Post-election reporting that 79 percent of white evangelicals voted for Mitt Romney got little attention in the news because most journalists thought it wasn’t news. Evangelical support for the GOP has been consistent; even Romney’s Mormonism didn’t put them off. So election analysis approached white evangelicals as it usually has: as religio-political lemmings, all voting Republican for all the same reasons.

Post-election reporting that 79 percent of white evangelicals voted for Mitt Romney got little attention in the news because most journalists thought it wasn’t news. Evangelical support for the GOP has been consistent; even Romney’s Mormonism didn’t put them off. So election analysis approached white evangelicals as it usually has: as religio-political lemmings, all voting Republican for all the same reasons.

Yet where there was once the appearance of a monovocal evangelicalism there is now robust polyphony—what theologian Scot McKnight calls “the biggest change in the evangelical movement at the end of the twentieth century, a new kind of Christian social conscience.” This deserves our attention because most politics does not happen at elections but in between, when policy is negotiated and implemented. Current shifts in evangelical activism have re-routed the flow of evangelical money, time, and energy, and are changing the demands on the US political system. This essay investigating the shift is based on seven years of field research in evangelical books, articles, newsletters, sermons, and blogs, and on interviews with evangelicals, ages 19 to 74, across geographic and demographic groups—from students in Illinois to retired firemen from Mississippi, from former bikers to professors and political consultants (see The New Evangelicals: Expanding The Vision Of The Common Good).

For the purposes of this essay, American evangelicalism is an approach to Protestantism across denominations, its central features including: the search for a renewal of faith toward an “inner” personal relationship with Jesus; the mission to bring others to this sort of personal relationship; the cross as a symbol of not only salvation but also of service to others; individual acceptance of Jesus’ gift of redemption; individualist Bible reading by ordinary men and women; and the priesthood of all believers independent of ecclesiastical or state authorities. It was a progressive movement from the colonial era to World War One. Its emphasis on individual conscience made it anti-elitist, anti-authoritarian, economically populist, and socially activist on behalf of the common man. Twice in the twentieth century, evangelicals turned to the right, the second time in the late 1970s, when they became a central pillar in the modern conservative movement.

But recent trends point to another political transformation within this community—to those evangelicals who have left the right, moving toward an anti-militarist, anti-consumerist focus on poverty relief, environmental protection, and immigration reform, and on coalition-building and more issue-by-issue policy assessment (more Democrat on environment, for instance, and more Republican on abortion). While the religious right remains robust, in 2005 Christianity Today lambasted evangelicals for conflating the gospel with American or Republican policy, writing, “George W. Bush is not Lord… The American flag is not the Cross. The Pledge of Allegiance is not the Creed. ‘God Bless America’ is not Doxology.” In 2006, the Evangelical Environmental Network/Call to Action, launched its “What would Jesus drive?” campaign for greater fuel efficiency. In 2007, the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) issued its “Evangelical Declaration against Torture.” Since 2009, the NAE has repeatedly protested against Republican budget cuts for the needy, for instance writing, “this is the wrong place to cut.”

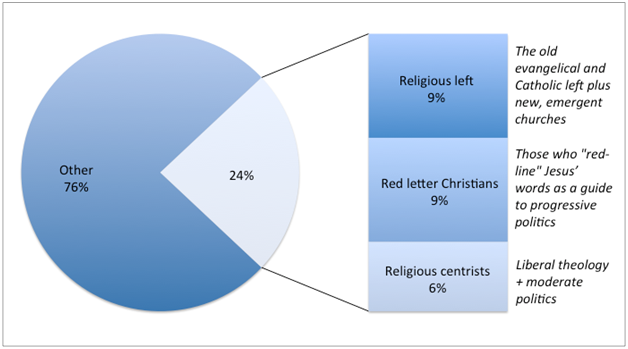

These “new evangelicals,” as Richard Cizik, head of The New Evangelical Partnership for the Common Good, calls them, are neither small in number nor elite. By 2004, devout Christians whose activism differs from that of the religious right came to 24 percent of the US population. Subtract Catholics, and we find that 19 percent or so of devout Protestants do not identify as religious right.

