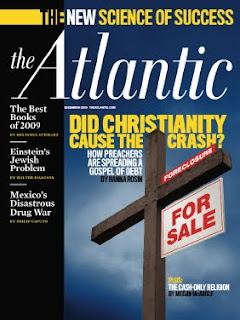

More than a year into one of the worst economic downturns in American history, many minds are still at work connecting the factors that contributed, in one way or another, to the current crisis. In the December 2009 issue of The Atlantic, Hanna Rosin added to the debate over the causes of the crash by casting light on the role played by the prosperity gospel—a strain of Christian teaching tens of millions of believers strong, which proclaims that an unfaltering faith in God will lead to monetary and other material blessings in this lifetime. In the article, Rosin exposes concrete examples of banks teaming up with prosperity preachers to convert believers into subprime loan customers and examines the underlying structures and themes that maintain the prosperity gospel as a plausible theology for many Americans.

More than a year into one of the worst economic downturns in American history, many minds are still at work connecting the factors that contributed, in one way or another, to the current crisis. In the December 2009 issue of The Atlantic, Hanna Rosin added to the debate over the causes of the crash by casting light on the role played by the prosperity gospel—a strain of Christian teaching tens of millions of believers strong, which proclaims that an unfaltering faith in God will lead to monetary and other material blessings in this lifetime. In the article, Rosin exposes concrete examples of banks teaming up with prosperity preachers to convert believers into subprime loan customers and examines the underlying structures and themes that maintain the prosperity gospel as a plausible theology for many Americans.

In light of the questions raised and conclusions put forth in Rosin’s article, we asked several esteemed scholars and journalists: What can we say about the relationship between contemporary Christianity and Americans’ economic attitudes, behaviors, and notions of responsibility? We are pleased to offer their responses below.

Anthea Butler, Associate Professor of Religion, University of Pennsylvania

John B. Cobb, Jr., Professor Emeritus, Claremont School of Theology

William E. Connolly, Krieger-Eisenhower Professor of Political Science, Johns Hopkins University

Harvey Cox, Research Professor of Divinity, Harvard Divinity School

Michele Dillon, Professor of Sociology, University of New Hampshire

Michael S. Horton, J. Gresham Machen Professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics, Westminster Seminary California

D. Stephen Long, Professor of Systematic Theology, Marquette University

Rachel McCleary, Senior Research Fellow, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University

Sarah Posner, Associate Editor, Religion Dispatches

James K.A. Smith, Associate Professor of Philosophy, Calvin College

Mark C. Taylor, Chair of the Department of Religion, Columbia Universiy

Jonathan L. Walton, Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, University of California – Riverside

Diane Winston, Knight Chair in Media and Religion, Annenberg School for Communication, University of Southern California

______

Anthea Butler, Associate Professor of Religion, University of Pennsylvania

Anthea Butler, Associate Professor of Religion, University of Pennsylvania

First, I take issue with “contemporary Christianity” or Christianity being labeled the cause of the Crash. What is lost in this conversation is Christianity—at least the last time I read the New Testament, it was, in part, about caring for the poor, or “the least of them.” This particular “hybrid,” the “prosperity gospel,” is a strand of religious capitalism that has its roots in 19th century thinkers like E.W. Kenyon and 20th century purveyors like Norman Vincent Peale, and Oral Roberts. Placing fiscal responsibility in “prooftexting” of biblical scriptures is par for the course for most Americans who consider themselves biblically literate. Of course, that depends on what the definition of literacy is for the individual, and that is usually measured against the pastor’s teachings, as Rosin’s article shows.

Rosin’s article is flawed at points. Her assertion that “Roberts’s fame had faded by the late 1980s, and prosperity preaching briefly imploded soon after” is just wrong. On the contrary, Prosperity preaching maintained a certain presence. What were Frederick K.C.Price, John Osteen (Joel Osteen’s dad) Kenneth Hagin, and Kenneth and Gloria Copeland doing in the last half of the 1980’s? Twiddling their thumbs?

Much like the foreclosure crisis, the elements of this so called “implosion” have continued to be active within churches in America and around the globe. A useful exercise is to show how the financial market’s optimism and pyramid schemes had their counterparts in these types of churches on a global level. Prosperity is not merely an “American issue” but a global one. The upshot is that whatever American beliefs about responsibility, economics, and fiscal behaviors are, they are trumped by the belief that God is in the business of blessing, not cursing, and praying in the name of Jesus will get you a hundredfold return if you just give 10% or more.

