and multiculturalism but also in terms of a hostility to Muslims and Islam based on stereotypes and scare stories in the media that are best understood as a specific form of cultural racism that has come to be called Islamophobia and is largely unrelated to questions of secularism.

The crisis of secularism is best understood, then, within a framework of multiculturalism. Of course, multiculturalism has few advocates at the moment and the term is highly damaged. Yet the repeated declarations from the senior politicians of the region that “multiculturalism is dead” are a reaction to the continuing potency of multiculturalism, which renders obsolete liberal takes on assimilation and integration with new forms of public gender and public ethnicity, and now public religion. Muslims are late joiners of this movement, but as they do so, it slowly becomes apparent that the secularist status quo, with certain residual privileges for Christians, is untenable as it stands. We can call this the challenge of integration rather than multiculturalism, as long as it is understood that we are not just talking about an integration into the day-to-day life of a society but also into its institutional architecture, grand narratives, and macro-symbolic sense of itself. If these issues were dead, we would not be having a debate about the role of public religion or coming up with proposals for dialogue with Muslims and the accommodation of Islam. The dynamic for change is not directly related to the historic religion nor to the historic secularism of Western Europe; rather, the novelty, which then has implications for Christians and secularists, and to which they are reacting, is the appearance of an assertive multiculturalism which cannot be contained within a matrix of individual rights, conscience, religious freedom, and so on. If any of these were different, the problems would be other than they are. Just as today we look at issues to do with, say, women or homosexuality not simply in terms of rights but in a political environment influenced by feminism and gay liberation, within a socio-political-intellectual culture in which the “assertion of positive difference” or “identity” is a shaping and forceful presence. It does not mean everybody is a feminist now, but a heightened consciousness of gender and equality creates a certain gender-equality sensibility. Similarly, my claim is that a multiculturalist sensibility today is present in Western Europe, and yet it is not comfortable with extending itself to accommodate Muslims, nor able to find reasons for not extending itself to Muslims without self-contradiction.

Political secularism has been destabilized, and in particular the historical flow from a moderate to radical secularism and the expectation of its continuation has been jolted. This is not because of any Christian desecularization or a “return of the repressed.” Rather, the jolt is created by the triple contingency of the arrival and settlement of a significant number of Muslims; a multiculturalist sensibility which respects “difference”; and a moderate secularism, namely, that the historical compromises between the state and a church or churches in relation to public recognition and accommodation are still in place to some extent. To speak of a “crisis of secularism” is highly exaggerated, especially in relation to the state. It is true that the challenge is much greater for laïcité or radical secularism as an ideology. As many social and political theorists are sympathetic to this ideology, and in any case, being more sensitive to abstract ideas, they are less able to see that the actually-existing-secularism of Western Europe, with the exception of France, is not the radical variant. They thus mistakenly project the incompatibility between their ideas and the accommodation of Muslims onto the Western European states. Indeed, as applied to Western Europe, “crisis of secularism” is not only exaggerated but misleading. As I hope I have shown, the problem is more defined by issues of post-immigration integration than by the religion-state relation per se. The “crisis of secularism” is really the challenge of multiculturalism. Far from this entailing the end of secularism as we know it, moderate secularism offers some of the resources for accommodating Muslims. Political secularists should think pragmatically and institutionally about how to achieve this, namely, how to multiculturalize moderate secularism, and avoid exacerbating the crisis and limiting the room to maneuver, by pressing for further, radical secularism.

A longer version of this essay was first presented as the Paul Hanly Furfey Lecture, delivered in Las Vegas on August 19 at the Annual Meeting of the Association for the Sociology of Religion.

As a graduate student focusing on secularism, religion and politics, I find very much interesting in the debate and exchange between Tariq Modood and Rajeev Bhargava. Modood, in his piece “Is there a crisis of secularism in Western Europe?”, basically argues that, yes, there is a crisis, but it should not be exaggerated. He offers a revised version of secularism, “moderate secularism”, for correction and institutional adjustment to new developments in Europe. In his understanding, talk about crisis is debatable and unnecessary. Bhargava, by contrast, in his piece “Beyond Moderate Secularism”, claims that, yes there is a crisis and it is much more profound than we actually think. While agreeing on many points with Modood, he says that the issue is beyond institutional adjustment “because an internal link exists between the collective, secular self-understanding of European societies and deeply problematic institutional arrangements”. Bhargava believes that unless the current understanding of secularism has been changed “with an altogether different conception of secularism”, there is no way to challenge to current challenge in Europe.