Devout Christians whose activism differs from that of the religious right (% of US population). Source: Assessing a More Prominent ‘Religious Left.’ Pew Forum for Religion and Public Life (June 5, 2008).

Four factors were decisive in this shift. The first is generational, with idealistic younger evangelicals rejecting the in-group-ism and Prosperity Gospel politics of their parents. They are, as then-AP religion writer Eric Gorski found, “even more anti-abortion than their elders” on ethical grounds, “but also keenly interested in the environment and poverty.” Second are cultural changes since the 1960s. Attitudinal shifts—about the environment, global connectedness, and poverty—have proceeded not at the radical fringe but in Middle America, and priorities there, including among evangelicals, have shifted. Third is ethics amid a group that takes ethics seriously. The militarism and torture of the Bush years and the consumerism and in-group-ism of the last forty years prodded many evangelicals to self-examination. In their book, Unchristian, evangelicals David Kinnaman and Gabe Lyons title their chapters Hypocritical, Sheltered, Too Political, Judgmental, and Antihomosexual, giving some idea of the self-critique underway. A fourth reason is the de-professionalization of service work. As growing numbers of ordinary Christians began to live and serve among the poor, their priorities moved toward economic justice and environmental protection.

One key feature of “new evangelicals” is their embrace of church-state separation in order to ensure fair government and religious freedom for all, including Muslims. As the Evangelical Manifesto (2008) declares: “Let it be known unequivocally that we are committed to religious liberty for people of all faiths… We are firmly opposed to the imposition of theocracy on our pluralistic society.” This document was signed by over 70 evangelical leaders, including the president of the National Association of Evangelicals, Leith Anderson, and Mark Bailey, president of the Theological Seminary in Dallas, Texas.

A second key feature is self-identification as a critic of government when they believe government to be unjust. This is the “prophetic role” of the church—not to be government but to “speak truth to power.” And it requires party independence. In 2006, Frank Page, then president of the conservative Southern Baptist Convention, warned, “I have cautioned our denomination to be very careful not to be seen as in lock step with any political party.” The 2008 Manifesto, too, called on evangelicals to distance themselves from party politics, lest “Christians become ‘useful idiots’ for one political party or another.”

A third feature is self-identification as civil society actors (neither state actors nor “bubble communities”) who advocate for their positions through public education, lobbying, coalition-building, and negotiation. Indeed, “new evangelicals” are often engaged more than other citizens in the economic, social, and charitable spheres of American life through the programs they develop. These are run largely by volunteers who also raise much of the programs’ funds. As one Midwestern pastor explained, “If healing the brokenhearted, setting the captives free, and ministering to the poor was Jesus’ job description, then we believe it is ours as well (Interview with the author, May 1, 2009; September 25, 2010).

These programs are not only giving alms, but are also seeking to restructure opportunity—in education, health care and clean air and water. Evangelicals do this first within the church. An example would be the over 200,000 Christians who contribute to a pool that covers members’ medical bills, handling over $12 million in medical expenses a year. Reaching outside the church, evangelicals alter their business practices toward economic justice. An example would be the Pasco, Washington fruit farmer who puts 50-75 percent of her profits into development projects in the US and abroad. For her employees she built a residential community and set up ESL, GED, and computer courses, parenting training, youth programs, counseling services, preschool and elementary school, and a college scholarship program.

“New evangelicals” also use their own monies to redistribute resources in less developed regions. Examples include the educational, substance abuse, homeless, environmental protection, and micro-credit programs that are run not only by large organizations like World Vision, whose micro-credit program supports over 440,000 projects in forty-six developing countries, but by volunteers in local churches. One church in my study spends $1.5 million a year on economic justice and aid programs. Another runs an impressive free health clinic locally and raised $66,000 to build a training center in a Zambian village, plus $100,000 for yet another project.

