Most people associate prayer with moral good: benevolence, forgiveness, healing, and reconciliation. Yet in some cases, people deliberately pray against others in forms of what I call “aggressive prayer” that aim to harm or remove another party. These cases raise interesting questions about the shadow side of prayer. Attention to aggressive prayer and to the unspoken, negative aspects of positive prayer reveals interesting insights into how we might more fully understand prayer as a part of lived religion.

Most people associate prayer with moral good: benevolence, forgiveness, healing, and reconciliation. Yet in some cases, people deliberately pray against others in forms of what I call “aggressive prayer” that aim to harm or remove another party. These cases raise interesting questions about the shadow side of prayer. Attention to aggressive prayer and to the unspoken, negative aspects of positive prayer reveals interesting insights into how we might more fully understand prayer as a part of lived religion.

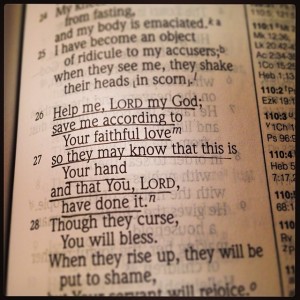

Take a blatant and public example of aggressive prayer. In January of 2012, the speaker of the Kansas House of Representatives, Mike O’Neal, forwarded an email message urging his Republican colleagues to “Pray for Obama: Psalm 109.8.” That scripture reads, “May his days be few; may another take his office.” This is hardly a prayer offered for Obama’s flourishing, and the next line is even more malicious: “May his children be fatherless, and his wife a widow.”

This speech form is known as imprecatory prayer, from the Latin, imprecate, “invoking evil or divine vengeance; cursing.” The use of scripture as a form of imprecatory prayer has long been covertly practiced by both Christians and non-Christians. But the slogan to “Pray for Obama: Psalm 109.8” circulated openly on t-shirts and bumper stickers during the 2008 presidential race. Similarly, Reverend Wiley Drake, the second vice-president of the First Southern Baptist Church, issued in 2006 a statement claiming that his prayers for the death of a slain abortion provider George Tiller had been answered. These instances give us a rare display of imprecatory prayer in the US public sphere, and constitute prime examples of the use of negative prayer in American political life and beyond.

These bizarre cases caught my attention, since cursing and imprecation are usually associated in the popular imagination with my longtime area of research: the traditional Afro-Haitian religion called Vodou. The negative image of Vodou as sorcery is one that I and others have worked to dispel as part of a project of ethnographic redescription. We have worked to humanize Vodou and portray its full role in Haitian society, writing of elaborately developed prayers, liturgical rhythms, and songs, dances, and ritual that serve to mediate between life and death, to construct family, and to heal.

In this non-dualistic Afro-Caribbean philosophical system, good and evil are not understood to be essential absolutes. When one develops the ability to heal, one automatically learns the way to harm. While priests in the Vodou tradition focus on healing, there is a branch of disreputable specialists—disavowed by Vodou priests—who practice a set of prayer rituals and wanga (material “working” objects) that purport to impose the will of the religious actor onto another person or event. The Haitian ritual expert who performs this is called a malfaiteur, (literally: “evil-doer”) and the term for this form of prayer is “malediction” (lit: “speaking evil”). One form such prayer can take—as in the Kansas case—is the reciting of Old Testament psalms for a specific malediction against a person or group.

My research with Haitian spirit-workers reveals that instances of negative prayer are always concerned with a desire for justice or self-defense. For example, I once watched a Haitian spirit priestess in New York City offer her client a remedy for coping with sexual harassment in the workplace. “Pray Psalm 35, let destruction come upon him unawares,” she instructed, “and place a snakeskin in your shoe. You will tread soundlessly and slip away from him while he is destroyed by your guardian spirits.” In this instance, a new immigrant, vulnerable and perhaps undocumented, found in negative prayer a path of recourse against an insidious form of everyday injustice.

Here are two very different religious formations—evangelicalism and Afro-Haitian religion—both using Psalms to pray against others. They force us to consider negative prayer as a part of lived religion. In my work I employ the term “aggressive prayer” as a conceptual, second-order category that encompasses both spoken addresses to the Christian God (or other deities and spirits), and ritual action that aim to harm, debilitate, stop, remove, or weaken another party or to impose the speaker’s will onto another party or series of events. This umbrella term allows us to compare groups that are ordinarily kept quite distinct, such as Christians and self-identified sorcerers.

