Around Christmas time, in the heart of Europe, furor broke out over blasphemous cartoons. The newspapers and public opinion were split. Was the blasphemer a public martyr for “liberty of the Press, or the right of free speech and free thought”? 1Daily News, March 2, 1883 Or did the cartoons represent a “gross and gratuitous insult to the religious convictions of others”? 2Birmingham Daily Post, March 5, 1883

Around Christmas time, in the heart of Europe, furor broke out over blasphemous cartoons. The newspapers and public opinion were split. Was the blasphemer a public martyr for “liberty of the Press, or the right of free speech and free thought”? 1Daily News, March 2, 1883 Or did the cartoons represent a “gross and gratuitous insult to the religious convictions of others”? 2Birmingham Daily Post, March 5, 1883

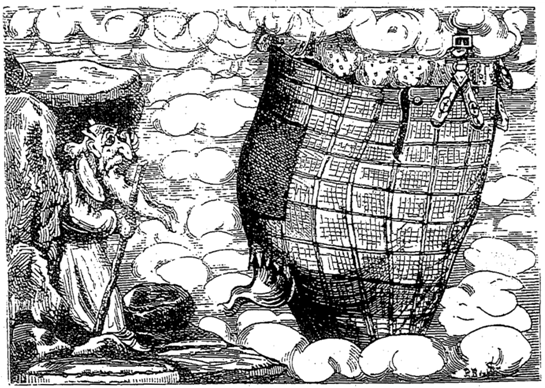

The date was 1882. The cartoons were the “Comic Bible Sketches” published in the Christmas edition of the Freethinker by George Foote. They were based, as it happens, on precedents from a French publication, La Bible amusante. The cartoons look laughably innocent compared to some of the blasphemies that the gods have suffered since. For example, in “Moses Getting a Back View” (right) a bewildered Moses gets to peek at God’s appropriately massive posterior. The cartoon is a pastiche on Exodus 33:23, where Moses asks to see God’s glory and God only allows him see his back. It was not by accident that Foote seized on one of the many moments where God hides himself from representation and institutes a wariness about imaging the divine. For this and other similar images, Foote was indicted and sentenced to a year’s imprisonment with hard labor. In this case, the British courts meted out the physical punishment for pen-crimes.

God’s back, cheekily switched to his backside, is very modest compared to recent images of holy figures with their buttocks exposed (though note the tear in the trousers, and what might be a hint at a little piece of toilet paper). Similarly, Monty Python’s Life of Brian, released in 1979, seems so nice and genteel when compared to the horrendous The Innocence of Muslims, uploaded onto YouTube in 2012. But Life of Brian was not genteel enough for the Bishop of Southwark Mervyn Stockwood and the satirist Malcolm Muggeridge, who in 1979 turned up on the debate show Friday Night, Saturday Morning to lambast John Cleese and Michael Palin. The bishop (flamboyantly Christian in his giant cross and purple robe) addressed Palin and Cleese as fellow Oxbridge boys: he reprimanded them for having betrayed their privilege by failing to abide by rules of courtesy and tone.

The bishop was looking back to the old rules of blasphemy, old rules stretching back to the late seventeenth century—the time of John Locke, the Deists, and the rise of the coffee shop and the expansion of the public press. As Steven Shapin argues, truth was (and is) a matter of credibility, status, etiquette and “epistemological decorum.” The biblical god could be subjected to erudite in-jokes safely confined to the inner circle of learned gentlemen. But gods and state apparatuses were far more sensitive to jokes made in the vernacular, which lowered the social status of holy figures. Thomas Woolston (1668-1733) remained in prison until his death for making some excellent one liners—my favorite being the quip that Jesus’s failure to recognize his mother at the wedding in Cana (‘Woman, what have I to do with thee?’ [John 2:4]) was clear proof that the messiah was drunk. If Woolston had been able to pay the exorbitant fine of 25 pounds per publication he could have got out of jail. (By way of rough comparison, 1 pound equaled 20 shillings; 8 shillings would buy a bottle of champagne in Vauxhall; and 2 shillings 6 pence would get you a whole pig.)