In their overseas endeavors, these evangelicals are developing a nuanced critique of the “Bibles for bacon” school of evangelizing, where participation in religious activities was a condition of aid. This is unacceptable not least because when Jesus served, he did not ask people “to sign on the bottom line,” according to John Ashmen, head of the Association of Gospel Rescue Missions (Interview with the author, December 22, 2010). One head of a church overseas mission said, “We tend to everyone—Muslim, Jewish.” If people want to know why his church is digging a well or building a school, he’ll tell them. Perhaps something about his faith will interest them. If not, “I’ve dug thirty foot water wells with guys who didn’t believe what I do, and I love those guys. If God wants to use me to change their belief, that’s fine. If not, then heck, we dug a well” (Interview with the author, May 1, 2009).

“New evangelicals” also oppose anti-gay discrimination in housing, education, and non-religious employment. They note that while some consider homosexuality a sin, a matter between man and God, democracies do not punish people for sins, which after all vary across faiths. Moreover, the state does not rescind civil rights for the commission of other sins, such as heterosexual adultery—why should it then for homosexuality? They note also that judging the sins of others is unchristian. A joint evangelical-Catholic Washington Post OpEd protesting Uganda’s draconian anti-gay legislation declared, “any effort to persecute people for their sexual orientation or gender identity offends intrinsic human dignity and violates Jesus’s commandment to love our neighbors as ourselves.… The entire Judeo-Christian worldview is built on this unshakable foundation.”

While 74 percent of white evangelicals oppose gay marriage, opposition to gay civil unions is decreasing: at 57 percent in 2009 and dropping; and less than a majority—41 percent—of evangelicals who attend church less than once a week oppose. In 2011, evangelical Belmont University amended its anti-discrimination policy to include homosexuals, and recognized its first gay student organization. That same month, the student newspaper at Westmont College ran an open letter signed by 131 gay and gay-friendly alumni in support of gay students. Alumni at the influential Wheaton College have a Facebook page in support of gay students.

While 60 percent of white evangelicals opposed abortion in 2012, 34 percent believed it should be legal in all or most cases. Noting that 73 percent of US abortions are economically motivated, “new evangelicals” aim to provide accessible, realistic alternatives, including medical, financial, and emotional support during pregnancy along with day care and job training post-partum, where needed. Especially effective programs include pairing a pregnant woman with a local family to serve as her “family” and help out as needed, for instance, driving the child to day care when the new mother’s car has a flat tire so that she can get to work and not lose her job. Midwestern megachurch pastor Greg Boyd explained, “A person could vote for a candidate who is not ‘pro life’ but who will help the economy and the poor. Yet this may be the best way to curb the abortion rate” (Interview with the author, May 4, 2009). “New evangelicals” note that there is no reason why they should not join with others, including feminists, in developing these programs. “I am decidedly pro-life,” southern megachurch pastor Joel Hunter says. “But by working together instead of arguing, both sides can get what they want.”

Though GOP policies are often at odds with “new evangelical” activism, the “new evangelical” vote remains largely Republican in part because of reluctance to back a party that supports legal abortion. In greater part, however, it is a vote for small government. This is a preference that evangelicals came to through doctrine and history, beginning with the Protestant and evangelical emphasis on self-responsible striving for moral uplift. While this originally meant striving toward the divine, striving became a muscle well-exercised and applied to many arenas of life, including the political and economic. Striving was further underscored for dissenting (evangelical) Protestants, who became determinedly self-reliant in order to survive the oppression and marginalization by Europe’s states and state churches. These qualities—a preference for individual and community self-responsibility on one hand, and the dissenter’s suspicion of authorities on the other—interacted synergistically with the rough nature of American settlement, where one could not rely on authorities or the state because there was little of either.

