Off the cuff is a new feature at The Immanent Frame, in which we pose a question to a handful of leading thinkers and ask for a brief response. Our question today concerns the issue of homosexuality in debates about the Anglican Communion.

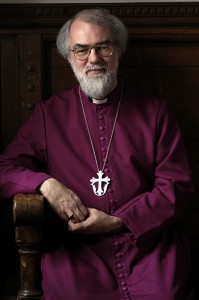

As the New York Times reported last week, in response to the Episcopal convention in Anaheim earlier this month, and in light of “profound rifts over sexual issues within Anglicanism,” Rowan Williams, Archbishop of Canterbury, has released a statement addressing the issues of gay clergy and same-sex unions.

As the New York Times reported last week, in response to the Episcopal convention in Anaheim earlier this month, and in light of “profound rifts over sexual issues within Anglicanism,” Rowan Williams, Archbishop of Canterbury, has released a statement addressing the issues of gay clergy and same-sex unions.

The Archbishop here signals support for the human dignity and civil liberties of LGBT people. While suggesting that the Anglican Communion recognize “two styles of being Anglican,” however, he also argues that “a certain choice of lifestyle has certain consequences.” The Church, he writes, will only change its stance on the blessing of same-sex unions after they have been justified by “painstaking biblical exegesis” and subsequently widely accepted within the Communion. Until that point, a member of a homosexual couple will continue to be treated just as “a heterosexual person living in a sexual relationship outside the marriage bond.”

In light of both the ongoing conflict within the Anglican Communion and the Archbishop’s latest missive, we ask: why has homosexuality persisted as a divisive issue for religious traditions and communities, within the Anglican Communion and beyond? And what are the likely effects of the Archbishop’s recent intervention?

Mary Anne Case, Arnold I. Shure Professor of Law, University of Chicago Law School

Eric Fassin, Professeur agrégé, Ecole normale supérieure (Paris)

Siobhán Garrigan, Associate Professor of Liturgical Studies and Associate Dean for Chapel; Yale Divinity School

Jimmy Casas Klausen, Assistant Professor of Political Science, University of Wisconsin at Madison

Mary-Jane Rubenstein, Assistant Professor, Wesleyan University

Emilie M. Townes, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of African American Religion and Theology, Yale Divinity School

______

Mary Anne Case, Arnold I. Shure Professor of Law, University of Chicago Law School

Mary Anne Case, Arnold I. Shure Professor of Law, University of Chicago Law School

I fear those who support equal rights and equal rites for gay couples and individuals, whether in faith communities or in law, tend to underestimate the extent to which a commitment to traditional sex roles rooted in the subordination of women motivates the opposition. Among Baptists, a division that began with two views of Negro slavery has continued to this day with two views of women’s role in the leadership of the Church and the family. In the Anglican Communion, many of those who now oppose the ordination of gay people in committed relationships also opposed the ordination of women. A bishop’s miter remains for some among those things “which pertaineth unto a man” and should be forbidden to a woman, whatever her sexual orientation.

Rowan Williams tells Anglicans to take “due account…of the teachings of ecumenical partners” in formulating answers to questions of homosexuality. The head of one of those partners, Pope Benedict XVI, has been quite clear and direct in linking his Church’s recent teachings on homosexuality, on the ordination of women, and on heterosexual marriage in a theological anthropology of essential sex and gender differences. Benedict analogized what he saw as the growing disregard for the essential “nature of the human being as man and woman” to the destruction of the rainforest in his December 22, 2008 address to the members of the Roman Curia. Given the historical exclusion of women from decision-making in the Church, Rowan Williams’s invocation of the “venerable principle” that “what affects the communion of all should be decided by all” (“Quod Omnes Tangit”) as a brake on change in the direction of freedom and equality in matters of sex and gender is, as one of Boccaccio’s heroines suggested on Day Six of the Decameron, deeply problematic.

______

Eric Fassin, Professeur agrégé, Ecole normale supérieure (Paris)

Eric Fassin, Professeur agrégé, Ecole normale supérieure (Paris)

Homosexuality is certainly a divisive issue within the Anglican Communion—but it may also be the one concern that unites most religions today, from various Christian denominations to the Islamic world. The point is not so much the homophobia, but the obsession: why does it matter so much? For example, in 2005, for the first time in its history, the Roman Catholic Church decided to systematically exclude from its future ranks not only gays, but also gay-friendly priests. Apparently, this is a priority—and not only for the Vatican.