While their exchange enriches our understanding, I find that their intervention is highly abstract and assumes that the situation in Europe will stay as it is today in coming years. My aim is not to produce counter-arguments to their claims, but I hope to re-phrase the question of secularism in the light of current developments in the Middle East, namely the Arab Spring. I accept that we are still at the very beginning of the change in the Middle East and there is no guarantee that popular revolutions will result in a perfect democracy and economic development. However, for the sake of enriching our debate on secularism in Europe, we may consider that the Arab Spring will change the social settings in the Middle East.

In essence, both Modood and Bhargava agree that the ‘crisis’ of secularism today is a direct result of diversification of European societies, mostly Muslim immigration to Europe and, last but not least, state policies towards their accommodation or assimilation into European societies. What happens if (Muslim) immigrants decide to return to their own countries? Can the Arab Spring contribute to the debate on secularism in Europe? If yes, in what way? If not, why not?

Debate on secularism has never been immune from the sociological, historical and political context in which the term is defined. Debate on citizenship, secularism and immigrant participation will not be settled until the conditions that brought immigrants to Europe are solved. They went to Europe for a better economic, political and social condition which did not exist in their own countries. They have not migrated to Europe because they ‘love’ the host country; rather they did so because of other social, economic and political reasons.

Now with the Arab spring, the issue is set to be a bit more complicated. For example, the rise of Turkey as an example (or model for a possible Muslim democracy), along with an economic development and deepening democracy, is giving more hope for immigrants to return to their own countries. In the last several years, many Turkish immigrants living in Sweden have moved back to Turkey. According to the director of the Swedish Institute in Istanbul, as she told me recently at a conference in Stockholm, this trend is likely to continue in the coming years.

How could the Arab spring shape the immigration debate and reverse the ‘brain drain’ in Europe? It is difficult to assess as of now. However, it is likely that immigrants will have a chance to decide whether they want to live in the host country or their home country. Reasons that caused immigration to Europe in the first place may reach a point where immigrants start to re-consider going back to their home countries. Indeed, the worsening economic environment and increasingly hostile and even Islamophobic tendencies in Europe may accelerate this process. This may result in a healthy way of thinking for immigrants, as they are likely to choose to live wherever they love, like and want to be. So then the result may be a ‘normal’ and ‘love’ marriage for immigrants in Europe, rather than a ‘forced marriage’ as we see it today.

Considering the deepening economic crisis in Europe and the possible future implications of the Arab Spring, I would like to pose the following questions to Bhargava: (a) Will the possible return of immigrants to their own countries strengthen the traditional concept of secularism (i.e. strict separation of religion and politics) in Europe? (b) Or by alleviating Europe from the current political context – the issue of immigration and their integration (or assimilation) – will this development give a chance (or an ideal opportunity) for Europe to face the issue directly, and maybe face itself too?

There are also several questions related to Modood’s concept and approach: (a) How will the return of immigrants shape the debate on secularism itself and the concept of moderate secularism? (b) What will be, if any, the influence, setbacks or positive impulses of the secularism debate in the Middle East when immigrants get back to their own countries? (c) Will immigrants be hesitant to support and promote the concept of secularism in their home countries because of their negative experiences in Europe? Or would they be supportive of it considering positive experiences in Europe?

There is already an ongoing debate on secularism in the Middle East after Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan suggested in his Arab Spring tour in September 2011 that secularism would be the best way forward. Many people, including Egypt’s powerful Muslim Brotherhood, have criticized this suggestion arguing that Egypt has its own unique history and background in religion and state relations. It is worthy that those who think about the future of secularism in the West consider both the current ongoing secularism debate in the Middle East and possible repercussions of the Arab Spring on Muslim immigrants in future.