Because of evangelicalism’s formative influence on American culture, these elements remain broadly influential even today. The American political imaginary is one of voluntary associationism and suspicion of central government. In spite of the Great Recession, support for a governmental safety net is down 18 points since 2007. For evangelicals, this is even more the case. If they are generally wary of the state, Obama’s use of government programs to address recent economic crises further inflamed their mistrust. To be sure, the 2008 election saw an uptick in evangelicals supporting the Democratic Party: two evangelical ministers—Joel Hunter and Tony Campolo—helped write the 2008 Democrat party platform; Leah Daughtry, an evangelical minister, served as CEO of the 2008 Democratic National Convention Committee; and evangelical PACs like the Matthew 25 Network were set up to support Obama. Kirbyjon Caldwell, the influential Houston pastor, gave his support to Obama, though he had given the benediction at both of Bush’s presidential inaugurations and presided at the wedding of Bush’s daughter in May, 2008. Wilfredo De Jesús, pastor at New Life Covenant church in Chicago and staunch opponent of abortion and gay marriage, supported a Democrat, Obama, for the first time in his life. But while these gestures of support translated into an increase in evangelicals voting Democrat—a third of white evangelicals under 40; 26 percent of older white evangelicals; 36 percent of the less observant—a mass turn to the Democrats is at present unlikely owing to small-government-ism and opposition to abortion. What raises more serious questions, however, is the 65 percent of evangelicals ages 18-30 who favor more governmental aid to the needy, including Obamacare. These questions may endure, with implications for the political future, as coming-of-age politics has life-long effects.

White evangelicals, because of their small-government-ism, are often seen as un-modern and unequipped to deal with today’s economic and geo-political complexities. It is an ironic view, as their extensive social service work has made many of them sophisticated in their understanding of economic, environmental, medical, and migration issues, including the relations among poverty, soil erosion, rapes of girls out alone searching for potable water, AIDS, and migration. It is also worth noting that evangelicals do not call only for smaller government, but for a more robust civil society; not only for an absence (of central government), but also for our energetic presence.

A nice article. I wonder what would change about the author’s conclusions had she included African American, Latinos/as, and Asians in her equations. Evangelical does not automatically equal white, and I imagine that such conclusions drawn from that limited demographic should be questioned.

Given that this is posted at The Immanent Frame, it might be worth noting that Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age provides another hint at how to understand this: see chapter 17 on the reverberations of the “anthropocentric turn.”

What remains to be seen is whether these “new” evangelicals don’t just turn out to be “old” liberals. Taylor’s analysis, of course, would equally see the Religious Right as a “misprision” of Christianity. But that doesn’t mean a “progressive” Christianity is the only alternative. Ross Douthat, in Bad Religion, articulates a critique of the Religious Right without buying into the dichotomy would conclude that the only other alternative is to be “left.”

What’s puzzling to me is how many young evangelicals, telling themselves they are non-partisan or non-political, end up pretty much identifying with just another political agenda—of the left—in the name of “tolerance,” “justice,” etc.

Very interesting article, Marcia. I am an Anglican Christian, so I am not of the Evangelical tradition. As you know my Episcopal Church has taken a leadership role for the greater inclusion of LGBT people in the life of the church. My own parish is a charter member of the Oasis Movement within the church to provide greater affirmation of all human beings no matter what their race, economic level, or sexual orientation within organized religion. We would be considered pretty left wing even within the Episcopal Church itself. We like to think the rest of the church is just beginning to catch up with us. Bishop Gene Robinson (the first openly gay bishop within the Anglican Communion) believes that thoughtful members of conservative churches want to find a way around their heretofore negative approach to gay people. Your article would only confirm his thoughts. In fact I would extend this to other issues as you have pointed out of the environment, poverty, and social justice. Let us all walk in love as Christ loved us and gave himself up for us as a sacrifice and offering to God.

Pace James Smith, was remains to be seen is if the “new evangelicals” aren’t simply, and temporarily, the kinder and gentler face of *conservative* evangelicalism. I wonder if this demographic portends a turn to the Left seems misguided. Being “pro-life” sets them on the far side of the left, new or old, and that seems unlikely to change. Likewise on homosexuality; new evangelicals might not see this as the defining issue of the church, and they might be more inclined to recognize civil unions, but they aren’t united on this, and it seems many still consider “it” a sin, again setting them apart from the Left. Witness the reaction to Louie Giglio’s “withdrawal” from the inauguration. Last, sure they advocate “small-government”—now that a Democrat is in the White House and the last evangelical Christian President supported war crimes they really couldn’t ignore—but it’s reasonable to ask how long they remain aloof to state power. Just because this movement addresses issues long championed on the Left—poverty and the environment—doesn’t mean it is being seduced to a new alignment in the culture wars. It could just as easily mean that a new generation is adapting to changing demographic and political trends, in part by expanding what counts as an evangelical vision and adjusting its older vision to cope with a loss of a political and public platforms. And of course citing Ross Douthat favorably does little to support your analysis.

