As National Research Director for the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Charles Villa-Vicencio was intimately involved in the historic process that followed the collapse of apartheid and paved the way for a new social order. As a theologian, prior to the commission, he had spoken out against the apartheid regime, writing and editing numerous books that helped lead South African Christians out of complacency about their government’s policies. After the commission concluded, he founded the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, in Cape Town, and now advises peacebuilding efforts around the world. His most recent book is Walk with Us and Listen: Political Reconciliation in Africa (Georgetown University Press, 2009). We spoke at the offices of Georgetown University’s Conflict Resolution Program, where Villa-Vicencio serves as a visiting scholar.

As National Research Director for the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Charles Villa-Vicencio was intimately involved in the historic process that followed the collapse of apartheid and paved the way for a new social order. As a theologian, prior to the commission, he had spoken out against the apartheid regime, writing and editing numerous books that helped lead South African Christians out of complacency about their government’s policies. After the commission concluded, he founded the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, in Cape Town, and now advises peacebuilding efforts around the world. His most recent book is Walk with Us and Listen: Political Reconciliation in Africa (Georgetown University Press, 2009). We spoke at the offices of Georgetown University’s Conflict Resolution Program, where Villa-Vicencio serves as a visiting scholar.

This interview was conducted in conjunction with the SSRC’s project on Religion and International Affairs.—ed.

* * *

NS: I’d like to start with your experience with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa. What prepared you for that experience? What kinds of skills did you find yourself using?

CVV: Prior to going to the commission, I taught in a religious studies department at the University of Cape Town. My interest was the impact of religion on secular society and of secular society on religion. I had already worked fairly extensively in the social sciences and political analysis, so the transition was not a very difficult one. It was, in a sense, continuous with what I had done. But it’s interesting that you ask that question. There was a journalist who interviewed me at the conclusion of the commission, and he asked me essentially the same thing. I realized that, though trained as a theologian, I’d hardly used a theological concept for the past three years—but, nevertheless, it may have been the most theological job I’d ever had in my life.

NS: How exactly is that?

CVV: The theology that I was teaching and practicing in the church was always related to building a decent human society, and that’s what we were trying to do in the commission. My feet were deep in liberation theology, contextual theology, and black theology. The jargon of the day was that you don’t write theology or teach theology or read theology—you do theology. The commission’s essentially pragmatic task seemed to me to be also essentially theological.

NS: Since then, have you found yourself drawing again on explicitly theological language and resources? Or do you find that you’re still able to do theology in this more implicit way?

CVV: When my time in the commission ended, I went back to the University of Cape Town, back to the department of religious studies, and realized that my concerns had moved on—whether it was forwards, backwards, sideways, upwards, downwards, I’m not sure. I resigned from the university and set up the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation. Since then, I’ve moved more and more into the area of transitional justice, peacebuilding, human rights, political conflict, and negotiation theory. But, very recently, I have found myself tending to reach into the theological pot again. In the last year or so, probably, I have become more and more conscious of the importance of religion and theology—above all, the importance of spirituality, if one can make that distinction, which I think one can.

NS: Can you say more about that spirituality? What does it mean for you?

CVV: For me, spirituality has to do with having an openness towards life and towards truth. It means wanting to move beyond any closed ideological, dogmatic system. It also means a willingness—and, in fact, a desire—to discover what lies beyond the material. I’ve often said to myself that the question of God and the question of the divine are more important than the answers. It’s a very, very arrogant thing to begin to describe who God is or what the divine is. Yet these questions range from the relationship between religion and the sciences to ethical inquiry, and certainly to political justice, reconciliation, and coexistence. In that sense I regard myself as a very spiritual person. But I find myself resisting institutional forms of religion that try to impose upon me and everyone else a definition of the divine. It’s openness that I think is really important.

NS: Do you think this kind of openness has become more common in South African culture since the end of apartheid?

CVV: It is stronger today than it was five years ago, and different from what it was in the bad old days. During apartheid, the constitution said that South Africa was a Christian country. At the time of our transition, there was a lot of discussion about interreligious dialogue. In the negotiations, we quite easily agreed that South Africa ought to be a secular state—secular in the sense that no religion is prioritized and all religious traditions may come to expression. People’s interest began to turn away from religion, towards politics. The Christian churches are not nearly the social and political force that they were. But now I think we are beginning to see a new openness to the spiritual. If we’re going to learn to live together in this place, we need something else. We need a little fire in the belly. We need something to drive us, to call us, and to persuade us, and that’s what spirituality can do. I’ve even come across fairly serious atheists and agnostics in South Africa who think we need it as well: that openness to transcendence, to the poetic dimension of existence.

NS: Did the institutional Christian churches become identified with the old regime, so that throwing out apartheid meant throwing them out too?

CVV: The answer to that is nuanced. The dominant position of the church—not only the white Dutch Reformed Church, but English-speaking churches as well—was to submit to government. But there was also a church-within-a-church, a group of people who followed the gospel that was calling us out of apartheid. In the old days, you could clearly define that group in terms of initiatives like the Kairos Document and the Balhar Confession. Now, that church-within-a-church—and mosque, and synagogue, and temple—is more difficult to define, but it is there. Just as we sought to be the catalyst for change in the old regime, people now are working for a new society that is accountable and legitimate in terms of the constitution, which is a very fine constitution. How do we get there? It’s going to take more than politics.

