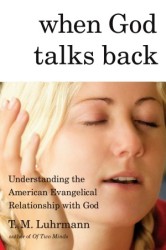

In The New Yorker, Joan Acocella gives a favorable review of Tanya M. Luhrmann’s When God Talks Back: Understanding the American Evangelical Relationship with God. The reviewer characterizes the book as a generous, albeit skeptical, inquiry into “what is going on in evangelical churches,” grounded in two years of fieldwork in Vineyard churches in Chicago and Palo Alto:

In The New Yorker, Joan Acocella gives a favorable review of Tanya M. Luhrmann’s When God Talks Back: Understanding the American Evangelical Relationship with God. The reviewer characterizes the book as a generous, albeit skeptical, inquiry into “what is going on in evangelical churches,” grounded in two years of fieldwork in Vineyard churches in Chicago and Palo Alto:

Luhrmann warns us against calling the evangelicals’ visions and voices “hallucinations”; that is a psychiatric and, hence, pathologizing term. In her vocabulary, such events are “sensory overrides”—sensory perceptions that override material evidence. She cites evidence that between ten and fifteen per cent of the general population has had such experiences. And she reports a vision of her own, which she had while working with the English witches. One morning, she woke up and saw six Druids looking at her through her window. (She lived on an upper floor.) In a moment, they were gone, and that was the only vision she ever had, but she has no doubt that she truly saw them. …

But Luhrmann’s primary justification of the evangelicals is what she describes as the huge amount of work they do. “Coming to a committed belief in God was more like learning to do something than to think something,” she writes. If all these people had to do was believe something new, that would be easy. Instead, they have to teach their brains to work in a new way. Sunday service is only one training ground. They go to house group; they attend conferences and retreats. They read devotional books. They pray and pray. (Sometimes you wonder how they manage to hold down jobs.) Their progress is slow and halting. Luhrmann places great emphasis on the hours that they put in, and I think that is not only because this is important to them but because she expects that it will be important to the reader’s view of them. Americans respect hard work.

Read the full review here.

See also this reflection by Luhrmann, published at Frequencies, on the practice of anthropological research.