______

John B. Cobb, Jr., Professor Emeritus, Claremont School of Theology

John B. Cobb, Jr., Professor Emeritus, Claremont School of Theology

The Biblical tradition is a two-edged sword.

There is much in the Bible that connects the right relation with God to prosperity, long life, and many descendants. The idea that virtue pays is not a monopoly of the biblical tradition, but it certainly gets support there, and participants in the tradition can exploit such “good news” and have done so. This has paid off for the exploiters especially well in the context of American capitalism. The general idea, so prevalent in our society, that our system rewards intelligence, discipline, and hard work, has been religiously transformed and amplified by the prosperity gospel. No doubt this contributes to the consumerism that in turn makes living beyond one’s means acceptable.

There is another tradition in the Bible that the “prophetic” one, that condemns this idea. In this tradition the reason for faith in God is not that this will lead to personal prosperity but that God loves us despite our unworthiness and calls us to love God and, therefore, the whole of creation. We serve our neighbors not because this is good policy but because our neighbors, and that is everyone, are beloved of God. This message is not popular, and some of the prophets were killed for their pains. Jesus stood in this tradition and died on a cross. He condemned the quest for wealth in no uncertain terms.

Some Christians who condemn the quest for prosperity in this life have emphasized otherworldly rewards for virtue. But Jesus taught that the basileia theou (the “Kingdom,” or “Commonwealth,” of God on earth) is worth our sacrifice whatever happens to us here or beyond). Jesus’s true followers are those who out of love seek the common good here and now.

Many of them do find joy and personal fulfillment in such a life, but they seek first the Commonwealth of God.

______

William E. Connolly, Krieger-Eisenhower Professor of Political Science, Johns Hopkins University

William E. Connolly, Krieger-Eisenhower Professor of Political Science, Johns Hopkins University

An evangelical-neoliberal machine created the recent economic crisis. Launched as early as 1981, upon the election of Reagan and publication of George Gilder’s Wealth and Poverty, this complex set the United States on a destructive and predatory course. The link between the right edge of neoliberalism and a large swath of evangelicals is twofold.

The first link is through complementary beliefs. The right edge of neoliberalism presents the market as a self-balancing mechanism that retains its beauty as long as the state is limited to regulating the money supply, providing defense, punishing crime, and obstructing labor unions and consumer movements. And does evangelicalism? Gilder and other religious marketeers identify more volatility and chanciness in the market than neoliberals do, but they maintain the belief that it is subtended by divine providence. These two sets of beliefs, taken together, license investment adventurism and consumption excess, just as they oppose state efforts to tame both.

This complementarity is intensified by spiritual affinity between the two constituencies. By ‘spirituality’ I mean, roughly, a disposition toward the fundamental contours of human existence as a given constituency itself articulates those terms. You might believe in a God who saves those born again and still be generous to those outside the fold (e.g., Jimmy Carter). Or you may secretly resent that same God and the regime it imposes on its subjects. Alternatively, you could identify a universe with no divinity and either resent or embrace this very condition. Numerous other combinations are possible.

Today, market hubris on the neoliberal right and punitive dispositions on the evangelical right resonate together, with each spirituality folding aspects of the other into itself. Together they have spawned the most deleterious irrationalities of the American economy.

To come to terms with both spirituality and belief in economic life-practices themselves is to glimpse what it will take to forge a counter-movement. Such a counter-assemblage must attract many managers, workers, professionals—theists and nontheists alike. It will demand state regulation of volatile markets, turn back the hubris, recklessness, and punitiveness of the last several decades, and pour care for the future into its investment, savings, and consumption practices.

______

![]() Harvey Cox, Research Professor of Divinity, Harvard Divinity School

Harvey Cox, Research Professor of Divinity, Harvard Divinity School

I am come that they might have life and that they might have it more abundantly.

Jesus, Gospel of John 10:10

Thus the Lord blessed the end of Job’s life more than the beginning: he had fourteen thousand sheep and six thousand camels, a thousand yoke of oxen, and as many she donkeys.

Job 42:12

Biblical faith has nothing against either prosperity or abundance. A bountiful life on earth in addition to eternal salvation has always been integral to the Good News. It is inequality that the Bible condemns, the denial of distributive justice. The reason it is hard for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of God is not that he enjoys worldly goods, but that he enjoys them at the expense of the poor. To the man who had two coats, the exhortation to give one to the poor might move him to share, but to the person who has no coat it states a claim he can legitimately make on someone who has a closetful.

