When it comes to political theology, everything old is new again. At least that is the impression given by the growing interest in political theology within early modern literary studies—a dynamic relationship between past and present that often blurs our conventional delineations of what is new and what is old. Although political theology is traditionally recognized as a distinct problem of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries—often understood as a stubborn and pervasive entanglement between the philosophical roots of religion and modern statecraft—early modern literary scholars have extended the boundaries of such a dilemma back into the early modern age, demonstrating the historical reach and enduring urgency of the fraught and fecund intersections of theology and political theory. Victoria Kahn’s The Future of Illusion: Political Theology and Early Modern Texts (2013), reviewed here on The Immanent Frame, is only the most recent example in a spate of studies dedicated to questions of political theory, theology, and the literary imagination in early modern England. Such work includes Debora Kuller Shuger’s Political Theologies in Early Modern England (2003), Julia Reinhard Lupton’s Citizen-Saints: Shakespeare and Political Theology (2005), Graham Hammill’s The Mosaic Constitution: Political Theology and Imagination from Machiavelli to Milton (2012), Joseph Jenkins’s Inheritance Law and Political Theology in Shakespeare and Milton (2014), and edited collections by Adrian Streete, Early Modern Drama and the Bible (2012), and Hammill and Lupton, Political Theology and Early Modernity (2012). With fourteen contributors included in the latter collection, the early modernist interest in political theology only seems to be increasing.

When it comes to political theology, everything old is new again. At least that is the impression given by the growing interest in political theology within early modern literary studies—a dynamic relationship between past and present that often blurs our conventional delineations of what is new and what is old. Although political theology is traditionally recognized as a distinct problem of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries—often understood as a stubborn and pervasive entanglement between the philosophical roots of religion and modern statecraft—early modern literary scholars have extended the boundaries of such a dilemma back into the early modern age, demonstrating the historical reach and enduring urgency of the fraught and fecund intersections of theology and political theory. Victoria Kahn’s The Future of Illusion: Political Theology and Early Modern Texts (2013), reviewed here on The Immanent Frame, is only the most recent example in a spate of studies dedicated to questions of political theory, theology, and the literary imagination in early modern England. Such work includes Debora Kuller Shuger’s Political Theologies in Early Modern England (2003), Julia Reinhard Lupton’s Citizen-Saints: Shakespeare and Political Theology (2005), Graham Hammill’s The Mosaic Constitution: Political Theology and Imagination from Machiavelli to Milton (2012), Joseph Jenkins’s Inheritance Law and Political Theology in Shakespeare and Milton (2014), and edited collections by Adrian Streete, Early Modern Drama and the Bible (2012), and Hammill and Lupton, Political Theology and Early Modernity (2012). With fourteen contributors included in the latter collection, the early modernist interest in political theology only seems to be increasing.

Such an outpouring of scholarship on early modernism and political theology raises the question: what does Renaissance London have to do with Athens and Jerusalem—or, as the case may be, twentieth-century Germany? To be fair, political theology is not entirely new to early modern studies. Ernst Kantorowicz’s 1957 study, The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology, has long been regarded as a classic among early modernists. Previous early modern scholars, however, have mined Kantorowicz’s work primarily for its insights into sacred kingship—less interested in its theological content per se than in using such content to translate religion into more comfortable social, economic, and political terms.

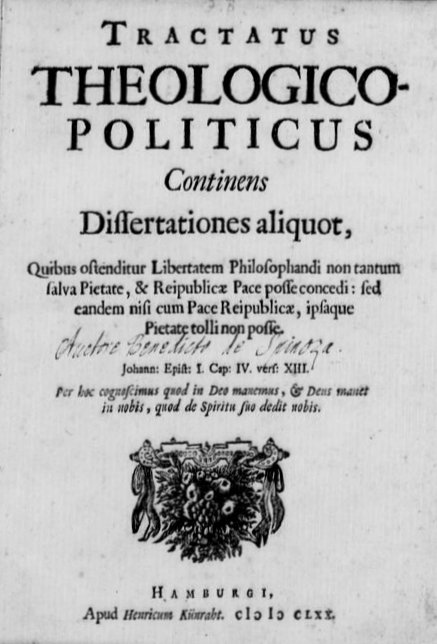

But the subject of political theology has taken on new direction and urgency in the past decade. Recent work takes as its starting point the global political crises and eruptions of the twenty-first century. This scholarship historicizes such crises, tracing these same fissures, gaps, and frictions between religion and politics to the divisive theologico-political environment of post-Reformation England. Nevertheless, such scholars eagerly step outside the chronological boundaries of the Renaissance, engaging twentieth- and twenty-first-century theorists of political theology such as Carl Schmitt, Leo Strauss, Walter Benjamin, Hannah Arendt, and Giorgio Agamben.

This approach to political theology conceives of its enterprise as a “form of questioning that arises precisely when religion is no longer a dominant explanatory or life mode”; such a framework “finds its questions rather in the moments where religion is not working—but neither are the secular solutions designed to replace it.” Accordingly, it is the religiously fractured moment of post-Reformation England—precipitating the wars of religion on the continent; the execution of Catholics, Protestants, and Catholics again; and, later, the overweening divine right of Charles I—that undoes easy alliances between the religious and the political and instead produces the modern problems that plague their relation.