Thank you. Your insightful article helps to bolster the spirits of folks who have all but given up on any political respect for Evangelicals to continue our mission of representing liberal social policy as more inclusive and acceptable.

I have always found distasteful irony in the recent fashion of demanding laws enforcing one’s strictly religious beliefs, particularly from an element born from such religious enforcements being placed upon them. I most ardently support the voice of all religions being considered in legislation, but it is nice to see some indication of defection, in fact pushback, from Evangelicals who acknowledge not only that theirs is not the only voice in a multicultural, secular society, but also that the voices claiming to represent them politically may not be accurate.

As you pointed out in the article, the idea of winning hearts and minds for Jesus seems to be removing itself from the mood for buying or bullying it. I will encourage this as much as I can find a way to, and articles such as this encourage me to try.

James KA Smith, as one of these ‘new’ evangelicals I can tell you that it isn’t a matter of ‘identifying with just another political agenda.’ When the conservative party begins to applaud the preventable death of another simply because they have no money to pay the doctor…where should we go except away?

When the conservative party accepts and condones abuse and torture in the name of their own safety…where should we go except away?

When the conservative party has become anything BUT conservative…where should we go except to those who, at the very least, give lip service to economic and social equality?

Keeping the gays in the closet is NOT more important than finding money to feed hungry children. Keeping birth control away from promiscuous women is NOT more important than providing mental health services to the homeless. There are a great many issues that the Republican Party stands for that I support, but not at the expense of others.

For me, this isn’t a matter of politics…it’s a matter of personal and religious integrity. But then, I guess I’m more the ‘do unto others’ kind of Christian and not a ‘consume them in wrath’ type.

As an ‘old’ liberal, politically and theologically, I’m fascinated by the shifts and changes taking place among the many evangelical movements. The increased focus on care for those in need (e.g., affordable health care) and oppressed (e.g., LGBTI and those tortured by our government) seems a welcome change from past decades in which these children of God took a back seat to the desire to score political victories and gain political power. Will this result in greater cooperation and understanding between political/theological liberals and conservatives, or do those terms now grow increasingly irrelevant?

Mara Dobbins, I appreciated your thoughtful take on religious and personal integrity.

I find this article interesting at numerous levels. As an evangelical myself, I find these shifts at once heartening and disheartening. I find them heartening because there is a hope that we can choose not to align ourselves with a party wholly as a religious movement. When we give ourselves over to a party within the system, then we can easily be co-opted into being subjects to that party. On the other hand, I am somewhat disheartened by what James K. A. Smith mentions as the tendency to simply move from one side to the other. What we need is a healthy critique as Christians, and evangelicals in particular, of the powers, rulers and authorities. Of course, this touches into what Niebuhr addressed in his classic book, “Christ and Culture,” which is a critical, yet often un-addressed, aspect of this discussion. The “what” of our interaction with political, social, and cultural issues must be informed by a healthy understanding of the “why” of such interactions.

This article speaks well to the cognitive dissonance many Evangelicals perhaps feel when confronting their faith and politics. While not an Evangelical myself, I am a student of religion and have been very interested in this growing number of Evangelicals that are leaving the right. Perhaps this shift may also lead to parties that are more moderate by having constituencies that are not as hardline on the issues. However, there are many academic articles and research that disagrees on how large and powerful this movement really is. There was an interesting study done by the Pew Forum in 2010 regarding the link between people’s beliefs and their political views. Religion seemed to have little influence on people’s views regarding immigration, poverty and the environment. Evangelicals seem to approve of stronger laws regarding the environment, but their religion does not seem to be influencing this. However, there are less Evangelicals that are in favor of policies that give additional help to the poor. There is an interesting situation going on here in what issues trump others, as the article speaks to how the desire for smaller government comes ahead of many other issues for Evangelicals.

