Recently, in The Atlantic, Alan Jacobs interviewed Ahron Varady and discussed how technology can aid traditional religious practices. Varady runs the Open Siddur Project, which creates an online database of siddurs, a Jewish book of daily prayers, and gives the public the opportunity to create their own siddur. Varady seeks to encourage creativity and openness in Jewish spiritual practices. Jacobs explains:

Recently, in The Atlantic, Alan Jacobs interviewed Ahron Varady and discussed how technology can aid traditional religious practices. Varady runs the Open Siddur Project, which creates an online database of siddurs, a Jewish book of daily prayers, and gives the public the opportunity to create their own siddur. Varady seeks to encourage creativity and openness in Jewish spiritual practices. Jacobs explains:

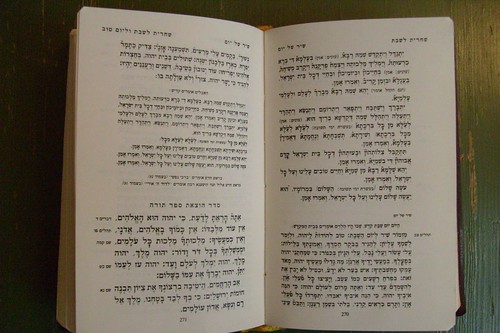

One might think that a highly traditional religion like Judaism — whose core practices are so ancient and burnished by custom — would be inclined to techno-suspicion. But Aharon Varady doesn’t see it that way: for him, digital technologies can come to the aid of traditional practices. Varady is a man of wide-ranging gifts who, among other things, runs the Open Siddur Project. A siddur is a Jewish prayer book containing the daily prayers, and the Open Siddur Project is working to create the first comprehensive database of Jewish liturgy and liturgy-related work — and to provide an online platform for anyone to craft their own siddur. In this way Varady hopes “to liberate the creative content of Jewish spiritual practice as a commonly held resource for adoption, adaptation, and redistribution by individuals and groups.” For him, openness is key to the success of the project.

The Open Siddur Project strikes me as a deeply thoughtful, innovative way of trying to make new technologies and modern religious life reinforce each other, instead of being inimical or at cross-purposes. So I proposed that Aharon answer a few questions about the ideas behind his work, and he readily agreed. Here’s our conversation.

You describe Open Siddur as a project in “open-source religion.” What do you mean by that?

Varady: A couple of years ago, after I started the Open Siddur Project, I thought I’d write a statement on my website about what I was doing. For the previous six years I had been working as an urban planner, so some statement was needed to be written for professional contexts and old friends googling what I was up to. I wanted to put my work in some wider secular context, because it was undeniably a Jewish and a religious project. At the same time it was a digital humanities project, a collaborative transcription project, a 21st century realization of ideas set down in the 19th century by William Morris, a free/libre-culture and an open source software project. And so I wrote that i was “researching open source religion in general, and in particular, how the free culture movement can aid in bridging individual creativity and meaning making with tradition and cultural relevance.”

For the full interview, click here.

A very similar thing is going on in Catholicism with people praying the Divine Office via their Kindles.