For centuries, we have negotiated a very awkward and much-compromised path between the prohibition and the celebration of freedom of speech and critique. Criticism and freedom of speech are not just to be tolerated: they must be publicly exhibited as proof of the liberal polities to which we aspire. But evolving freedoms of speech and religion have to be managed: freedoms have always been carefully regulated and have never been allowed to run wild.

Censorship and prohibition rapidly became an affair of class and style. Law has struggled, ludicrously, to set out a space for legitimate criticism or “argument[s] used in good faith and conveyed in decent language,” while trying to build a firewall between such critique and its opposite, blasphemy. As a nebulous and highly volatile category, blasphemy can only be pegged out by strange and special adjectives such as “contumelious,” “scurrilous,” “ribald,” “derogatory,” “defamatory,” and “puerile.” As these words clearly show, blasphemy is a social-political drama of respect and respectability. It is a spatial and directional term. “Scurrilous” claims are claims which damage a reputation. The prefix “de-“—meaning “down from”—implies a spatial demotion from high to low.

And “ribald” means bawdy. As Foote’s image of God’s giant bum shows, old style blasphemy was not averse to being a little bit bawdy, indelicate, off color, risqué. But for Foote’s contemporaries, God’s braces and patched checked trousers may have been equally or even more offensive. Here, God is not dressed as a gentleman or a Member of Parliament; in other cartoons he is dressed like a traveler or vagabond. Blasphemy is, similarly, a matter of access, circulation. Foote sold his Freethinker for what he termed the people’s price of one penny in a deliberate inversion of the astronomical fine of 25 pounds—he was doing the very best he could in the media of the 1880s to spread blasphemy-sedition to the working class.

Blasphemy is a ritualized act, with iconic flash points that change over time: today the flashpoint is sex. Foote’s giant divine posterior is completely outflanked, so to speak, by the sexual humiliation of sacred figures that has now become de rigeur. Blasphemers now activate the idea of “blasphemy” by showing holy figures stripped naked, or involved in demeaning sex acts. The homoerotic poem “The Love that Dares to Speak its Name,” written in the 1970s (around the same time as the far more jocular Life of Brian) turns Jesus into a homoerotic lover of men—to the point of necrophilia. These days, the gods long for the days when their worst problems were cheeky presentations of (clothed) butt cheeks, or cheeky accusations about a tipsy messiah.

Rites of blasphemy show what first comes to our minds when we think about freedom. Since the (still very recent) decriminalization of homosexuality and the alleged sexual liberation of the 1960s and 1970s, sexual liberation is what first comes to mind. In the 1880s, for Foote and his contemporaries, the idea of freedom was firmly attached to political freedom—related, for some, to the campaign to be free to be an atheist or, in the recently coined jargon, “secular.” The authorities were threatened by a terrifying array of political freedoms: nascent socialism, communism, and new anarchist movements—as well as mass popular movements for the working class (male) vote. These campaigns had only been partly pacified by the Reform Act (1868), which had enfranchised “respectable” working men (read: an income of 26 shillings a week) while excluding the “residuum.” In other exclusions from the democratic process, public atheists or secularists were not allowed to be members of parliament. As a site of morality and public value and respect, secularism did not exist.

Foote was campaigning for (among other things) the right to be secular. He represented a minority. Minority is not just a matter of numbers, but value; status in relation to social and moral values. Foote wanted to give the newly defined (and for many unbelievable, non-existent) space of the secular value, plausibility, and respect. He wanted to force credence and respectability for the category of non-belief. And there was something audacious and daring about seeking validity andcredibility for the realm defined as the lack of belief. Blasphemy was essential to the substantiation of the secular. Like all public movements that are retrospectively claimed as natural flowerings of democracy—just like, for example, universal suffrage, or the removal of civil disabilities for Jews and Catholics and nonconformists—the secular did not follow naturally from (Christian) democracy, but forced itself, becoming increasingly assured and confident through acts of blasphemy and comedy.In the 1880s, the secular was as implausible and threatening as the prospect of the vote for male laborers or women. Through the insult of blasphemy, the secular was naturalized, so much so that it was assumed to become the default ground beneath our feet.

