In 2004 and 2008, South African president Jacob Zuma notoriously declared that his party, the African National Congress, will “rule until Jesus comes back.” The recent national election results favor his prediction, with the ANC winning its fifth national election since 1994.

In 2004 and 2008, South African president Jacob Zuma notoriously declared that his party, the African National Congress, will “rule until Jesus comes back.” The recent national election results favor his prediction, with the ANC winning its fifth national election since 1994.

To outsiders, the audacity of President Zuma’s statement can seem puzzling. The truth is that the ANC has managed to win election after election since 1994 because it continues to be seen by the majority of citizens as the political organization that ended apartheid, the party of heroic leaders like Nelson Mandela, and the party of black liberation and freedom. However, this narrative is becoming more complex, in part because new stories of discontent and resistance are emerging. In fact, the real surprise this election season was not the ANC’s victory, but rather the increasing number of black opposition voices who leveled stinging moral critiques at the ANC. Moreover, religion dramatically re-entered the political sphere. Critics deployed religious rhetoric in the service of radical leftist politics, and religious leaders embarked on protest campaigns aimed at holding the ANC (rather than the apartheid government) accountable, prompting President Zuma to assert: “bishops and pastors are there to pray for those who go wrong, not to enter into political lives.”

Certainly, religion has not been absent from politics over the last twenty years. Because the majority of black South Africans identify as Christian, churches frequently attract the attention of ANC leaders, especially during election season. But compared with heightened mobilization under apartheid, the noticeable political withdrawal of Christian churches and other religious bodies since 1994 has been a constant source of anxiety for progressive clergy and theologians. During the course of my fieldwork, I have heard many religious activists express frustration about the complacency of religious institutions in comparison with the “prophetic” role that religiously-affiliated organizations like the South African Council of Churches played during apartheid.

This election season, however, saw religious leaders from all sectors, including those from evangelical, charismatic, and Zionist churches, increasingly comfortable speaking out against the ANC government. The issues of concern? Poverty, unemployment, violence, police brutality, corruption, labor rights, land distribution, education, racial inequalities, and the ever-rising gap between the rich and the poor. While linked to South Africa’s tortured past, the persistence of these problems also implicates the current ANC leadership. For example, in an incident reminiscent of apartheid era violence, 34 striking miners were shot dead by police in 2012. The “Marikana Massacre” shocked the nation and the world, but to date no one has been held accountable for the decision to use lethal force.

Shocking events like Marikana help explain why founding Barney Pityana, black liberation theologian and member of the Black Consciousness Movement, lent his public support to the “Vote No” campaign, which encouraged the public to vote against the African National Congress in protest. In a scathing opinion piece, Pityana wrote, citing Hannah Arendt, that “South Africa under the Zuma ANC has all the makings of a descent into an authoritarian one-party state.” With crime and corruption rising, Pityana reminded his readers that “the overwhelming victims of this state of insecurity are the poor, women and black people.” For Pityana, the ANC has failed to create a compelling vision of transformation and instead pushed the poor into greater dependency and dehumanization. He goes on to suggest that the ANC has systematically undermined “the vision of a new South Africa” founded on values of human dignity, equality, and social justice.

I was particularly struck by the high level of political activity that took place in churches, or that involved clergy, over Easter weekend. This weekend proved an opportune time for activism because it fell just prior to Freedom Weekend, when the country celebrated twenty years of democracy, just two weeks before the national election on May 7, 2014.

In Durban, the ecumenical Diakonia Council of Churches used its annual Good Friday service to demand that “things must change.” Citing inequality, greed, violence, poverty, and corruption, over 3,000 people marched to City Hall. The tone of the day’s address mirrored that of the 1980s. Participants were called to confront “the powers” of this world and encouraged not to “lose sight of the real choices to be made.”

On Easter Saturday, April 19, Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town emeritus Desmond Tutu and current Archbishop Thabo Makgoba, along with Jewish and Muslim leaders, marched to Parliament in a “Procession of Witness.” The procession saw a wide range of ecumenical and inter-religious support, once again recalling anti-apartheid activism of the 1980s. The aim of the march was to send a direct message to President Zuma and the ANC. In his statement, Archbishop Makgoba called on political leaders to “live up to the national values established by the Constitution.” He further asked those with influence and power to “return to Nelson Mandela’s way of governance and leadership”—a style not threatened by social debate and mindful of the marginalized. Makgoba’s words gesture towards two widespread critiques of the “ruling” party: its autocratic leadership and neoliberal economic policies, both perceived to be at odds with Nelson Mandela’s vision of a democratic and transformed South Africa. Perhaps most significant was a public confession that faith communities had lost sight of their moral responsibilities to the poor and remained silent for far too long.

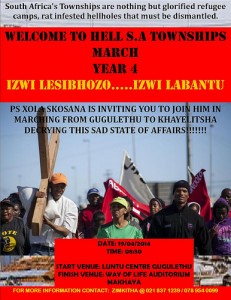

Occurring on the same day, Pastor Xola Skosana of Way of Life Church organized his own march called “Welcome to Hell – SA Townships.”

