In signature style, Sam Moyn is poised to launch another spectacular provocation with his forthcoming Christian Human Rights. Building on The Last Utopia and a series of article-length projects, Moyn argues that in the 1930s and 1940s, human rights emerged as a religious, conservative, response to the crisis of Nazi-Fascism. On Moyn’s reading, the European Christian right, not the secular left, was the foremost champion of human rights just before and after World War II. However, appeals to human rights did not emerge from philosophical or theological developments long-in-the-making, much less a sudden awakening to the horrors of the Holocaust. Neither did it signal a Christian embrace of liberalism or the legacy of the French Revolution. Instead, human rights represented a way for conservative Christians to promote a narrow, self-serving, agenda: one that sought to protect the special place of Christianity in Western Europe by whitewashing Christian associations with the recent Nazi-Fascist past.

In signature style, Sam Moyn is poised to launch another spectacular provocation with his forthcoming Christian Human Rights. Building on The Last Utopia and a series of article-length projects, Moyn argues that in the 1930s and 1940s, human rights emerged as a religious, conservative, response to the crisis of Nazi-Fascism. On Moyn’s reading, the European Christian right, not the secular left, was the foremost champion of human rights just before and after World War II. However, appeals to human rights did not emerge from philosophical or theological developments long-in-the-making, much less a sudden awakening to the horrors of the Holocaust. Neither did it signal a Christian embrace of liberalism or the legacy of the French Revolution. Instead, human rights represented a way for conservative Christians to promote a narrow, self-serving, agenda: one that sought to protect the special place of Christianity in Western Europe by whitewashing Christian associations with the recent Nazi-Fascist past.

Moyn is right on many, but not all, counts. He is right in putting Christians at the center, rather than the margins, of the human rights story of the 1930s and 1940s. He is right to emphasize that the embrace of human rights did not necessarily amount to a renunciation of the (Catholic) counter-revolutionary tradition. And he is right that Christian human rights are best understood in the “transwar” perspective, as an attempt to use new words to stake out a position in Europe’s thirty-year civil war.

However, new archival findings and recent scholarship indicate that three aspects of Moyn’s account may be in need of revision. In what follows, I’d like to suggest that human rights emerged in a trans-Atlantic space of operation, and that in certain circles they represented a (counterintuitive) response to the rise of anti-Semitism. Further, Christian human rights resulted from an internal, lay-clerical battle, over the soul of Catholicism.

First, while it’s true that Europeans played a critical role in amplifying human rights debates, they did not act alone. In fact, Christian human rights emerged from a solidly trans-Atlantic space of exchange. Many of the most influential Catholics bandying the term “human rights” in this period were North American clerics and laypeople with strong ties to Europe. Consider Father Joseph-Henri Ledit, the Canadian Jesuit based in Vatican City who led the Vatican’s anti-communist crusade and drafted large segments of Divini Redemptoris, the 1937 papal encyclical exploring communism’s violation of (Catholic) human rights. Or take Father John LaFarge, the Rhode Island-born Jesuit tasked by Pope Pius XI with drafting an anti-racist encyclical—a text that never saw the light of day, but that explicitly referenced the human rights of Jews. The list goes on. From the radio broadcasts of the Midwesterner Father Charles E. Coughlin, to the journalistic interventions of East coast activists like Emmanuel Chapman, Dorothy Day, and numerous European Catholic émigrés, Christian human rights emerged as a North American commodity, not just—or even primarily—as a European export.

Second, it is not quite right to say that the history of Christian human rights has nothing to do with the legacy (and worrisome implications) of Catholic anti-Semitism. The archival record indicates that in the late 1930s and early 1940s, key Catholic groups turned toward human rights as a way to calm Catholic clergy worried by the unsettling potential of these groups’ philo-Semitic activism. Christian human rights, at this juncture, became a way to refocus attention on Catholic suffering and Catholic persecution, rather than on matters Jewish. Thus, Christian human rights did emerge in the context of a lay Catholic attempt to wrestle with anti-Jewish sentiment in Europe and North America—but the human rights swerve was also a move away from a full Catholic reckoning with the ramping up of Jewish persecution, and the responsibility of Christians therein.