NS: You mean it’s going to take spirituality? Is that where the church-within-a-church is heading today?

CVV: Yes.

NS: What about you? Do you continue to consider yourself Christian?

CVV: I think of spirituality as the realization of our identity as true human beings, through the traditions in which we find ourselves. I can’t get out of my skin. I am a Christian in terms of baptism, training, and milieu. In my head, if not in my mouth, I instinctively tend to use theological terms and concepts. Muslims do that in terms of their traditions, and Jews, in theirs. We have to dip into our own wells in order to be inspired and equipped for this quest after true humanity.

NS: Is there something about South African spirituality that is distinct from other forms emerging in other places?

CVV: To begin with, the African worldview—for lack of a better word—is already very spiritual, in that it discerns the presence of the divine in material things, sacred space, ritual, and the ancestors. This spirituality contributed in a very significant way to the South African willingness to accept a negotiated settlement and a truth and reconciliation commission, rather than merely resorting to prosecutions. At its core is the notion of ubuntu—that I am a person through others. I am a person through you, and you are a person through me. If there is enmity between us, you are a lesser person and I am a lesser person. The African tradition rests on that collectivity, that sense of belonging, that sense of community.

NS: What challenges does this kind of spirituality face in the process of reconciliation?

CVV: The good Archbishop Tutu—and I’ve never worked with a more spiritual and decent man in my life—keeps reminding us, forgiveness! He and I differed there a little bit. I think it’s too big a demand to make on anybody, to ask them to forgive—especially people who have suffered, who have been abused, or who have abused. That’s a very deep, personal thing between people, and between people and God. I see reconciliation as far more modest: learning to live together and respect one another. That’s the necessary groundwork, and I think it’s all one can ask for. We’ve got to learn to be reconciled before we can forgive. We don’t have to forgive in order to have peace. We don’t have to forgive in order to have political decency. But we’ve got to reconcile. Though I hope for much more, this is enough. Still, the archbishop insists on forgiveness, and perhaps the definition of reconciliation I use is an inadequate one. Perhaps it’s going to take more. But in the meantime, I’m prepared to settle for that.

NS: What you say makes me wonder whether, perhaps, as a white South African, you may not be in a position to talk about forgiveness in the way Archbishop Tutu can. Do you think your identity has anything to do with your position?

CVV: You make a very good point. One of the most difficult questions that I have continually asked myself in my life, and that I have been haunted by, is what can I, as a white South African, do in what is essentially a black struggle? We say that this is a non-racial struggle, and blacks will often tell us things like, “Who said you’re white?” But I have to be more modest. It’s not for us to forgive, it’s for black folks to forgive. I suppose that has shaped my thinking to an extent.

NS: Earlier you mentioned the 1985 Kairos Document, which got you involved in extended conversations about the role of violence in social transformation. How has your thinking about violence evolved since then?

CVV: I was—and, I think, still am—essentially a believer in just war. The time comes when there seems to be no other way, when nothing else has worked, and you’re dealing with a violent aggressor. I think the resort to arms in South Africa by liberation movements around 1960 was probably correct. They tried everything else. I’m not a pacifist. But as I’ve become more and more involved in working in the African Great Lakes region, and in the Horn, it has made me question any justification that I may ever have given for violence.

NS: Why?

CVV: Because violence runs away with itself. Fighters get caught up in the enthusiasm of the moment and become excessive. I am prepared to grant that there may be a just cause for a war. But as you engage in it, almost by definition, you’re drifting into a situation where the means that you employ are very, very difficult to justify. In the truth commission, for instance, we said that the African National Congress’s resort to arms was a just one. But the means that they employed in certain situations were not just. Can you have a just war that does not degenerate into unjust means? I don’t know. A lot of people will say that you can’t, that it forces you to do some terrible damn things, and that you’ve just got to accept this and move on. But it’s a tough call.

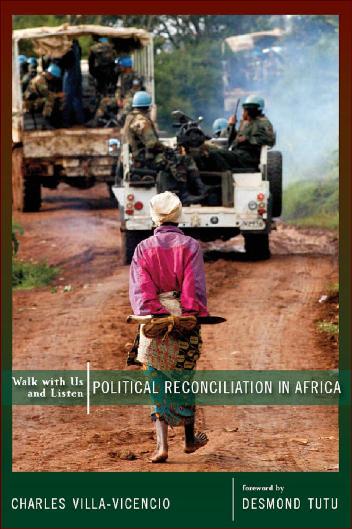

NS: Can you explain the title of your recent book, Walk with Us and Listen?

