Several months ago, it seemed religion might be a notable factor in the 2012 presidential election. While the economy was number one, two, and three on most voters’ minds, religious issues were not too far behind: recall the religious rhetoric during the Republican primaries, tensions between the president and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (especially in regards to the so-called contraception mandate), and debates over the significance of Mitt Romney’s Mormonism for evangelical voters. However, some analysts are asking whether religion played a different kind of role in the 2012 election compared to recent years, when the conversation about religion and politics has often been dominated by the religious right.

Several months ago, it seemed religion might be a notable factor in the 2012 presidential election. While the economy was number one, two, and three on most voters’ minds, religious issues were not too far behind: recall the religious rhetoric during the Republican primaries, tensions between the president and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (especially in regards to the so-called contraception mandate), and debates over the significance of Mitt Romney’s Mormonism for evangelical voters. However, some analysts are asking whether religion played a different kind of role in the 2012 election compared to recent years, when the conversation about religion and politics has often been dominated by the religious right.

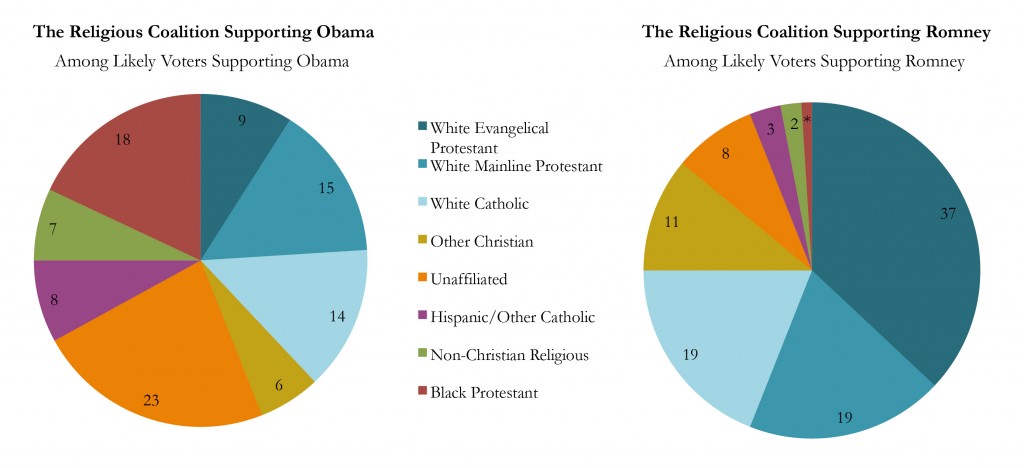

Just prior to the election, both the Public Religion Research Institute and The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life released new surveys documenting the diversity and fluidity of the American religious landscape and its relationship to politics. While Mitt Romney’s religious coalition was dominated by religious whites (whether Catholic or Protestant), Barack Obama’s religious coalition was more racially, ethnically, and religiously diverse, including the majority of Black Protestants, Latino Catholics, and Latino evangelicals as well as the majority of religious “nones.” CNN exit polling data suggest that Obama also carried a sizable majority of religious “others.”

Now that the election is over, exit polls are confirming what pre-election polls found, as Sarah Posner at Religion Dispatches notes:

How did President Barack Obama just win a second term, prevailing in evangelical (and Catholic) intensive states like Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Iowa, Ohio, and Virginia? By winning among voters other than white religious conservatives.

If you had listened to Ralph Reed or Tony Perkins, you might have thought the mighty values voters of 2004 were going to turn out in huge numbers and tip the election to Mitt Romney. Instead, he lost, as did the Republican Party’s worst specimens in the culture wars: the rape apologists Todd Akin and Richard Mourdock. And marriage equality has passed in two states (as of this writing, Maryland and Maine), and pot was legalized in Washington and Colorado. (Brace yourself for tomorrow’s apocalyptic conference calls, emails, op-eds, and press briefings.)

But what went wrong for Reed, Perkins, et al.?

They represent a coalition in decline—white religious conservatives—while Obama has a more diverse one, made up of various religious and non-religious voters, whites, blacks, and Latinos. This story has been emerging even before the election.

That the landscape is no longer dominated by the Christian right is supported by the day’s other results, including support for same-sex marriage, women’s health, and marijuana legalization, as well as the election of the first openly gay senator (Tammy Baldwin), first Buddhist senator (Mazie Hirono), and first Hindu in Congress (Tulsi Gabbard). Over at CNN, Dan Gilgoff writes:

Before the election, many evangelical leaders predicted that opposition to Obama over his support for abortion rights, his personal endorsement of same-sex marriage and his vision of government as a force for good would trump reservations evangelicals had about Romney’s past social liberalism and his Mormon faith.

“There is no evidence in voting patterns that President Obama’s ‘evolution’ on same-sex marriage cost him anything,” [Albert] Mohler said in another tweet Tuesday night.

Noting a “changed and changing electorate,” following Obama’s decisive victory, Albert Mohler, president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, called for reflection and self-examination:

Fundamental changes to the American electorate also became evident. Vast demographic changes mean that the electorate is far more ethnically, culturally, and ideologically diverse. The electorate is becoming more secular. Recent studies have indicated that the single greatest predictor of voting patterns is the frequency of church attendance. Far fewer Americans now attend church, and a recent study indicated that fully 20% of all Americans identify with no religious preference at all. The secularizing of the electorate will have monumental consequences.

America is becoming more urbanized, and this also changes voting patterns. Younger voters are disproportionately identified in ethnic terms, pointing to long-term electoral shifts. Fewer Americans are married and fewer have children in the home. This, too, changes voting habits. These are just a few of the factors pointing to a fundamental change in the nation.

Indeed, the size and significance of religious voting blocs is unclear. At Boston Public Radio (WGBH), Michele Dillon sat down to talk about the myth of a Catholic voting bloc, while Rachel Zoll discusses the voting trends among American Jews. It is obvious that religious Americans represent an important part of the electorate, but in future electoral cycles, campaign strategists will need to rethink how to appeal to religious people given the diverse and often fractured quality of the religious landscape today.