To understand what is at stake, think of the connection between Rowan Williams’s recent statement on homosexuality (July 27, 2009), and his earlier one on Islam (February 5, 2009). The archbishop of Canterbury caused an uproar when he suggested that the introduction of Shariah in British family law was “unavoidable.” What this meant was that civil law should accommodate religious rules in general. Conversely, what the reaction to the homosexual menace implies is that churches need not accommodate social transformations. Clearly, the problem of secularism still boils downs to: which comes first?

But why should same-sex unions have become a litmus test for religious institutions? This has to do with what I propose to call “sexual democracy.” We live in societies that claim to define their own laws and norms in immanent terms, i.e. without reference to any transcendent foundation. In reaction, for religious authorities, natural law redefined as the biological law of nature can become the last refuge of transcendence. To such theologians, sexual difference may be the last, best hope of God on earth—while the social recognition of (unnatural) homosexuality appears as the ultimate frontier of denaturalization. Hence Pope Benedict’s melancholy call last Christmas for a “human ecology,” intent on preserving the “rainforests” of heterosexual marriage against sexual democracy.

______

Siobhán Garrigan, Associate Professor of Liturgical Studies and Associate Dean for Chapel; Yale Divinity School

Siobhán Garrigan, Associate Professor of Liturgical Studies and Associate Dean for Chapel; Yale Divinity School

You’ve got to feel sorry for Rowan. The man who once appointed the first openly gay bishop in England is now reduced to waiting for an end to biblical literalism before even thinking about gay marriage. Ah, politics.

Last week’s statement is both the same-old same-old and worryingly new. What’s same-old is the dread of schism, post-colonial guilt, racial and cultural misunderstanding, resentment of the USA, and misrepresentation of human sexuality (“lifestyle choice”?). What’s new is the tone of impatience—with LGBT issues and the Episcopal Church’s response to them.

But doesn’t the threat to Anglican unity come more from the same-old issues than from the discovery of the gay Gene? Why, then, be impatient about homosexuality?

Homosexuality represents the loss of the Church’s historically core trope of theological, communal and personal self-understanding: a man fucking a woman. Think Christ and his bride, the bishop leading “her” his church, the heterosexual couple who qualify for their “representative role” (representing the church) by virtue of the marriage bond. If you have two homosexuals making their home together, then who, as the old joke has it, wears the trousers? Such a “confusion” of power and such a denial of the “natural order” seems not unlike Africa running itself, calling God “Mother,” or immigrants having rights… Homosexuality is thus scapegoated because, as it is driven out to the wilderness (another “lifestyle choice”?), it can be blamed for the fall of supposed civilization as we know it.

The witness of LGBT Christian lives and the Episcopalian response is prophecy, not heterodoxy. Sadly this will probably only be recognized once this goat has been sacrificed and the same-old problems predictably persist nonetheless.

This subject warrants far greater examination, so please come to the conference “Why Homosexuality? Religion, Globalization and the Anglican Schism,” Yale University, October 17th 2009.

______

Jimmy Casas Klausen, Assistant Professor of Political Science, University of Wisconsin at Madison

Jimmy Casas Klausen, Assistant Professor of Political Science, University of Wisconsin at Madison

In his 27 July statement, the Archbishop of Canterbury seems desperate to avoid the specter of authoritarianism in the Anglican Communion. Even if the Church of England now prefers to understand itself as a hegemon in the old sense—a leader among equals—it cannot ignore Anglicanism’s imperial hangover: its list of provinces reads like a brief from the Ages of Exploration, Colonization, and (direct or free-trade) Imperialism. So when the Archbishop enjoins “mutual recognisability, mutual consultation” among churches in order to avoid “mere federation” or (worse) pluralism, I can’t help but think that such practices of “mutual responsibility” still aren’t so mutual.

Let’s be clear about what “two styles of being Anglican” seems to mean.

EITHER the venerable Body of Christ model, whose head governs and represents its members: the Archbishop says explicitly that the “place” of “LGBT people” in that Body is not open to challenge, but, because same-sex marriage does not represent the recognized policy of that whole Body, then same-sex-partnered clergy cannot stand as/at the representing head;

OR the model of networks: “liberal” churches supporting non-heterosexual clergy and “conservative” churches opposed to them consociating separately.

What, if not imperial inertia and the headiness of the top-down model of policy, could blind one to the fact that there have always been many more than two styles of being Anglican, that it’s not a Hobbesian decision between a “theologically coherent” Body or else apocalyptic anarchy? It’s not homosexuality tripping up the Communion. The logic of the Body Politic model of sovereignty and representation willfully ignores consociationism’s enduring infrapolitical reality.