In the Bible, prosperity trumps poverty. The voluntary poverty of St. Francis or of Vincent de Paul was admirable. And it no doubt helped them to understand the bereft people they sought to serve. But both knew quite well that involuntary poverty is ugly and degrading. When it is voluntary, poverty is a choice; but when it is not, it feels like a curse. Can anyone expect a hungry mother of three in a fetid slum of Recife or Lagos to respond to a message about the spiritual benefits of poverty?

Liberation theology famously advocates a “preferential option for the poor,” but the option is to join in the struggle of the disinherited against their impoverishment and to reach out for what is rightly theirs. Neither Joel Osteen nor T.D. Jakes invented the prosperity gospel, but they have gravely distorted it. Still, they are half right. It is vital to tell people that God does not will them to be jobless, lacking health insurance, and unable to make mortgage payments while the banking elites pocket millions of dollars in bonuses. But the mortal sin of these preachers is to teach their people that if they are poor, it is their own fault for not praying or tithing ardently enough.

But to change the rotten system that creates such lopsided injustice something more is needed. The prosperity gospel should take the next step. Only when I see Osteen and Jakes leading demonstrations outside the doors of Goldman Sachs and Citigroup, will I believe that they have gotten hold of the real gospel and not the counterfeit version they now pander. The God of Mary of the Magnificat does send the rich away empty, but the same God fills the hungry with good things. Let us not condemn the yearning for these good things of life, but let us not trivialize what we need to do in order to get them to those who need them.

______

Michele Dillon, Professor of Sociology, University of New Hampshire

Michele Dillon, Professor of Sociology, University of New Hampshire

I personally recoil at the term “prosperity gospel.” Of the many varied ways Christian scripture has been used throughout history to give sacred legitimacy to particular interests and political agendas, the notion that God will reward the faith-filled with material riches has always struck me as particularly pernicious pseudo-theology. The Bible is certainly a document open to many diverse interpretations and there is ambiguity in several of its passages. Yet there is little equivocation in its core message that the good life is not one defined by material acquisition and ostentatious consumption but by purposeful acts motivated by generosity and concern for others.

The Sermon on the Mount is supposed to make Christians focus on loving their neighbor, not their Mercedes Benz. I appreciate, nonetheless, the hold of the prosperity gospel in contemporary American society. Hanna Rosin notes that prosperity gospel churches flourish in Sun Belt states with high levels of home foreclosures. It may be more relevant to note that these states (e.g., Florida and Arizona) also have high levels of migration and population instability. These factors make it harder for individuals to find protective buffers against the many persuasive get-rich-quick sales agents and schemes in contemporary society. In unsettled times, unsettled people are vulnerable to siren calls, however well veiled by prosperity pastors, loan officers, hedge fund managers, or reality television producers.

I don’t think we should see the prosperity gospel as a cause of the recent recession, but one among several elements in our entrepreneurial culture promising salvation through short-term investments and wishful thinking that defer the debts of accountability and responsibility toward others.

______

Michael S. Horton, J. Gresham Machen Professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics, Westminster Seminary California

Michael S. Horton, J. Gresham Machen Professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics, Westminster Seminary California

America is a land of freedom and opportunity—even for scam artists. This Atlantic article refers to Jackson Lears’ observation concerning the two personalities that are part of the American character: the self-made person who has followed the rules and deserves his reward and the more gullible kind of optimist who expects to get lucky. Clearly, America’s prosperity evangelists appeal to the latter, but unlike the article’s author, I think that they actually appeal to both. In both sides of the American personality, there is the assumption that the self is at the center of the world, you get what you want if you know the secrets and follow the principles, and heaven is a credit card swipe away. Of course, there’s a place for God, but it’s a supporting role in my life-movie.

Both the self-made American and the get-lucky American are hostile to any concept of a transcendent God who judges and redeems sinners. Reality is defined not by the God who created it, but by the immediate gratification of the sovereign self. First of all, sin doesn’t even enter the picture—or if it does, it’s just bad things that we do. We all have bad days, but we can pull ourselves up by our own bootstraps if we just have some good advice. And we’re willing to pay for it, if the program works. In a culture of consumerism and psycho-babble, there’s very little sense that everyone has a relationship with God, either as a final judge or as a faithful savior. So Jesus does this cameo in my life-movie, either as a moral example to follow (in the self-made version) or as my personal shopper. Existing as creatures in God’s world, turned against God, yet redeemed from God’s judgment by God himself (in Christ’s life, death, and resurrection), are all beside the point when the question is how I can have my best life now.