The march, based on an “out of body” vision Skosana says he received, is now in its fourth year. Skosana has made it his life’s mission to draw attention to what he calls the “gruesome violence of township life.” Townships are residential areas originally designed to provide racially segregated labor to urban centers. Many townships have large sections of middle class homes, but overcrowded living conditions and lack of sanitation remain the norm. Skosana does not mince words about the current state of affairs:

“Townships are nothing but glorified refugee camps, rat infested hellholes that must be exposed for what they really are. In many parts of South Africa, townships exist as readily available hubs of cheap labour to keep labour intensive industries going for the benefit of the few. Let it be known across the breath and length of this country that the continuation of separate development, and integration based on affordability, is the perpetuation of the notorious Group Areas Act of yesteryear.”

This is not the first time Skosona has used controversial tactics to draw attention to the plight of the poor. In 2011, he went on a month-long hunger strike. The march began in the township of Gugulethu and ended in Khayelitsha, both near Cape Town. Throughout the 11.5 K march, Pastor Skosana carried a large wooden cross.

While much smaller than the “Procession of Witness,” the “Welcome to Hell” march is especially noteworthy because it attracted the support of a newly formed political party—the Economic Freedom Fighters. Formed by expelled ANC youth leader Julius Malema, the EFF views itself as a “revolutionary” movement in the tradition of Frantz Fanon and Steve Biko. Known for their red berets and militant discourse, its supporters have been instrumental in provoking national debate about economic policies that continue to favor white elites. Their agenda includes land redistribution without compensation and the nationalization of all mines. Although their message is directed towards the poor, many middle-class black South Africans and intellectuals are also attracted to their urgent call for social change. The EFF received over a million votes this year, an impressive showing for the renegade party, making it now the second largest opposition party in South Africa.

While much smaller than the “Procession of Witness,” the “Welcome to Hell” march is especially noteworthy because it attracted the support of a newly formed political party—the Economic Freedom Fighters. Formed by expelled ANC youth leader Julius Malema, the EFF views itself as a “revolutionary” movement in the tradition of Frantz Fanon and Steve Biko. Known for their red berets and militant discourse, its supporters have been instrumental in provoking national debate about economic policies that continue to favor white elites. Their agenda includes land redistribution without compensation and the nationalization of all mines. Although their message is directed towards the poor, many middle-class black South Africans and intellectuals are also attracted to their urgent call for social change. The EFF received over a million votes this year, an impressive showing for the renegade party, making it now the second largest opposition party in South Africa.

Perhaps the most shocking challenge to the ANC came on Easter Sunday, when Bishop Barnabas Lekganyane, the main leader of the Zionist Christian Church, appeared to use his sermon to encourage millions of members to vote against the ANC. Though the ZCC is often considered apolitical because of its emphasis on African self-reliance, its massive Easter service occupies a special place in South Africa’s political landscape. Nelson Mandela delivered a rousing Easter address in 1992, and President Zuma was an invited guest of honor in 2012. In this year’s sermon, the Bishop urged members to elect “smart and intelligent” leaders who do not “confuse public funds” with their own. This can be interpreted as a double swipe at President Zuma, who is often derided for his lack of formal education and has been accused of corruption. A recent report by Public Protector Thuli Madonsela found that President Zuma improperly used public funds for a $25 million dollar upgrade to his private Nkandla estate—all while unemployment hovers at 25 percent.

As a result of this report, Madonsela gained recognition from Time magazine as one of the world’s 100 most influential people. The profile praised her “ability to speak truth to power and to address corruption in high places.” But her office has become the site of intense spiritual struggle. An unknown group called the Concerned Pastor Organization sought to cast out the “demons” in her office, prompting statements of condemnation from the Evangelical Alliance of South Africa and Archbishop Thabo Makgoba. Religious leaders in Cape Town, including Desmond Tutu, also held a silent protest in support of the Public Protector’s Office and her Nkandla report.

The resurgence of dramatic and symbolic forms of protest in South Africa, and the active presence of religious leaders in the public sphere, underscores the complexities of postcolonial “liberation” in one of the most unequal societies in the world. While ghosts of apartheid and colonialism continue to haunt, new specters of repression loom on the horizon.

In response, a renewed emphasis on moral and political struggle by religious leaders and activists suggests that the principles of anti-apartheid activism are increasingly being recalibrated for a post-Mandela era. In a public message on Facebook, posted on Good Friday, resident ideologue and EFF leader Andile Mngxitama shared a message from a follower: “We remember Jesus the communist who walked into the temple and unleashed an armed struggle on the exploiters!” This sounds not too different from the statement made by Black Consciousness activists on trial in 1973, when Jesus was named “the first freedom fighter to die for the oppressed.” Whether Jesus, the armed communist, will be a rallying cry in the future remains to be seen. What is clear, however, is that Jesus no longer simply serves as the ANC’s election barometer. The fact that those once heralded as liberators are now considered exploiters will certainly have political reverberations for years to come.