The Archbishop’s encouragement “to act and decide in ways that are not simply local” is surely a glorious goal—but mutual responsibility would be achieved truly consistently through the pluralism of overlapping communities with multiple heads, multiple bodies, multiple spirits.

______

Mary-Jane Rubenstein, Assistant Professor, Wesleyan University

Mary-Jane Rubenstein, Assistant Professor, Wesleyan University

Toward the end of Three Guineas (1938), Virginia Woolf takes a moment to marvel at the recent findings of the Church of England’s Commission on the Ministry of Women. Although it found no theological support for the position, the Commission continued to bar women from the priesthood because doing so reflected “the mind of the Church.” In short, the Commission declared that the church should not ordain women because it did not ordain women.

We can see the same strange logic at work in Rowan Williams’s recent statement, which asserts that the Communion will not accept gay bishops or same-sex blessings because there is no consensus on the matter. It might change its mind after “painstaking biblical exegesis and…wide acceptance of the results within the Communion,” but considering such painstaking exegesis has been done for at least half a century, we are thrown back upon the same position that baffled Woolf: the Communion will change its mind when the Communion has changed its mind.

So why is homosexuality so threatening to Anglicanism? One possible answer is that homosexuality has re-opened unhealed wounds over women’s ordination (eighty years after the debate began in earnest, Blackburn Cathedral is offering male-consecrated wafers to anyone who refuses the authority of its female canon). Another is that a Falwellian culture war has been foisted upon the two-thirds world. Another is that the Global South is redeploying a Victorian gender code against the very people who imposed it upon them.

But the interpretation I would like to hear the Archbishop of Canterbury address is one that he offered himself, before his own mind melded with that of The Church. In an essay entitled “The Body’s Grace” (1989), Williams suggests that the problem with homosexuality is sexuality itself. Unlike heterosexual relationships, which the Church can reduce to reproduction, “same-sex love annoyingly poses the question of what the meaning of desire is—in itself, not considered as instrumental to some other process.” Facing desire itself, we face our own vulnerability—to loss, to humiliation, and to joy. Williams then goes on to sketch non-reproductive desire as an image of God’s (often unreciprocated) yearning for humanity, grounding his vision in Hosea, Samuel, and even Paul. If anyone can still stomach it, then, those who undertake the “painstaking exegesis” for which the Archbishop calls would do well to start with his own.

______

Emilie M. Townes, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of African American Religion and Theology, Yale Divinity School

Emilie M. Townes, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of African American Religion and Theology, Yale Divinity School

As long as we shape our theologies and spiritualities around simplistic Cartesian dualisms, we will continue to see homosexuality thrive as a divisive issue for Christian religious traditions. This temptation to live in split bodies and souls as signs of righteousness means that we fail to develop a richly embodied faith. Instead, we are content to live an antiseptic faith that takes the smells, sights, and sounds of life coming into life such that we have pristine crèches of Jesus’ birth rather than the fecundity of a stable. We then extend this to a deep wariness of our bodies because we fail to see the importance of weaving ourselves into faithful living—body and soul.

This finds an all too comfortable home when it comes to talking about sex and sexuality, race and racism, class and classism, and so on. We believe that parts of our being are inferior to other parts of our being, which leads many to isolate homosexuality as a set of acts (usually only sexual and deemed deviant) rather than as one of the many ways our identities are shaped in God’s good creation. While I am a frequent champion of what I call “fearless Bible study” in our churches, this must be done in rigorous conversation and study with ethics, theology, biology, history, sociology, and more. For I am convinced that God’s revelation for and to us is found in the richness of unfolding the Bible into life and life into the Bible such that we begin to develop a deeper and richer appreciation of the power of covenant and commitment as profound biblical themes signaling faith-filled living. The assumption that heterosexual marriage is the highest expression of human bonding is a theological leap that ignores the infinite promises found in love.

If the divide in Anglicanism is over homosexuality (and I’m not as convinced as “The Editors” are that this explains the divide in any very sufficient sense), it seems that an interesting divide in this panel is based on deliberative structures in communion. Case and Rubenstein seem to be opposed to the voice of the Communion as a whole being so significant an element, while Garrigan emphasizes the role of prophets in the people of God (it could also be asked whether this prophetic demographic she cites represents 815, or “the people”, or a political interest, or…). Klausen, perhaps, offers the most realistic perspective in questioning the straightforwardness of these structural alternatives.

By way of rounding up the other two panelists in a brief response, I think that Townes does a good job of identifying why certain superficial issues become divisive for the communion. Yet Fassin seems to me to say just the opposite- that these issues of sexuality are divisive precisely because the dualisms Townes sees have been collapsed into the natural. Are both of these perspectives correct on their own terms, or do they contradict at some level? Does Fassin’s critique apply merely to “conservative” theologies of sexuality, or to Williams’ own thought on the body’s grace?