Third, Moyn’s work skirts the crucial question of lay-clerical and Catholic-Protestant relations. Which groups within the wide and undifferentiated world of European Christendom were most responsible for claiming the mantle of human rights, and for emphasizing their Christian nature? Moyn does a tremendous service in turning scholarly attention to the little-studied Irish constitution of 1937, to papal mention of human rights (in 1937, 1938, 1941, 1942, and 1944), and to an incipient Protestant interest in human rights, as propounded by the German-Lutheran historian Gerhard Ritter after World War II. But one is left wondering: How did Protestant groups respond to and reappropriate Catholic formulations of human rights, and vice versa? Given the great mutual suspicions characterizing Protestant-Catholic encounters (only barely papered over by the emerging “Judeo-Christian” mythos), it seems surprising that these groups meant the same thing when they referenced human rights. Moyn also spends little ink on lay-clerical interactions, and does not address the question of whether it was lay or clerical groups that determined the emergence and success of Christian human rights.

As it turns out, in Catholic circles, laying claim to human rights was not only about asserting Catholic influence in a changing world; it was also a critical move in the struggle for the soul of Catholicism. Two camps squared off. Certain trans-Atlantic Catholics picked up the term in the late 1930s as shorthand for the Catholic embrace of democracy and American political culture. These Catholics, many of whom were Jewish converts, were focused on excoriating Catholic racism and anti-Semitism, without renouncing the core Catholic missionary commitment of bringing misguided souls (including Jews) to “the one true faith.” This not-so-radical (by our standards) conception clashed with one defended by figures such as Pope Pius XII, among others. For Pope Pius XII, the phrase human rights represented a way to celebrate the Catholic “third way”—and constrain liberal-leaning Catholics by pulling the rug from under their feet. For the Pope, human rights signaled the Romanization of Catholicism (not its Americanization), as well as the strong support for “neutrality” in World War II. In the context of 1939-1944, this meant the decision to not take a strong position on Nazi-Fascism.

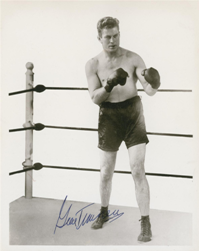

Now for a brief illustrative story on the complexities of the Catholic human rights swerve. In May of 1939, a high-profile group of American Catholics came together in New York to form the Committee of Catholics to Fight Anti-Semitism. The group contained an all-star line-up of American Catholics, from well-known professors to politicians, from acclaimed fiction writers to sports stars (including the all-American boxer, Gene Tunney, pictured above). The group received extensive coverage by both the national and local press.

The Committee was led by the Chicago-born Emmanuel Chapman, a Jewish convert to Catholicism who attended the Jacques Maritain salon in Paris in the late 1920s, studied at that great mecca of interwar trans-Atlantic Catholicism, the Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies in Toronto, and went on to teach philosophy at Notre Dame and Fordham, the leading centers of Catholic higher education in the United States. Under Chapman’s guidance, the group sought to fight the scourge of Catholic anti-Semitism through pamphlets, magazines, and grassroots activism. But twists and turns lay ahead: in a matter of months—by late summer of 1939—the group rebranded itself as the Committee of Catholics for Human Rights. And by 1940, the organization had already dissolved. It would be reconstituted only, under much-different guise, in 1944.

The story of the short-lived Committee is instructive in three respects. First, it demonstrates that there was an intimate (but hardly teleological) link between Catholic anti-Semitic activism and the novel push for human rights. Second, the Committee sheds light on the contingent and dialectical nature of the Catholic human rights swerve. Third, the story illustrates the untidy intermingling of lay and clerical priorities in the making of Christian human rights.

Between May and August of 1939, the Committee was centrally concerned with the problem of Catholic anti-Semitism. In its earliest press release, the Committee declared that it would redress the fact that “Catholics have been deceived into taking part in the [anti-Semitic] campaign of hate.” In its early publications, the group decried Catholic anti-Semitism as undemocratic and un-American. Taking aim at Father Coughlin’s Christian Front as a Nazi façade, the Committee spoke out against the wave of anti-Semitic street violence sweeping New York in spring of 1939. Father LaFarge, whose draft encyclical on Catholic racism and anti-Semitism had just been buried by Pius XII and the Jesuit Superior-General Wlodimir Ledóchowksi, quickly joined the effort. At this critical juncture, presenting Catholicism as anti-racist and philo-Semitic must have represented a personal and professional vindication for the American Jesuit.