Another interesting facet of this fragmentation is perhaps looking at the rhetoric this new movement may use. I know the Evangelical Environmental Network launched a campaign a few years back that used the language of “pro-life” to support EPA pollutions standards. This launched a fierce backlash from the religious right who said this type of rhetoric would confuse voters. Both groups obviously still share beliefs about abortion and gay marriage as stated in this article. But their rift over other issues raises the problem of who will “own” Evangelical rhetoric in the public and political spheres. This may lead to a bitter fight in the future. However, presently this break is a very interesting phenomenon.

Marcia Pally’s concept of the “New Evangelicals” brings refreshing insight to a usually monotonous and stereotypical concept of Republican Christianity. This large shift of evangelicals, twenty-four percent, in regards to activism different from that of the religious right can have strong repercussions in the political world and could possibly trigger a realignment of political views from the Right. Generational and cultural changes, ethics and de-professionalization of service work have all played significant factors in spurring this shift. It seems like the new generation of American society as a whole is learning towards certain more liberal social issues (i.e. environmental issues that will eventually become norms for all citizens regardless of political affiliation). Jesus as a guide to progressive politics could serve as a strong link between religiously devout and secularists because such aligning interests could provide a common ground to better unify these groups as conscientious American citizens rather than divided by religious affiliation.

New Evangelicals seem to be just one result of a phenomenon of this generation of young adults in America passionate about making progressive changes for the betterment of the country, but also a generation who is much more tolerant than their predecessors. In this day and age there exists a plethora of different religions, different races, and different points of view about the world we inhabit and Americans are growing seemingly much more accepting of their peers, neighbors, friends etc. holding different opinions and beliefs. We hold so many more identities that we no longer just identify as a Catholic or an Asian, but rather you can be an environmentally passionate, Buddhist, African-American student. Having multiple identities can create conflicting interests and certain compromises have to be made to uphold these various identities (i.e. a female Evangelical who believes that abortion should be legal(.

Such concessions are necessary to function and prosper in the type of civil society that Pally notes. New evangelicals contend the optimistic notion that working together with non-evangelicals so all sides can get what they want is achievable if Americans begin to focus more what bonds them together rather than constantly highlighting differences. We need to negotiate more with each other. If more Evangelicals start shifting certain political views, then a realignment of interests in the Republican Party will have to take place to hold on to their primary voters. This could completely redefine the Republican Party’s platform in a way that might make them more in tune with social issues and appeal to a younger voting demographic. Or a new group other than the Evangelicals could come to dominate the Right and Christian issues like stem-cell research and abortion might wane and become less controversial in the future. However, it is too premature to predict whether this trend of leftist-activist evangelicals will continue and what exactly its influence will be on politics.

The New Evangelicals movement is an attempt by younger generations to reconcile the modernistic ideology that they hear in school or among their peers with value-centric religious upbringing. Many of them do this by taking a fresh look at the bible to justify their unorthodox methods. For example, when they do evangelical work in impoverished countries, they do not implement the “Bibles for bacon” methods in which they do volunteering in exchange for religious compliance. Instead, they let their actions speak on their faith’s behalf and attempt to win over the native populace by example. As opposed to the typical coercive church methods of evangelization, this way minimizes cultural imperialism while still adhering to the scripture. Another example is the New Evangelicals’ take on abortion. Even though New Evangelicals are even more anti-abortion than their counterparts, they see alternative solutions to the problem rather than merely voting for conservative candidates. Many New Evangelicals believe that abortions happen more frequently when there is a lack of education and social support. As such, they might vote for a pro-choice candidate whose platform focuses on the above issues despite the candidate’s position. As pastor Greg Boyd said, “A person could vote for a candidate who is not ‘pro-life’ but who will help the economy and the poor. Yet this may be the best way to curb the abortion rate.”

