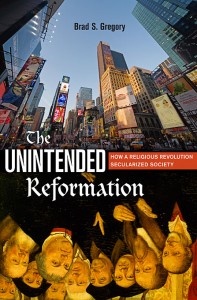

Over at The New Republic, Mark Lilla reviews historian Brad S. Gregory’s latest book, The Unintended Reformation: How a Religious Revolution Secularized Society. Placing the book firmly in the context of historical narratives, particularly Catholic historiography, Lilla argues that the book is not a pure work of historical analysis:

Over at The New Republic, Mark Lilla reviews historian Brad S. Gregory’s latest book, The Unintended Reformation: How a Religious Revolution Secularized Society. Placing the book firmly in the context of historical narratives, particularly Catholic historiography, Lilla argues that the book is not a pure work of historical analysis:

AFTER VIRTUE IS NOT an academic work of history and does not pretend to be. It is a strong work of advocacy that ends with a prayer. The same is true, alas, of Brad S. Gregory’s huge, and hugely frustrating, new book, which seems to have been inspired by [Alasdair] MacIntyre’s example. The difference, though, is that Gregory would have us believe that he is writing conventional history. A first glance at his wide-ranging chapters on post-Reformation developments in philosophy, politics, education, economics, and civil society, supplemented by 150 pages of rich footnotes, would incline you to believe him. Ecstatic blurbs from distinguished historians who should know better reinforce the impression. But the deeper you delve into this book, the more you begin to feel that you are watching a shadow-puppet play on the wall of some Vatican cave. A straightforward history of the post–Reformation West written from an explicitly Catholic standpoint would have been a welcome addition to our understanding of the period and of ourselves. Instead, Gregory has offered up a sly crypto-Catholic travel brochure for The Road Not Taken.

The book’s aim, he tells us, is to explain “how Europe and North America today came to be as they are.” (After the book’s second page contemporary Europe is hardly mentioned, making this yet another Americano history of “the West.”) And how do we live now? Not well. Gregory worries that our political life is polarized, that economic greed and mindless consumerism are idealized, that environmental degradation is accelerating at an alarming rate, that standards in schools are declining, and that public discourse is governed by ideological correctness and cultural relativism. And who doesn’t worry? But for Gregory these vast and various problems have a single source: the “hyper-pluralism” of modern societies. This term appears with metronomic regularity here, modified by a slew of adjectives like “never-ending,” “confusing,” “unintended,” “unwelcome,” “gangrenous,” and “hegemonic.” In an Agnew-esque moment he even complains of “pullulating pluralism.” “All Westerners,” Gregory declares at one point, “live in the Kingdom of Whatever.”

Read the full review here.