In August 1939, the Committee’s executive board announced a name change: henceforth, they would be known as the Committee of Catholics for Human Rights. The rebranding was more than just cosmetic; it signaled a change of focus, too. As announced in a press release, the organization would now dedicate itself to “meet[ing] the growing problems of Catholics in our modern society.” Alongside its continued focus on Catholic anti-Semitism, the group would also attend to the (mis)treatment of Catholics, at home and abroad. “Anti-Semitism is but one facet of the new barbarism which includes anti-Catholicism,” the Committee’s mouthpiece, The Voice for Human Rights, explained.1“Anti-Catholic Bigots in U.S.,” The Voice for Human Rights 1,3 (November 1939), p.2. “Scratch an anti-Semitic propagandist and like as not you’ll find an anti-Catholic.”2“Change of Name Shows Broader Application of Principles,”The Voice for Human Rights 1, 2 (September 1939), p.10. Shortly thereafter, the Committee launched a survey on local “racial and religious bigotry” to measure the extent of anti-Catholic sentiment in the United States.3“Survey of Bigotry in Nation is Begun,” New York Times (August 19, 1940), p.17; “Anti-Catholic Trends Surveyed,” The Voice for Human Rights 2, 1 (August 1940), p.1. Almost exactly two months before Germany began deporting Austrian and Czech Jews to Poland, this Catholic group of trans-Atlantic border-crossers donned universalist, “human rights,” clothes. But what the Committee was really signaling was a turn inwards: the curbing of philo-Semitic activism, and the foregrounding of Catholic persecution.

So in late summer of 1939, the Catholic human rights gambit was not a bold step forward. Instead, it was an exercise in caution, likely motivated by the attempt to steer clear of the looming threat of clerical rebuke. In May 1939, the Committee had risen to prominence thanks, not least, to its ties with the Catholic hierarchy in New York and New Jersey. But in mid-1939 to early-1940, the Committee was rocked by a series of scandals and court cases that identified the group’s members as outspoken anti-Fascists and potential crypto-communists. The scandals led to the full withdrawal of clerical support in 1940. Further, the accusations cost the group’s leading member his job; in 1942, Emanuel Chapman was forced to step down from his professorship at Fordham University. As Fordham’s President, the Jesuit Father Gannon, later commented, over and above the accusations of crypto-communism, Chapman’s “activities on behalf of Jews in America [had] been a source of annoyance and embarrassment.”4Robert I. Gannon to Marie M. Ballem, February 16, 1940, Robert I. Gannon personal files, box 10, folder 25, Fordham University Archives, New York. As quoted by Charles Gallagher, S.J., “Promise Unfulfilled? A First Look at the Committee of Catholics for Human Rights,” in Religion and Human Rights, ed. Devin Pendas (Oxford University Press, forthcoming).

The Committee of Catholics is instructive for a second reason, too. The group’s decision to foreground its Catholic character suggests that already by the late 1930s, an alliance of trans-Atlantic border-crossers had a stake in labeling “human rights” as a specifically Catholic project. In other words, well before Pope Pius XII’s endorsements of human rights in the early 1940s—and almost a decade prior to the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948—the liberal tradition of rights was being reformulated by a motley group of Catholics based in the United States, but with strong ties to Europe. Western Europe may have become “the initial homeland of human rights,” as Moyn contends, but it was in a trans-Atlantic space of exchange and (mis)translation that Catholic human rights gained traction.

Finally, the embattled history of the Committee suggests that Catholic lay activism cannot be easily disentangled from clerical and Vatican priorities. Lay Catholics may have founded the Committee, but its existence depended on clerical backing. When the Committee of Catholics for Human Rights shut its doors in 1940, it was because members of the Catholic hierarchy decided that its views were dangerously open to the possibility of communist contagion—and that advocacy on behalf of Jews was an “annoyance” and an “embarrassment” rather than a boon for the universal Catholic Church.

In this way, “human rights” in the late 1930s was also the stage for the acting out of an internal Catholic battle. Some—including, perhaps surprisingly, the rabidly anti-Semitic Father Coughlin—had bandied “human rights” from the mid-to-late 1930s, to signal a Catholic corporatist response to international communism and free-market capitalism. Others—including the founders of the Committee—used the phrase to argue that the fight for Catholic rights was one and the same as the fight against anti-Semitism and Nazi-Fascism. At the start of World War II, as Pope Pius XII attempted to host his own peace conference for Europe’s warring powers, the Committee of Catholics for Human Rights represented a dangerous liability. It was forced to fold. But this did not mean that the language of Catholic human rights was destined to disappear. To the contrary, in the early 1940s, human rights talk quietly became the preserve of Pope Pius XII. But his aim in using the phrase was not to highlight Jewish suffering; rather, it was to emphasize the centrality of Catholics—and the Vatican in particular—in the construction of a Christian, anti-communist, and anti-liberal postwar order.