Joel Osteen may smile a lot more with his fortune-cookie answers to life, but his books are chalk-full of his own principles for success that, if followed, inevitably yield a better you. It may be easier, according to Osteen and his tribe, but it’s still all about pulling yourself up by your own bootstraps. How is that different from atheism? I’m not sure. At least Feuerbach, Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud were more explicit in their belief that “God” is a projection of our own felt needs, but the prosperity evangelists preach as if these folks were right.

Ever since the publication of Baptist minister (and Temple University founder) Russell Conwell’s Acres of Diamonds in 1890, there has been a royal succession of prosperity evangelists. There was Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking (1952), and his protégé Robert Schuller’s quintessentially American gospel was perhaps best captured in his title, Self Esteem: The New Reformation. More staid in his Protestantism, Schuller was nevertheless happy to merge his possibility message with the Pentecostal prosperity gospel whenever it helped the ratings.

It’s easy to point out the zaniness of the prosperity evangelists. In fact, they defy caricature. Furthermore, their “name it and claim it” message may well have contributed to the materialistic excesses of ridiculous mortgages, get-rich-quick investment schemes, and spending sprees that fueled the boom as well as the bust of the recent economy. But my concern is far more serious. These purveyors of narcissism are misrepresenting God, twisting Bible verses out of context to suit their own self-help philosophy, and bringing eternal as well as temporal tragedy for the people who follow them. God has some pretty strong words in the Old Testament for the “false prophets” who “prophesy the delusions of their own minds as though it were the word of God” (Jeremiah 23). Jesus and his apostles were equally clear about the dangers of preaching a different gospel than the one that was delivered once and for all to the saints. Tetzel, the Dominican friar who sold certificates for time off in purgatory under the pope’s supervision, provoked Martin Luther’s “Ninety-Five Theses.” Hopefully, our churches today will stand up to the peddlers of prosperity in our day.

But for those who don’t believe in God, much less in a world that is created by God, under God’s judgment, and a salvation that comes in Jesus Christ alone, apart from all human striving, I would encourage deeper reflection. I would say, ‘Don’t make the job easier on yourself, dismissing any serious engagement with God’s revelation of himself in Jesus Christ by focusing on false prophets (and profits, as the case may be). God has set a date for the trial of every person and has given proof of this by raising Jesus from the dead. If you haven’t examined these claims, you haven’t really examined Christianity’.

______

D. Stephen Long, Professor of Systematic Theology, Marquette University

D. Stephen Long, Professor of Systematic Theology, Marquette University

“Did Christianity Cause the Crash?” Unfortunately, “Christianity” no longer bears sufficient commonalty among its adherents for it to bear the kind of agency suggested in this provocative title. Nonetheless, Rosin admirably discloses the negative social consequences of a Christian heresy—the gospel of prosperity. Christianity’s fragmentation means those primarily responsible for teaching it, such as Joel Osteen, cannot be (non-violently) silenced. That makes it all the more dangerous for it appears to represent ‘Christianity.’ Heresy is not a thoroughly corrupt form of Christianity, but the distortion of a truth. God does seek the plight of the poor to be alleviated. But the gospel of prosperity distorts this teaching, bringing it into alliance with a heretical doctrine of providence where God’s providence no longer works by holding goods in common, but as Adam Smith taught, by each looking only to his own interest. That supposedly brings Isaiah’s “Wealth of Nations.” Only freedom from any common regulation—moral, theological, political—will bring wealth. But this is not a shift in an “American doctrine of providence.” It is its fruit.

Despite showing us the negative social consequences of heresy, I nonetheless think Rosin confuses symptom with cause. A subclass that cleans toilets, picks vegetables and manicures lawns, sought a quick fix to economic servitude. Who could blame them? But the cause lies deeper than the gospel of prosperity. She rightly diagnoses a contributing, theological factor in ‘providence,’ but mis-locates it. For that reason, the question of causes needs expansion. I would suggest the following:

Did Adam Smith cause the crash when he taught his distorted doctrine of providence that seeking to advance the common good did more harm than seeking one’s own interest?

Did Reformed Christianity cause the crash when it adopted this doctrine of providence?

Did the social sciences, especially economists, cause the crash when some drew on that doctrine of providence, and assumed they now had law-like rules of predictive power about future wealth?

