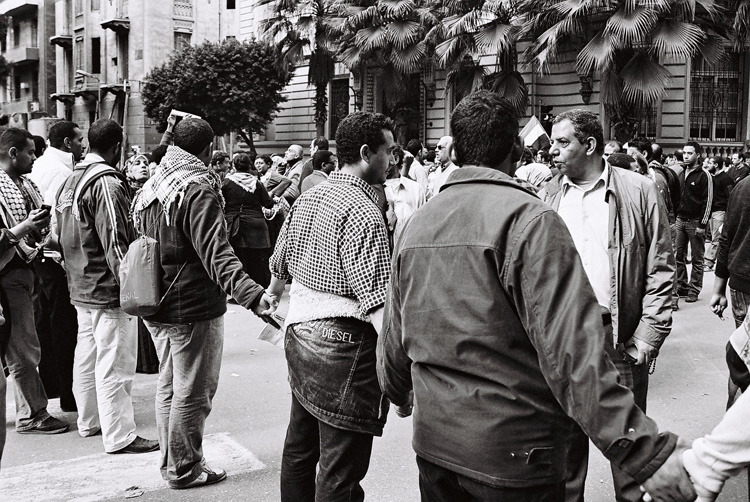

In The Nation, Saba Mahmood weighs in on the factors that facilitated the historic events recently witnessed in Egypt, and the tasks that lie ahead now that Mubarak has been removed from power.

In The Nation, Saba Mahmood weighs in on the factors that facilitated the historic events recently witnessed in Egypt, and the tasks that lie ahead now that Mubarak has been removed from power.

Mahmood identifies a wide range of contributing factors, which include the Tunisian example, widespread labor unrest, frustration with police repression and corruption, and—echoing Charles Hirschkind—the blogosphere and other social media.

Looking forward, Mahmood writes:

With Mubarak’s resignation, these architects of the Egyptian revolution face a series of daunting tasks—key among them ensuring not only civil and political rights for the vast majority of Egyptians but also economic justice for the millions who exist on less than $2 a day. While there is no doubt that the new order in Egypt cannot do without the civil and political liberties characteristic of a liberal democracy, what is equally at issue in a country like Egypt is an economic system that serves only the rich of the country at the expense of the poor and the lower and middle classes. The vast majority of public institutions and services in Egypt have been allowed to fall into a dismal state of disrepair. Countless Egyptians die in public hospitals for lack of medical care and staff; Egypt’s universities are no longer capable of delivering the education of which they once boasted. Lack of housing, jobs and basic social services make everyday life impossible to bear for most Egyptians, as do declines in real wages and escalating inflation. It is these conditions that prompted the workers—from the industrial and service sector—to stage strikes and sit-ins over the past ten years. These workers were an integral part of the demonstrations over the past two weeks in Egypt; various unions formally joined the protests in the days immediately preceding Mubarak’s resignation, prompting some to suggest that this was a turning point in the evolution of the protest.

While a new democratic regime might ensure civil and political rights within the framework of a liberal democracy, it is unclear whether the reforms necessary for addressing economic injustice and inequality can be implemented within this framework. Since the 1970s, the Egyptian economy has been increasingly subject to neoliberal economic reforms by the World Bank, the IMF and USAID at the behest of the United States government. Egyptian elites have been beneficiaries of, and partners in, these American-driven reforms. Will this sector of Egyptian society accommodate the demands of the poor, the unemployed and the workers who have so far been equal partners in their struggle against political corruption and autocracy? Will the protestors in Tahrir Square continue to fight for economic justice even as they gain political and civil rights in the months to come?

Read “The Architects of the Egyptian Revolution” here.