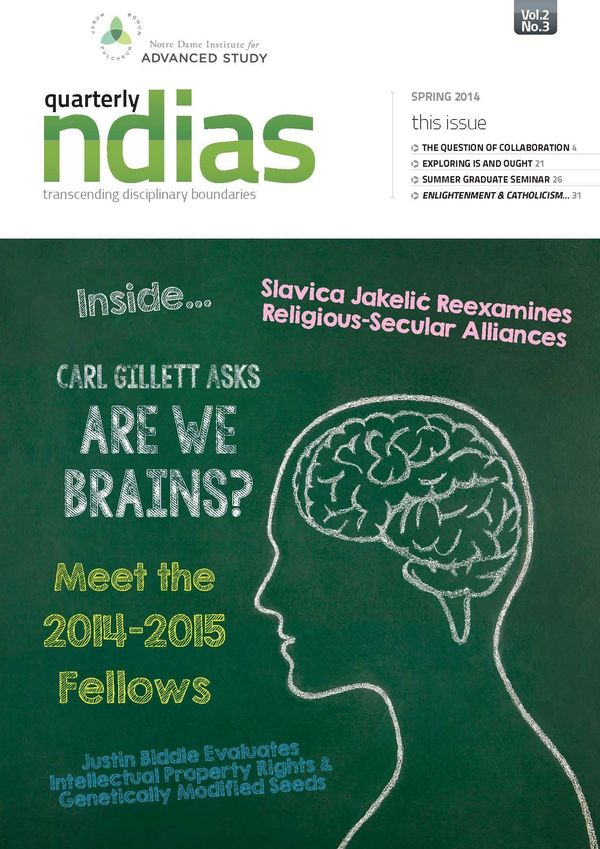

In the most recent issue of The Notre Dame Institute for Advanced Study (NDIAS) Quarterly, TIF contributor Slavica Jakelić, in an excerpt from her book manuscript The Practice of Religious and Secular Humanisms, argues that in order to understand the moral foundation and democratic potential of religious-secular alliances, it is important to move beyond the discourse of power.

In the most recent issue of The Notre Dame Institute for Advanced Study (NDIAS) Quarterly, TIF contributor Slavica Jakelić, in an excerpt from her book manuscript The Practice of Religious and Secular Humanisms, argues that in order to understand the moral foundation and democratic potential of religious-secular alliances, it is important to move beyond the discourse of power.

Although religious-secular alliances transformed the political and social landscapes of the contemporary world, they are still mostly shrouded in a veil of silence. What are the reasons for that silence? Why don’t we talk more and know more about the collaboration between socialist and Catholic labor union leaders, between [Martin Luther] King and Asa Philip Randolph, between Father Józef Tischner and Adam Michnik in Poland, between Bishop Desmond Tutu and Chris Hani in South Africa?

One of the important reasons for the lack of discussions about such collaborations is the focus on conflict that has long defined our thinking about religions and secularisms. The emphasis on conflict, it is important to underline, is not without foundation. Historically, it highlights the real events in which religions and secularisms confronted each other—from various religious rejections of the secularizing aspects of modernity (liberalism and revolutions, religious freedom, and even democracy) to the anti-religious policies of the Soviet communist states (ranging from direct religious persecutions to more sophisticated modes of religious oppression and control). Sociologically, the view of religious-secular relations as defined by confrontation mirrors growing doubts about the secular states’ ability to address the challenges of pluralism. This view also stems from the persisting suspicions that some secularists and some believers have toward religious organizations and communities that demand a place and voice in public life.

Read the full essay here.