______

Rachel McCleary, Senior Research Fellow, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University

Rachel McCleary, Senior Research Fellow, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University

According to John Calvin, a believer’s actions in the world originate in God’s grace and this faith, in turn, justifies itself by the moral quality of the action. The quality of the action, Christian conduct, was defined by a rational system of morality and became the standard by which to measure the glory of God. Thus salvation by work—daily work, not ascetic activities—was organized and rationally justified in an impartial moral system that applied to the activities of one’s daily life and logically led to the rational organization of labor. If this Christian conduct (productivity) was the evidence of grace, then its results (accumulation of wealth) were likewise signs of grace.

Future socio-economic changes brought by Calvinism and spin-off sects resulted in modern capitalism, a “devotion to money”, that has created an acquisitive life style that no longer retains any of the former religious, normative, and motivational factors. According to Max Weber, “Modern capitalism has become dominant and has become emancipated from its old supports.” The linking of a positive attitude toward the accumulation of wealth with certain religious norms regarding individual behavior produced modern capitalism. Over time, the religious aspects no longer served as the reason why people worked long hours; rather, it was simply the acquisition of wealth that motivated people to work hard.

Are prosperity churches in the United States growing because people want to hear a version of the prosperity gospel? Certainly, there is a demand for these types of churches. But, on the supply side, what religious goods are other denominations providing? The relationship between hard work and wealth accumulation is one of the values promoted by various forms of Protestantism. The nonconformist religions, such as Methodism and the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), were integral to the success of the British Industrial Revolution. Nonconformist groups took advantage of existing technological networks (railroads, steamships, telegraph) in ways not previously done by mainstream groups. Nonconformist groups also kept transaction costs down, due to non-economic network advantages among members of their religions. Religious education was important in the economic performance of nonconformist members. Attendance at certain elite religion-affiliated schools translated into learning the values of hard work, self-reliance, and the importance of education to succeeding in life. And enduring social networks developed among those who attended religion-affiliated schools. Religion contributed to economic prosperity rather than religion being the result of it. The prosperity gospel in the United States might lead to new innovations and inventions that will further our economic growth. Then, again is prosperity gospel the result of economic prosperity gone bust?

______

Sarah Posner, Associate Editor, Religion Dispatches

Sarah Posner, Associate Editor, Religion Dispatches

The prosperity gospel is a lot older than derivatives, credit default swaps, and other byzantine Wall Street “products” that leveled the financial markets. Moreover, the fact that humans—not God—dreamed up these contrivances doesn’t poke holes in the prosperity gospel at all, at least from its adherents’ vantage point. If you believe and sow your seed, God will reward you, even as the secular Masters of the Universe greedily orchestrate a global economic collapse.

Surely the prosperity gospel plays a role in persuading its followers to buy into risky financial schemes, including sub-prime mortgages. (You might not be able to afford this thing, but if you have faith and tithe, your mortgage payments will miraculously appear in your checking account.) But to argue that the prosperity gospel, no matter how prevalent it is in America’s mega-churches, brought enough sub-prime borrowers to the table that it “caused the crash” overlooks how our secular institutions can be just as faith-based as prosperity churches.

In other words: Wall Street titans were banking on little more than a wing and a prayer, too. It’s the American way.

That’s not to say that prosperity hucksters aren’t just as driven by avarice as the bankstas; just because they puff up their claims with Scripture instead of spreadsheets doesn’t make them any less complicit in leading the gullible on a path to financial ruin.

And that’s also not to say that prosperity hucksters would not have found another way to squeeze blood out of the turnip that is many of their followers’ nest eggs, had they not convinced them that God would make sure they could make the balloon payments. The annals of investigative journalism are filled with the sad tales of personal financial crashes because—prosperity hucksters would claim—victims didn’t have enough faith.

The hucksters may not be the sole cause of this crash, but they’re surely responsible for plenty of personal crashes long before sub-prime mortgage brokers began preaching their own kind of prosperity gospel.

______

James K.A. Smith, Associate Professor of Philosophy, Calvin College

James K.A. Smith, Associate Professor of Philosophy, Calvin College

I think Rosin probably oversells the influence of the “prosperity gospel” as proclaimed by the likes of Osteen. As she rightly notes, in fact, mainstream evangelicals (and even mainstream Pentecostals, I might add) have been critical of the “health & wealth” gospel as an aberration.