CVV: The title emerged from my visit to Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, just after the massacre in the early 1980s, which was executed by the North Koreans, at the command of Robert Mugabe. The devastation was just horrible. I was there with a small group of people, and we kept apologizing because we didn’t want to seem like tourists or something. We met a very decent old man man there, and he said, “No. Please come. Walk with us, but don’t tell us what to do. Walk with us—please walk with us—but try and understand. Walk in our shoes for a while before you make suggestions.” It was a conversation that I will carry with me until my dying day. The complexity of Africa! Such terrible, terrible things have happened. Africans are trying so hard to steer a new path. I don’t think the rest of the world ought to go in there with the International Criminal Court, like a cowboy on a horse, intending to sort it out for the natives. We’ve been there before. Just go and stand next to them. Try to show solidarity, and try to understand.

CVV: The title emerged from my visit to Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, just after the massacre in the early 1980s, which was executed by the North Koreans, at the command of Robert Mugabe. The devastation was just horrible. I was there with a small group of people, and we kept apologizing because we didn’t want to seem like tourists or something. We met a very decent old man man there, and he said, “No. Please come. Walk with us, but don’t tell us what to do. Walk with us—please walk with us—but try and understand. Walk in our shoes for a while before you make suggestions.” It was a conversation that I will carry with me until my dying day. The complexity of Africa! Such terrible, terrible things have happened. Africans are trying so hard to steer a new path. I don’t think the rest of the world ought to go in there with the International Criminal Court, like a cowboy on a horse, intending to sort it out for the natives. We’ve been there before. Just go and stand next to them. Try to show solidarity, and try to understand.

NS: Was watching how the ICC operates in Africa what compelled you to write this book?

CVV: Yes, to a large extent. The only indictments that the ICC has had to date are of Africans. Look around the world. Look at Latin America. Look at Colombia. Look at Palestine/Israel. Look at Iraq. Look at Afghanistan. Look at Chechnya, et cetera. There is something wrong. For me, the last straw was in relation to Sudan. The African Union went to the UN Security Council and asked for twelve more months of negotiations before issuing the warrant. The Security Council said no. I understand the desperation of the West regarding Darfur. I also realize that the international community was haunted by its failure to act in Rwanda. I think it was, however, the worst-timed political decision in Africa in recent memory. Just at the point when it was trying to negotiate, the African Union gets told by the ICC to keep out of it, and that the time for talking is over. Yet, as the Sudanese referendum draws nearer, the West now realizes the importance of negotiation to ensure the peaceful implementation of its outcome. You can’t persuade anyone if at the same time you’re holding a gun to their head. There is an African ethic, an ubuntu ethic, that says let’s sit down and talk. I don’t want to romanticize this, because it’s true that some people don’t want to talk, and you can’t talk to someone who doesn’t want to talk. But if someone says that they’re prepared to sit down and negotiate, you don’t put a gun to their head. The decision about Sudan is going to come back to haunt us. Africans perceived it as a new form of colonialism: first came the missionaries, then came the soldiers, and now come the moralists, telling us what to do.

NS: What in particular can the international community learn from traditional African modes of problem-solving, law, and accountability?

CVV: First, bear in mind that what we call “international law” is very often Western law, isn’t it? It’s not a very cosmopolitan or inclusive form of law. It’s not universal. It’s a certain kind of law. I hope this doesn’t sound simplistic, but the West and Africa have got to talk. Whereas Western law has an individualistic ethic—it goes after the individual offender—the African approach emphasizes the communal. I’m not one of those people who says that there must be no prosecutions in Sudan, and if I were to draw up a short list, my guess is that Bashir’s name would have to be on it. But at the same time, we’ve got to recognize that if there’s going to be peace in Sudan, it’s going to take more than prosecutions—and that’s what the African tradition can teach. Besides, the West has got to understand, as it says in the United Nations Charter, the need to work through local agencies to the extent that is possible at a given time.

NS: Say more about what an African response looks like. What kind of practices does it involve?

CVV: It begins with coming together; perpetrators and victims have to look one another in the eye. We’ve got to ask, “Why did we do this? What went wrong?” When we handed the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report to Mr. Mandela in October, 1998—all five volumes—he said there was one chapter that may be more important than any other. It’s only about ten pages. It has to do with the causes, motives, and perspectives of perpetrators. He said that if we don’t understand why people committed these terrible crimes, and if we don’t do something to ensure that what motivated them is addressed, it could happen again. We may call it something different. The color of people may even be different—he said that—but if we don’t go through the long, slow, process of listening, understanding, and trying to put right that which caused these wrongs in the first place, we’re not going to make peace. That’s the African way of doing things. I know it’s messy. I know it’s slow, and it doesn’t have a quick outcome. Some would say it doesn’t have an outcome at all. That is Africa. I’d argue that it’s also Christian.

NS: In that case, to what extent are we talking about two diverging kinds of approach—African and Western—and to what extent a convergence between them?

CVV: I’m talking about that convergence. People in the ICC like to use the word “complementarity.” Can international law complement national law? And can national law complement international law? If we’re going to ensure that international law, the ICC, the Rome Statute, and all that good stuff—and it is good stuff—acquires legitimacy, we’ve got to ensure that Africans, and others in the world who see things differently, are drawn in and allowed to enrich that tradition and ensure that their own traditions are also enriched. That’s where the debate on international law needs to go at the moment, as I understand it. It will take patience. It will take decency. And it will take spirituality.