Just as sorcerers are famous for their deployment of malediction, evangelical Christians are well known for a branch of thought and practice known as “spiritual warfare,” which is also a form of aggressive prayer. Spiritual warfare is a precise term in the evangelical and neo-Pentecostal networks known as the Third Wave Evangelical Movement, or the Revival Movement, whose best-known theologian is C. Peter Wagner of Fuller Theological Seminary. Spiritual warfare is the aggressive prayer needed to fight evil directly in the invisible realm. This can take the form of “casting out evil” through “deliverance prayer,” in which the Christian casts out evil or actual demons from another person under the authority of Jesus (as depicted in Matt. 10:1). More ambitiously, warfare prayer also enables Christian “prayer warriors” to “pray down” more powerful demons—those who have taken over entire areas of geographical territory such as the Islamic world, or propagate widespread sinful activity such as alcoholism—and allow for revival and Christian flourishing to surge in a given area or place. A group of divinely “anointed prayer warriors” understand themselves to be doing battle in the “spiritual realm” with Satan’s high ranking demons, and take their understanding of this war from Ephesians 6:12: “We do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against principalities and powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this age, against spiritual hosts of wickedness in the heavenly places.” Prayer warriors believe we are in a new age in which God is calling prophets and apostles to become intercessors and to usher in the Kingdom of God through warfare prayer. Public figures associated with this movement include Kansas State Representative Mike O’Neal, who “prays for Obama;” the Pentagon’s General William Boykin; Sarah Palin; and Governor Rick Perry.

Spiritual warfare evangelicals have elaborated a complex theology and prayer practice with a highly militarized discourse and set of rituals for doing “spiritual battle” and conducting “prayer strikes” on the “prayer battlefield.” Warfare prayer may take place in church, in large revival events, at semi-public conferences in hotels, or in private spaces such as homes. Prayer warriors may pray openly in “prayer walks” through public spaces, often in cities where poverty and crime are rife. Warriors may also do covert actions in public spaces when they are “on assignment” from the Holy Spirit, in which case they might pray in small groups at key “demonic strongholds,” such as massacre sites, neopagan temples, or abortion clinics.

Is warfare prayer a form of negative prayer? Well, it does seek to impose “God’s will” on others, in specific detail. Muslims are meant to convert to Christianity, Masonic lodges (seen as long standing demonic institutions) are meant to close down, and bars and strip clubs to go bankrupt. In some evangelicals’ narratives, warfare prayer ends with God killing people who are working for demonic causes, such as an Alaskan woman who protested the use of prayer in school board meetings and then died of a heart attack. In such cases, violence or death are God’s judgment, and are part of the overarching cosmic system of perfect justice that evangelicals long to help bring about.

American evangelical prayer warriors teach vehemently against taking a course of physical violence in the material world and becoming actual vigilantes. But in a tragic trend, witchcraft accusations and related killings are on the rise worldwide. United Nations reports show that in locations as diverse as New York City, London, Congo, and Papua New Guinea, people are accusing others of being witches and attacking or murdering them. Often the violence is gendered, with male witch hunters attacking female “witches.” Sometimes people are brutalized or killed during exorcism ceremonies, in which the demons are beaten out of the accused witch.

Studying prayer as it is actually lived in the world means paying attention to such aggressive forms of prayer, and exploring how ideas about negative and aggressive prayer change over time in a given society. We must also open up questions about the negative implications of positive prayer. Logically, even if one prays for positive results in a certain area, it is possible that if it came to pass it would be harmful for someone else. Praying for victory for one side—in war, or in sports—is necessarily to pray for defeat of another side. A prayer for one person to be chosen for a job is a prayer for the other applicants to be rejected. Researchers might ask whether the people praying in any given tradition take into account any possible negative effects of their prayers. Studying aggressive forms of prayer may mean asking how religious actors engage with supernatural forces they perceive to be destructive, such as in exorcisms, or magic, and how they control the ritual so they are not themselves harmed. It means figuring out how explicitly negative prayer is rationalized or even justified by the person praying. Does someone praying negatively imagine themselves to be partnering with destructive or evil forces for their own gain, or do they imagine themselves to be neutral, or even righteous? Perhaps they imagine themselves to be in alliance with forces of ultimate good, which demands an aggressive form of prayer. How is negative prayer tied to conceptions of justice?

More and more studies are considering the positive effects of intercessory prayer and healing, and some argue for tangible results that positive prayer can facilitate medical recovery. It bears considering whether negative prayer has similar negative effects. While it is tempting to imagine that the religious people of the world are all praying beneficently for peace and love, the fact is that all are not. As you read this, someone may be praying against you, wishing you to fail, hoping to be hired in your place, that you convert to their religion, or that “your days be few, and another take your office.”

Consider the way in which psalms are used in Christian monasticism and in particular Evagrius Ponticus’ Antirrhetikon.

Thank you. My family is Christian. I am Buddhist. This explains why prayer has always felt self-serving to me. I have never resonated with it. Too sticky, too attached to duality. It is good to know there is a name for the kind of prayer which “smites ones enemies.” It is good to understand and to be informed.

This kind of prayer sets one against the other. Nothing to do with healing or understanding. Thanks again. Very helpful.