So prosperity preachers are easy targets for blame—and they certainly deserve that. But what about the sort of low-grade, soft-sell gospel of prosperity that is part of “mainstream” evangelicalism? While folks like Rick Warren are quick to denounce the heresy of treating God like a cosmic bubble-gum machine, run-of-the-mill suburban evangelicals are complicit with a consumerism and fixation on property that operates under-the-radar, as it were. While mainstream megapastors aren’t promising Bentleys for faith, they generally extol a vision of the “good life” that has 4 bedrooms and a 3-car garage, with an SUV in the drive. (If you really want to know what evangelicals value, stroll the parking lot at Saddleback Church—and then ask folks where they live.) This is why evangelicals have been so easily assimilated to the American ideal of economic growth and personal prosperity (an American gospel that is certainly not just the property of Republicans).

In other words, while Osteen and his ilk might be denounced by evangelicals, I do wonder if his gospel of prosperity differs by degree, rather than in kind.

But I would add one other complication to the mix: It seems to me that there is something right about the prosperity gospel. There is a germ of truth to it insofar as the prosperity gospel (rightly!) suggests that the gospel is good news not just for souls, but for bodies—that Jesus came to announce good news not just for the poor “in spirit,” but for the poor. Redemption is also economic.

______

Mark C. Taylor, Chair of the Department of Religion, Columbia University

Mark C. Taylor, Chair of the Department of Religion, Columbia University

Hanna Rosin’s recent cover story in The Atlantic, “Did Christianity Cause the Crash?” is not wrong, but it is superficial and, as such, is symptomatic of the inadequate understanding of religion that characterizes so much public debate. The so-called prosperity gospel has a long history of close ties with leading figures in the business and financial communities. To suggest that its latest version was a cause, rather than a symptom, of the current financial crisis is ludicrous.

The relationship between Christianity—more specifically, Protestantism—and today’s finance capitalism is much deeper and more insidious than people realize. Max Weber’s analysis of Protestantism and capitalism has become canonical, but even this account cannot explain what is going on. As I have argued at length in my book Confidence Games: Money and Markets in a World Without Redemption, the form of capitalism that has emerged since the early 1970s is the product of the intersection of three factors, all of which have a long and complicated history: neo-conservative politics, neo-liberal economics, and neo-foundational religion.

To glimpse how the interrelation of these trajectories has evolved, consider the all-too-familiar term “the invisible hand.” Though rarely recognized, the relation between the divine and the human lies at the heart of the modern understanding of markets. Calvinism not only prepared the way for a flourishing economy but also provided principles for understanding and justifying market activity. The first person to use the image of the invisible hand was not Adam Smith, but John Calvin. For Calvin, God’s providence is the invisible hand that sustains the order of the world even when it is not immediately evident. Smith, who was, of course, from Protestant Scotland, appropriated Calvin’s doctrine of providence to explain the machinations of the market. Emphasizing the aesthetic aspects of Calvin’s theology that were important for Scottish philosophers in the eighteenth century, Smith brought together religion, art, and economics to form the modern theory of markets. Just as the beautiful work of art is characterized by the harmonious interrelation of parts, so the market functions as an integrated system in which individuals pursuing their own interests also promote the good of the whole. With Smith’s translation of theology and aesthetics into economics, the source of order shifted from an external agent—i.e., God—to internal relations among individual human actors. From this point of view, the market is a self-organizing system that regulates itself. F. A. Hayek has gone so far as to claim that for Smith the market is, in effect, a cybernetic system that operates by processing information. The market, in other words, works like a computer.

By the seventeenth century, the Amsterdam stock exchange had already become a thriving speculative market where investors were using financial instruments remarkably similar to the sophisticated products promoted during the 1980s and 1990s in New Amsterdam, i.e., New York. The fundamental belief of latter day heirs to Dutch Protestants is that the market is omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent. For neo-liberals and neo-conservatives, the market is God and God always knows what is best for mere mortals who only mess things up when they intervene in the market’s providential operation.

______

Jonathan L. Walton, Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, University of California – Riverside

Jonathan L. Walton, Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, University of California – Riverside

In September of 2008, I suggested that there was a relationship between the economic excesses of the past few decades and the prosperity gospel. Testimonies from first time homebuyers with questionable credit were commonly deployed to justify the efficacy of health and wealth theology. And luxury goods such as mansions, expensive cars and custom made clothes are often modeled as sacramental symbols of consumerist informed Christianity.