But if these events have always been evident to early modernists, why has political theology become of interest now? What shifts and re-orientations within early modern literary studies have cleared the way for such a focus? It would be natural to see this interest as a corollary to the oft-mentioned religious turn. Certainly the recent openness toward religion in early modern studies has enabled greater attention to the theological component of the political theology dynamic. Yet while some scholars have without hesitation seen their work in political theology as an extension of the turn to religion, others have tried to distance themselves from purely religious approaches. In what feels like an opening salvo, for example, the first sentences of the introduction to Hammill and Lupton’s edited collection declare, with a hint of exasperation: “Let’s get this straight. Political theology is not religion.” That the authors felt this distinction warranted attention in their opening sentence suggests that this newer coterie of scholars is made uncomfortable by a too-easy association with religion; Hammill and Lupton later admit that their political theology seeks to critique the religious turn as much as it draws inspiration from it. No doubt a portion of these scholars seem decidedly more interested in political theory than theology, while Kahn’s book goes so far as to seek an adequate secularism that can supersede religious models altogether. But if the turn to religion did not entirely propel the recent scholarly early modernist interest in political theology, then what other factors are at play?

Perhaps another appeal of the political theology approach emerges from a growing discontent with the field’s dominant framework of historicism. Since the 1980s, the “New Historicism,” inaugurated by Stephen Greenblatt, has been the lingua franca of early modern literary criticism. Such an approach insists on the otherness of the past; scholars working in this vein approach literary texts as shaped by and shapers of a robust yet foreign historical milieu, the recovery of which is crucial to making sense of a culture and its literature. Over the course of three decades, the successes of this approach have been made eminently clear, but other implications have begun to sit uneasily with early modern critics—especially the assumption that literature, ideas, and humanist inquiries can be explained by, and thus reduced to, their participation in a particular and ephemeral historical moment. Such an assumption does little to explain the purchase that authors like William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, and John Milton have had over time and on us today.

In turn, scholars have started to look in many new critical directions, inciting, among other trends, a tenuous “return to theory.” Political theology was one of many such approaches, for example, included in Paul Cefalu and Bryan Reynolds’ edited collection The Return of Theory in Early Modern English Studies (2011). By engaging a chronological range of thinkers extending from St. Paul to Giorgio Agamben, political theology turns away from new historicist assertions of the otherness of the past, insisting instead that the relation of the political to the religious is not simply a local phenomenon; that questions of their relation are enduring and transhistorical; and that the tensions they embody are, as Lupton writes, “born out of historical traumas and debates, but not reducible to them.” While historicism certainly isn’t going anywhere, the interest in political theology indulges a growing critical desire to attend to broader questions of meaning that persist beyond and outside the circumscribed borders of a local environment or period.

In turn, scholars have started to look in many new critical directions, inciting, among other trends, a tenuous “return to theory.” Political theology was one of many such approaches, for example, included in Paul Cefalu and Bryan Reynolds’ edited collection The Return of Theory in Early Modern English Studies (2011). By engaging a chronological range of thinkers extending from St. Paul to Giorgio Agamben, political theology turns away from new historicist assertions of the otherness of the past, insisting instead that the relation of the political to the religious is not simply a local phenomenon; that questions of their relation are enduring and transhistorical; and that the tensions they embody are, as Lupton writes, “born out of historical traumas and debates, but not reducible to them.” While historicism certainly isn’t going anywhere, the interest in political theology indulges a growing critical desire to attend to broader questions of meaning that persist beyond and outside the circumscribed borders of a local environment or period.

Despite this general transcending of chronological boundaries, one troubling implication of the more recent recourse to political theology is its endorsement—sometimes tacit, sometimes explicit—of a categorical “break” separating the early modern period from the Middle Ages. Because this particular brand of political theology takes as its premise that religion is no longer compelling or explanatory, it often seems to assume that the Reformation is the primary font of such a phenomenon, and that political theology was thus an invention, or symptom, of the early modern age.

But, as with other histories of modernity, this formulation implicitly characterizes the Middle Ages as a monolithically Christian, harmonious theocracy and thus unfairly disqualifies it from consideration. Such an assumption was certainly not shared by Kantorowicz, whose historical study reaches deeply into the Middle Ages and characterizes political theology as a “quid pro quo” that “had been going on for many centuries, just as, vice versa, in the early centuries of the Christian era the imperial political terminology and the imperial ceremonial had been adapted to the needs of the Church.” More broadly, such scholars silently consent to the myth that modernity radically springs from the dull, aching head of the premodern past.

Despite this tendency, the pursuit of political theology in early modern literary studies tends to be more oriented toward gathering and including rather than limiting and excluding. Indeed, because this work so deliberately engages the realms of philosophy, theology, and political theory—allowing Shakespeare, Marlowe, and Milton to converse not only with Niccolò Machiavelli, Baruch Spinoza, and Thomas Hobbes but also with Schmitt, Arendt, and Agamben—it recognizes literature as an equal interlocutor with these other realms, a form of thinking unto itself and not simply an illustrative aid for more rigorous disciplines. Work that continues to affirm this truth can only be beneficial for literary studies and the disciplines it interacts with.