A second way in which the New Evangelicals reconcile liberal thought with religious tradition is with an increasing comfort with a dichotomy between the secular state and the religious private life. A prime example of this is how they deal with homosexuality. Although New Evangelicals may privately believe homosexuality to be sinful, they understand that it is not the place of the state to punish sins. As such, they are far more relaxed about gay marriage than their typical evangelical counterparts. Also, two of the three “key features” of New Evangelicals that the article mentions have to do with a separation of religion from the state. The first of these is the embracement of religious pluralism in American society and the willingness to admit that, as Brad S. Gregory might put it, there are alternative answers to “life questions” that are found in other religions. The second key feature is that the Church must not be the government, but be a critic of it. Although the way it was phrased in the article was as a warning not to be manipulated by any one political party, it also shows an understanding of the distinction between the domain of the secular state and the domain of religion. This position is fairly different from that of several conservative leaders in the United States who espouse Christian political theology.

The New Evangelicals are very forward-thinking in their approach to politics. They realize that the old school of thought regarding religion and political conservatism is slowly becoming outdated and unpopular and that, in order to stay relevant, their religion must adjust to them times.

Pally’s portrayal of the New Evangelicals gives hope to those of us (including myself) who have been soured by the media’s one-sided, biased representation of Evangelicalism. What I find most promising is the New Evangelicals’ willingness to work across party lines as well as with multiple religious affiliations. The current era has become defined by the obdurate temperament of both Republican and Democratic parties and their stark opposition to having a genuine conversation with the opposing party. This growing trend of unyielding to compromise has been detrimental to the country’s efforts to move forward. Thus, that such an “un-modern”, in Pally’s words, body of people has taken measures to compromise on issues as important to them as abortion and homosexuality should not be lost on us. The work of the New Evangelicals should serve as a model to the rest of our polarized nation that only by working together can any progress be made. One can only hope that this signals the early developments of increased cooperation across political and theological lines.

That being said, I appreciated Pally’s use of the phrase “coming-of-age” because I feel this wholly is a coming-of-age story for Evangelicalism. This shift away from the right demonstrates a people’s willingness to change in order to remain relevant; at the same time, I feel that it is a sign of maturity of the people. It is never easy for human beings to admit that the current structure or ideology of a system is inhibiting the success of the system. Yet, in this day and age, when religious pluralism and the diversification of race, ethnicity and sexual orientation is the norm, a uni-vocal frame of mind can no longer sustain itself because people will increasingly feel unconnected and ostracized from the group. The hyper-criticalness of the Evangelicals has given way to self-examination and a relabeling of what in-group and out-group should mean. When a majority no longer exists, what do minorities become? Though I think that my generation has many downfalls, the openness and acceptance that exist in the current epoch go unparalleled. I’m in agreement with Pally that the younger generations have played a huge role in what I find a promising shift of the Evangelicals away from the right.

Marcia Pally’s article is a refreshing examination of evangelicalism in America. Pally challenges and complicates the perception of evangelicals that is portrayed in popular media. Evangelicalism is often linked with unbending Bible-based social conservatism and right wing politics. However, Pally shows that this is not the whole picture. Rather, the term “evangelical” is an umbrella term that encompasses quite a wide range of diverse individuals.

According to Pally, evangelical is a term for a type of religious commitment, not necessarily a type of political viewpoint. In fact, describing them all as conservative right wing republicans is inaccurate because, as Pally points out, many “new evangelicals” would identify as evangelicals but do not hold the political social beliefs usually associated with evangelicalism. Furthermore, it is inaccurate to assert that all evangelicals want to infuse the political and public sphere with religion. As Pally explains, “new evangelicals” actually endorse the church-state separation as a way of ensuring religious freedom for all Americans.

Pally’s article shows that “evangelicalism” is far more than modern media make it out to be. Evangelicals today are a diverse group with different beliefs. This article really challenges the view of evangelicalism as an indicator of conservative republicanism and presents it as the type of religious belief that it truly is.