Speaking of which… where does Rubenstein’s mention of this essay bring us? Does Williams seek to de-naturalize sexuality in speaking of it apart from literal, technical sexual function and in terms of desire? Does this make the body a more immanent thing and fall prey to Fassin’s critique of a desperate rush to human ecology by the Church? Or is it, in its focus on a desire that transcends the body’s reproductive work, a more dualist thing and guilty of Townes’ critique?

These questions don’t seem to be addressed, as everyone seems to have their cross-hairs trained on those whom they presume (wrongly, I think) to be looking at sexuality as a yes/no, make/break issue for the communion. Many important critiques are made of these binaries, but I think that just as many are introduced, and in a panel format like this, the new binaries have come out it pretty sharp relief.

I take Williams’ remarkable patience and restraint (considering his private convictions on the matter) to be a sign of a deep commitment to hearing the voice of Christ in his Church, particularly among Anglicans in the developing world. That African, Asian and Latin American Anglicans might have something to say, and that that something might issue from an authentic voice (that is, one not merely constrained by imperialism) empowered by God’s Spirit, continues to be contested or ignored by the West. What a shock of sad irony.

Wow thanks loads for asking, with all these different clear-spoken thinkers.

I really do think Rowan Williams is sadly reducing himself to a standard Pater Familias Role, wherein he rants and raves about his queer son above all, probably nearly completely ignoring his lesbian daughter—she’s off on a Peace Keeping Mission with the fifty-seventh armored division?—and thundering that This Family Will Not Invite the son’s black lover to the upcoming family dinner.

He’s not changing his mind either—until and unless every other single Father on the face of the planet has changed their minds. Okay, so there. End of discussion. Oh Papa, you have a call waiting—It’s Benedict something or other.

So this is what these brilliant minds came up with: the issue of homosexuality boils down to the oppression of women (Case), Cartesian dualisms (Townes), imperialism (Klausen), and the loss of the church’s favourite metaphor (Garrigan)? And Rubenstein’s oversimplification is irresponsible and absurd. These academics are the real narrow-minded ones, for they can’t break out of the little clever paradigms they were taught when they went to grad school and so they have to see every issue in terms of their favourite deconstructive schema. The only person who made any sense at all, and I think stumbled onto part of the issue, is Fassin. If these academic answering-machines (just repeating the mind of their alma mater) would actually engage in the issues being considered by Anglicans, rather than just trying to deconstruct or categorise everything, then maybe they would have some semblance of real insight. This is cheap, shallow analysis, not worth the bit of space it takes up on the server.

I am so glad I’m an atheist. You pay for these people to invent reasons for doing things you’re doing anyway. I can’t believe parents pay for the salaries of “subjects” like religion or liturgy. The fastest growing segment of the US population is “None of the Above”; one fourth of those between 16-30 are unaffiliated. The sooner these “scholars” are preaching to empty classrooms the better.

I take Williams’ remarkable patience and restraint (considering his private convictions on the matter) to be a sign of a deep commitment to hearing the voice of Christ in his Church, particularly among Anglicans in the developing world.

Here is the problem with the “supposed” Church, and some professing Christians; adhering to their own corrupt reason, rather than what the Word of God actually says. God doesn’t want philosophizing, he wants a relationship based on covenant obedience.

As a congregant in this ruptured communion I think Fassin’s response has the most potential to be helpful. Garrigan’s is the least helpful. A man fucking a woman is the “historically core trope” of Christianity? Really? If that’s true then why bother weighing in on what some fallic head of a misogynistic institution has to say about same-sex unions? That annoys the crap out of me.

My main conundrum is why this question? Why are we analysing this? If you’re not devoted to the Church I can see the strange fascination an outsider might have with our queer disagreements, but for the Body the real work before us is not wondering why we disagree, but doing precisely what Williams is doing and calling us to do: struggle and sweat for unity in love.

Like I said, Fassin might have something, and it may come in handy, but as I sit at tables across from people I love and with whom I disagree, I don’t need more theories about why they are so wrong.

Garrigan’s complaint that Williams is quixotically waiting for the end of fundamentalist, biblical literalism to take effect and Rubenstein’s observation that the “painstaking exegesis” Williams wants has been going on for a while now made me think of Richard Hays’ chapter on homosexuality in his book “Moral Vision of the New Testament.” There is a precedent for the Church’s acceptance of a group that was formerly considered outside the bounds, namely the acceptance of the Gentiles after Peter’s vision on Cornelius’ house in Acts 10. What effected this shift, however, was not just Peter’s vision, but reexamining the scriptures to find that they had said this all along.

