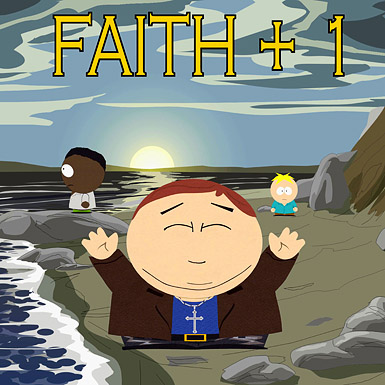

Meghan O’Gieblyn, writing for Guernica, forays into the history of CCM, or Christian contemporary music, which also happens to be that of her own adolescence, tracing the gradual displacement of the more overtly gospel elements of Christian pop, rock, and rap, as the Christian music industry, in its growing drive for “relevance,” felt the squeeze of secular music, especially under the pincers of the more profitable and marketing-savvy MTV (back when it played music, that is).

Meghan O’Gieblyn, writing for Guernica, forays into the history of CCM, or Christian contemporary music, which also happens to be that of her own adolescence, tracing the gradual displacement of the more overtly gospel elements of Christian pop, rock, and rap, as the Christian music industry, in its growing drive for “relevance,” felt the squeeze of secular music, especially under the pincers of the more profitable and marketing-savvy MTV (back when it played music, that is).

More than the fate of explicitly Christian popular music, this course, O’Gieblyn suggests, reflects the simultaneous devolution of a distinctly evangelical way of being in the world, which, stuck as it may be between oppositional self-cloistering and secularizing dissipation, seems to O’Gieblyn to have tended toward to the latter.

The whole process, in any case, has not been without certain ironies. From the article:

In the mid-’90s, MTV was producing a product superior to just about anything pitched at teens, largely due to its revolutionary market research. The Brand Strategy and Planning division of MTV was a new department dedicated to researching kids in the channel’s target demographic (ages twelve to twenty-four). They conducted hundreds of in-depth ethnography studies, where researchers would visit a typical fan—say a sixteen-year-old girl—in her home. Armed with a clipboard and trailed by a camera crew, these researchers would hang out in the fan’s room and listen to her talk about her favorite pair of shoes, or what’s in her CD player, or her relationship with her boyfriend.

The department also conducted focus groups that brought together teens who had been identified as “leading-edge thinkers and tastemakers and stylemakers” in eighteen American cities. Another study polled three hundred kids from up-and-coming neighborhoods of New York and Los Angeles to find out what they were listening to. Additional research was contracted to “cool-hunting” companies like Youth Intelligence that had hundreds of field correspondents snapping photos of street fashion, getting down in mosh pits, chatting up kids outside bars, and collecting similar information that was compiled and sorted into a web database to which MTV—along with other clients—subscribed for an annual six-figure fee. “It’s principally to make our programming relevant,” Todd Cunningham, Senior Vice President of Brand Strategy and Planning at MTV, said in a 1995 interview. By comparison, the CCM market of this era seems tragically naïve. Christian bands could mimic what was already mainstream, but it was difficult to compete with a product created with the help of millions of dollars worth of demographic research. Cultural relevance could be bought, and MTV, part of media conglomerate Viacom, had a very large budget.

[. . .]I spent the following years obsessively listening to the radio and befriending the youth group kids whose parents didn’t child block MTV. I wrote down the names of bands I didn’t know, then biked to the local record store, Believe in Music, and spent my babysitting money on albums I had to smuggle back to my room. With very few exceptions (i.e. Disney soundtracks) my parents didn’t let me listen to secular music, but there were a few bands I managed to pass off as Christian, like Soul Asylum or Collective Soul. It was an easy feat at the time: Christian rock was becoming more sophisticated and the secular industry was oddly fascinated with God. Artists on heavy rotation on MTV included Joan Osborne: “If God had a name, what would it be and would you call it to his face?” Alanis Morrissette: “I am fascinated by the spiritual man,” Counting Crows: “She says she’s close to understanding Jesus,” and Tori Amos: “I’ve been looking for a savior in these dirty streets.”

This wasn’t coincidental. One of the “macro trends” MTV uncovered in their research was a growing interest in spirituality among teens. “Trendsetters feel as if music today has no depth, no meaning,” Cunningham said. “They are looking for meaning from their music. And music that expresses their search for meaning.” The Music Trendsetters Study coined the word “pessimysticism,” an attitude that expresses “a simultaneous dissatisfaction with the inauthenticity of commercial music, and a search for higher emotion and expression in music.” For most of my high school years, I noticed an odd disconnect: everyone at church was bemoaning the fact that kids were no longer interested in spirituality, and yet all I heard on MTV was stuff about God. As CCM strove to keep up with an industry teens resented for its spiritual vacuity, MTV reached the acme of its marketing genius: its ability to take its audience’s disenchantment with commercialism, repackage it, and sell it back to them.

The entire article, which makes for quite an interesting reading, is available here.