In Foote’s day the British authorities were deeply fearful of the threat of Home Rule in Ireland and were reeling from the threat of revolution so vividly demonstrated in the Paris Commune of 1871. By importing blasphemous cartoons in the style of La Bible amusante, Foote deliberately provoked fears of revolution flooding across the channel. The same year that Foote was convicted, the Explosives Act was rushed through Parliament. Today the political options seem far more contracted and consensual. We look back at the world that never was and the dreamers and schemers for whom politics was an incendiary affair. Perhaps our freedoms become more vivid for us if we provoke religious fanaticism to re-commit ourselves to our shared value of being free, but the duel between freedom of speech and prohibition or respect for religion is not an old record that can be pulled out and replayed in the same old way, with the same old effects.

Blasphemy does not take place in some timeless context-less space where none of us (not even the gods) get to live. Timing and direction are everything in comedy—and in blasphemy. Foote was a late Victorian addressing and taunting a conservative Christian political establishment. His satire punched upwards, towards the heavens and the courts. Blasphemy once applied to gods, or more accurately gods and governments. It is now widely understood as an offense against religious subjects, rather than an offense against the gods in which not all of us believe. But traditionally, blasphemy has been satire that punches upwards—towards the gods—and then towards those special figures that seem to stand closest to the powers that be.

It can be profoundly unhelpful to use a catchall term like blasphemy that seems so oblivious to space and time—or to repeat vague dichotomies about freedom of religion versus freedom of speech. Surely blasphemy changes when it changes direction: when one is “derogatory” or “defamatory” to a group on the periphery, in the banlieue.3 I don’t mean to flatten the complexity of the suburbs or deny the high social standing of many Muslims in Europe, but the cartoonish, broad brushstrokes convey an important truth, even if they run the danger of caricature. Islam in Europe has but a fragile, nominal equality. Note the bizarre regularity with which European Muslims have been called on to publicly declare themselves against the bloody massacre of journalists and shoppers at a kosher supermarket. In the U.K., the conservative Communities Secretary, Eric Pickles, took the opportunity to write a public letter to Muslim authorities asking them to “explain and demonstrate how faith in Islam can be part of British identity.” No one called on Norwegian Christians to reassure the public that they did not support the mass killings by Anders Behring Breivik in the name of a rogue Christianity—or his rage against women and Islam. While few know much about the details of (any) religion, in Europe, Christianity—the “home” religion—is widely believed to have some kind of foundational value or to be generally in tune with democratic values. Islam has the same kind of standing as Foote’s nascent secularism: irrespective of numbers, it is a “minority” because it lacks credence, credibility, value. Unlike Christianity or today’s secularity, Islam it has no automatic social standing in relation to shared European values, but is widely perceived as standing in a combative relation to those values in the name of Islam.

Why do we keep summoning and provoking religion (but not in the generic sense, never in the generic sense) in our ongoing battle for freedom? Don’t we know what else to ask to the duel? I don’t want to simply echo the point that Joe Sacco makes so deftly in his recent cartoon for The Guardian. My own poor pen can add nothing to this brilliant cartoon. But my own question are: Are these acts of blasphemy strangely comforting, because they suggest that religion—fanatical religion—is the only remaining, or the most important obstacle remaining, between us and the holy grail of being really “free”? Are gods and the god-fearers really where the power is these days? Or are other transcendent, invisible forces afoot, ones in which we all believe? Does focusing on the freedom to damn the religions allow us to forget all the pressures of security and surveillance, copyright and accountability and regulation? Does a fanatical obsession with the fanatical god-fearers help us forget the whistleblowers imprisoned for leaking military secrets; those prosecuted for insulting widely shared values (such as cherished nationalisms); or the force of law that in so many ways regulates our being, our bodies, and our speech? Law really gets around, far more effectively than the old gods ever did. As Andreas Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos puts it: “The city is so thick with law that the law is not perceived.” Law and the economy are not as easy to summon to court or accountability as the gods and religious believers—even though they are more ubiquitous and potent than the gods could ever be. Perhaps we keep summoning and provoking the old religions because we don’t know what to do with these new forms of divinity. Concentration on the fury of the old gods and their supporters at least gives us a target we can see.