Soon I was inundated with media inquiries. Many wanted to run with this notion that we should lay the blame for the subprime mortgage mess or economic crash at the feet of Christian preachers. But this was never my point. I find it absurd to believe that prosperity preachers have either the influence or intelligence to enact a global economic downturn. The difference, it seems, is whether we interpret the relationship as causal or corollary.

To assert the relationship as causal, as several articles have, grants way too much credit to a motley crew of preachers while shifting our attention away from destructive governmental deregulatory policies and the pernicious speculatory financial practices of Wall Street. The financial sophistication of most of the prosperity preachers still remains at the level of how to collect more crumbled dollar bills in the bucket on Sunday. And, like most Americans, I am pretty sure Kenneth Copeland and Creflo Dollar have little understanding of a derivative bubble or the implications of repealing the Glass Steagall Act.

Yet a corollary connection situates the prosperity gospel among other culture industries that cultivated the conditions for Wall Street’s machinations. Regarding a culture of excessive debt and consumerist indulgence, is the prosperity gospel anymore damaging than MTV’s Cribs? Or A&E and HGTV’s seductive lineup of Flip this House, House Hunters, or I Want that Kitchen? I think not.

It seems there is plenty of blame to go around here. And I would prefer to start at the top and not the bottom.

______

Diane Winston, Knight Chair in Religion and Media, Annenberg School for Communication, University of Southern California

Diane Winston, Knight Chair in Religion and Media, Annenberg School for Communication, University of Southern California

Hanna Rosin’s article on the intersection of the prosperity gospel and the financial crash has all the hallmarks of good journalism. The prose is supple, the reporting in-depth, and the angle—wacky Christians doing stupid things—is appropriately sensational. It’s also another instance of the press’s predilection for extreme examples of God and Mammon, ranging from the Prophet Matthias to Rod Parsley. But why don’t equally current and controversial examples of faith-based stewardship and responsibility make headlines?

A coalition of churches in One-LA lobbies recalcitrant banks to keep people in their homes. Sister Robbie Pentecost engages environmental and economic issues spawned by Appalachian coal-mining. Sojourners produces a timely guide to Biblical responses to the financial crisis. All could open to colorful storytelling but none are likely to make the Atlantic, New York Times or 60 Minutes.

I used to think that “religious folks doing good” wasn’t newsworthy. Then I decided there was an “ick” factor that made do-gooder stories the news equivalent of spinach or castor oil. Now I wonder if there’s a more insidious agenda to circumscribe discussions of religion and economic responsibility. Better to talk about the excesses of consumer capitalism than acknowledge alternative religious, political, and economic visions.

The fact is that all three have been entwined since the beginning of the American experiment. Almost four centuries after John Winthrop’s evocation of “a city on a hill,” pundits and politicians still borrow his words to remind us of our providential calling. But many in Winthrop’s shipboard audience were as concerned with doing well as doing good when the Arabella reached the New World.

Winthrop’s charge was to establish a Christian society that bound citizens to serve God, care for one another and pursue monetary rewards; in recent years, media attention has focused on the prosperity gospel as the modern bastardization of that formula. But there are other examples, ones that Winthrop might better recognize, well worth exploring.

Where to begin…? John Calvin and his slightly older contemporary Martin Luther formed part of a growing movement of minorities that suffered persecution and death, and unless we can think like minorities, or post-Constantinian Christians, I think we’ll miss something of Rosin’s insight.

The Cross and Resurrection for early congregations prior to Constantine and for break away churches from Rome (Cathares, Waldensians, Hussites) during the high middle ages in Europe, are looking at faith not so much from a triumphalist point of view of individual self-interest as from a communal rationale to justify their departure from the Church. Christianity, proper, begins where the Church leaves off. (I’m spinning Troeltsch here). Wealth, class and power had been attributed to Rome and to the King(s) at the top of the food chain, with little differentiation. But with the Reformers, wealth, power and faith were severed and “ethicized” separately. In the USA, they are once again joined at the hip. A Tom Cruise who practices scientology is not much different from a Rick Warren who practices Christianity. Both live a purpose driven life and are rewarded accordingly. Self-help, self-fulfillment, self everything is given a divine mandate. Very little difference, if any, between personal salvation guaranteed by indulgences at any price and personal fulfillment guaranteed by greed, also at any price. But I think that this iconography of the self bears the hallmark of an imperial frame of mind, which can mask the narcissism underneath: only me and, if possible, thee, too, sort of. Persons from minorities would never stoop so low as to think themselves so high. The risks are too great. Deborah and her peasants fought with pitchforks, while Yahweh led the starry hosts. So, yes, basically, I agree with Rosin but with this proviso: Providing the Christian concerned has not been rooted or grown up in a historical context of persecution and danger, then her point holds.