Hays’ application of this precedent to the homosexuality issue is that if homosexuality is to be an appropriate and acceptable lifestyle within the Church, then it needs to be show that this reexamination of the passages that concerned homosexuality reveals that it could be acceptable. Hays’ concluding statement of these passages is that homosexual practices are not acceptable and that the Christian homosexual is in much the same position as the single heterosexual of having to live a life of chastity.

I suspect, in light of what I know of his own personal beliefs on the matter, that Williams would not agree with Hays’ assessment, but that he is looking for this how this precedent might be fulfilled in the homosexuality case. This would not be a matter, I think, of placating to the literalists, but looking for a way to reinterpret a common source of inspiration within the Communion so as to hopefully help heal the wound that has formed in the Communion. It won’t do for Williams to just come down from on high and give an Anglican version of a papal bull on the matter. That would seem too authoritarian for Williams’ style and would not help in healing the wound that’s formed. The union for Williams is ultimately more important than an individual issue.

Case’s analysis strikes me as incredibly correct. Her position is not that homophobia boils down to the oppression of women as one commentator suggested but rather that the edification, ontologization, and centuries of reification of a binary and hierarchical gender system almost completely account for the situation of the Anglican Church. We all know how things work according to such a system: Woman is subordinate to a Man and thus cannot enter the clergy, which would imply a disruption to her ‘natural’ subordination. Man’s role, accordingly, is to be superior to the Woman, and his sexual energy is to be used for coitus with her.

Of course, this sounds cliché and simplistic partly because feminists have been rightly railing about it for a half-century, partly because we have all seen countless examples of this through the media and our everyday lives, but partly because of something else. This account of gender/sexual relations sounds simplistic and an inapt description of the world because this ‘natural order of things’ is starting to be displaced by something else. Men and women are slowly but steadily rejecting their predetermined roles. For those who cling and appeal to this soon-to-be antiquated organization of life are especially peeved, and for them, homosexuality represents one of the most fundamental breaks with the ancien régime. Why is that? Well, it seems that gendered ways of behaving other than sex (e.g. bodily comportment, choice in occupation, manners of dress) can be more easily recognized as constructed; whereas, compulsory heterosexuality can still seem to many as natural.

Finally, I found it clever that Case alluded to the historic debate among Anglicans over Black slavery. That debate as well centered around a created system of social organization that became ontologized. Under the racial/racist classificatory scheme that underlay slavery, Blacks were not just people with more melanin that happened to work for Whites given particular historical events; rather, Blacks were inferior to Whites and accordingly did not deserve the same respect accorded to fellow White people. Some Anglicans agreed with this system while others rejected it, but eventually the Church as a whole rejected it. If I’m right that the tide is turning in favor of increased deviation from the normalizing sex-gender-orientation complex, it will only be a matter of time until it is likewise rejected by the Church.

I think Eric Fassin has well identified the mind set of the conservative theologians here. What troubles me is that he gives them a pass on the credibility of that mind set. Is it credible to continue placing what have been repeatedly revealed as socially constructed understandings of gender roles in the mind of G-d, thus attempting to move such understandings beyond any kind of critical reflection? What is intellectually or spiritually respectable about such a move? Is it credible to hold to understandings of “nature” and “tradition” frozen in the cosmology of the pre-Enlightenment era and offer them as somehow transcendent of time and culture? Again, what would be intellectually or spiritually respectable about such an approach? Have we learned nothing from the Galileo debacle? At a very basic level, Fassin’s argument seems to be an example of the naturalistic fallacy, confusing what the church has always said with what it ought to say in light of the evidence which draws those former understandings into question.

Of course, the church has a right to speak for its own understandings, whether they are ultimately credible (or even offered in good faith, per Sartre) or not. But the church does not have a right to expect those outside its dogmatic borders (and even those of good faith and critical conscience within) to respect such pronouncements. While the church has long valued martyrdom as a proof of faith, it is hard pressed to be seen in such light when it is hoisted by its own petard.

At its heart, the “obsession” over how the church should treat LBGT human beings reflects a crisis of its own integrity. While socially constructed—and thus temporally and culturally conditioned—understandings of gender roles, slavery, and matters of sexuality have always found their way into scripture and church teaching, overarching moral principles of reciprocity found in teachings such as the Golden Rule provide the criteria for assessment and evaluation of such understandings. And in this endeavor, church teachings will ultimately lose. It is simply impossible to love one’s neighbor as oneself and see and treat them in ways which are less than fully human.