The prosperity gospel enabled its adherents to look with admiration (read: covetousness) on those in their midst who were ‘making it.’ They did not (do not) begrudge the extravagant lifestyles of Benny Hinn, Kenneth Copeland, et.al.; indeed, they would go to the mat defending them, as they have come to equate stuff with faith.

That is one of the legacies of Oral Roberts which seems to be being politely ignored since his death. Offerings to ministry are “pressed down, shaken, running over” and then returned to the giver in the theology of seed-faith offerings. No doubt, others before Roberts had discovered the inherent money-raising charm of that formula, but Roberts skillfully put it to work in the new mission fields of television. His legacy, in my humble opinion, and in King James English, stinketh. It permeates all of television Christianity and has been exported around the world. What will it reap, I wonder, in South America, when the millions there who are buying into it realize the pie simply is not, cannot be, large enough to prosper them all?

As a child of the prosperity gospel (I grew up watching Oral Roberts, listening to Kenneth Hagin and Kenneth Copeland) I find Harvey Cox’s response the most insightful. The fact that he has written on Pentecostalism from a sympathetic viewpoint comes through. The prosperity gospel was born among people who knew poverty and knew that it wasn’t good. Oral Roberts knew it first hand. He understood that deprivation is no fun. The same goes for people like Kenneth Hagin. These guys caught hold of a basic truth that many Christians want to ignore. Jesus did teach about the power of faith in connecting with God to meet this-worldly needs. As much as liberal and conservative Christians want to ignore these verses the fact is they are there. The original purveyors of the prosperity gospel are Jesus and Paul. You simply can’t get rid of their radical statements about the power of God released in a person’s life through faith and through giving.

It is true that much prosperity preaching misuses and distorts these passages, but the fact is most other Christians aren’t preaching and teaching on them at all! They bear much of the blame for purveying their own distorted gospel that omits this aspect of the New Testament’s teaching and thereby causing a great void—a void that begs to be filled. These verses simply won’t go away.

There is a truth to the Pentecostal claim that much of Protestant Christianity is a dead rationalism that fails to do justice to the spiritual aspect of Scripture, the truths of spiritual reality taught in Scripture that have an impact upon the material world.

All this to say, while there is much that is true in the criticism of your respondents, there is also much that they miss, and as long as the truth in prosperity gospel is not acknowledged the more extreme, distorted preachers will continue to fill the void.

Let’s be careful about this. Walton’s empirical work among Black clergy and the Prosperity Gospel movement sets a solid example of how to tether this question of Christianity’s responsibility for the Crash to specific communities. Woolier generalizations are more likely simply to redeploy our own political biases.

Put otherwise, if Christianity can be said to have caused the Crash, can it also be said to have caused the Stimulus???—a notably, in part, magnanimous effort of altruistic social responsibility, no matter how underfunded, or misdirected to bailing out big money it might initially have been. And, then what do we say about the pre-Appalachian Trail refusal of Gov. Mark Sanford to accept any Stimulus money, his conspicuous Carolinian Christian piety notwithstanding? Head hurting yet?

I’ll ignore any theological discussion of the Prosperity Gospel, since it has been well argued above. But from a purely practical standpoint, if churches preaching that gospel did effectively encourage people to buy houses they could not afford, then certainly one could say that Christianity had some impact on the crash. But to measure that impact, let alone use the word “cause,” Rosin should have gone further. She could have tried to quantify how many churches preach the Prosperity Gospel, and how many parishioners they have. She could have correlated location of those churches with foreclosures. She could have found more than one (and I’m sure there are plenty) conflicted minister/loan officer. Without that work, all the article gives us are interesting hints, and buzz-creating extrapolations, rather than any substantive answer to the question her headline asks.

Some interesting points in both the article and the comments. First, there is absolutely nothing biblical about the Prosperity Gospel. One does not claim true Christianity in order to live their best life now or what materialistic items they can accumulate. If the crash was due to false converts claiming to be Christian and seeking material wealth, let’s make sure we distinguish between apples and oranges here. True Christianity teaches contentment not grab what you can now. The Prosperity Gospel is partly responsible for a crash. The crash of the True Gospel being shared and a collapse of morals.