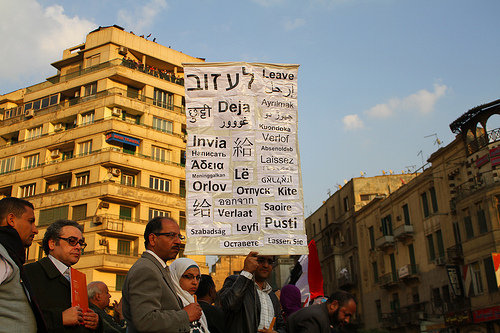

When Egyptians, on February 11, forced President Hosni Mubarak to step down, President Obama said that it was one of those rare moments when “we have the privilege to witness history taking place.” The issue that widely held sentiment raises for me concerns our responsibility in witnessing history, and how we contribute to “making history,” or to undermining those who are making it. History takes place over time, arising out of what people do or fail to do, and the people who make it are not only those immediately involved. The American Revolution was a tentative rebellion when it started, and it could have failed or succeeded, just like what is happening now across the Arab world. There was nothing inevitable or exceptional about the beginning or the outcome of the rebellion in the North American colonies of the British Crown until, over time, it became a Revolution, partly because of what others did to support the rebels. With the current events in the Arab world, what others do or fail to do will probably influence their course even more than in the case of the American Revolution. And present-day Americans bear particular responsibility for helping Arab rebellions become revolutions, because of the constant political intervention and frequent military incursions of the United States in the region.

When Egyptians, on February 11, forced President Hosni Mubarak to step down, President Obama said that it was one of those rare moments when “we have the privilege to witness history taking place.” The issue that widely held sentiment raises for me concerns our responsibility in witnessing history, and how we contribute to “making history,” or to undermining those who are making it. History takes place over time, arising out of what people do or fail to do, and the people who make it are not only those immediately involved. The American Revolution was a tentative rebellion when it started, and it could have failed or succeeded, just like what is happening now across the Arab world. There was nothing inevitable or exceptional about the beginning or the outcome of the rebellion in the North American colonies of the British Crown until, over time, it became a Revolution, partly because of what others did to support the rebels. With the current events in the Arab world, what others do or fail to do will probably influence their course even more than in the case of the American Revolution. And present-day Americans bear particular responsibility for helping Arab rebellions become revolutions, because of the constant political intervention and frequent military incursions of the United States in the region.

Thomas Farr, in his recent post, links the mass protests in the Arab world, combined with the persecution of Christian minorities in the region, and what he called “the Obama administration’s striking indifference to America’s statutory policy of advancing international religious freedom.” In my view, if the Obama administration is to do anything with respect to the International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA), it should seek to repeal it and to dismantle the whole policy and institutional structure that it entails, because this statutory policy is an insult to and betrayal of victims of human rights violations throughout the world, including Christian minorities in the Arab world. As I argued earlier, “Religious freedom can neither be advanced in isolation of other fundamental human rights nor sustained by imperial imposition.” Farr recalls that I, among others, strongly oppose the IRFA, but he does not respond to the reasons I gave for my position.

In this post, I will attempt to clarify my position by offering a historical view of how our celebration of what we now call the American Revolution requires us to support the maturation of what are now “mass protests” into the Arab Revolutions. The primary role in that process must be that of Arabs themselves, with each society acting in its own context. But the role of citizens of the United States is a matter of individual personal responsibility, because it is immediately connected to our attitudes and behavior. To the question posed in Thomas Farr’s title—“Where lies wisdom, where folly?”—I say that the universal measure is always the Golden Rule: Do unto others what you would have them do unto you. My strong opposition to the IRFA reflects my opposition to the United States’ failure to uphold the Golden Rule in its foreign policies. If the United States wishes to preach to others the imperative of protecting human rights, it must first apply that injunction to itself. My point is not that civil rights are violated in the United States, though there is sufficient reason for concern on that count; rather, the point is that domestic respect for the civil rights of citizens is not the same as the protection of human rights for all human beings equally, by virtue of their humanity and not their status as citizens. The United States does not have the moral standing and political legitimacy to uphold human rights anywhere in the world, unless it is willing to be judged by the same standards that it claims to apply to others.

I speak here of the official and consistent policy, commonly referred to as the Bricker Amendment of 1953, of not ratifying any human rights treaty that would require changes in the laws and practices of the United States. The unmitigated folly of this policy is that the United States claims the right to tell other countries to change their laws and practices to conform with human rights standards when it has officially and publically declared that it will never do so itself. It is ironic, also, that the United States refuses to do so, when it has less reason to fear being found at fault than many states that have been willing to submit to judgment according to international human rights standards. Freedom of religion must be protected everywhere, not because it is “America’s ‘First Freedom,” as Thomas Farr calls it, but because it is one fundamental universal human right among others. Wisdom, for the United States, lies in being part a global joint venture to protect human rights, and folly lies in the pretension to dictate to others what it is not willing to apply to itself. It is this utterly untenable position that I called “the ‘White Man’s Burden’ to civilize the rest of humanity,” which Thomas Farr found to be a “highly provocative charge.” Incidentally, this phrase was coined by the English poet Rudyard Kipling in reference to the imperialist venture of the United States in the Philippine Islands in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

As to the title of this post, history is what individual people do or fail to do, especially in purportedly democratic states like the U.S. What the Obama administration or Congress do or fail to do cannot be disassociated from the attitudes and behavior of the citizens of the United States. My title is meant to emphasize that it is because of the success of the American Revolution over time that citizens of the United States can now change the policies of their country to a greater extent than Arabs are able to, at least in the short term. My point is not that Arabs are helpless victims who must wait for the United States to save them from their regimes; rather, the issue for me is our responsibility in making or changing the policies of the United States here and now, regardless of what Arabs or any other people can do for themselves in their countries.

In my view, our failure to support the capacity of Arabs to do what we take for granted will doom the American Revolution to failure over time. To briefly explain what some readers may find too provocative an assertion, nothing human can be perfect, and all human achievements will diminish and eventually come to an end. Just as it has evolved since its inception, the United States, as the outcome of the American Revolution, will also end in time. There will be a time when there is no United States, though people will continue to live and, I hope, thrive in this part of the world. How soon and complete the decline and fall of the United States will be depends on our ability to uphold the values and actions that sustain this political experiment in its historical context. It is also important to recall here that both the rise and fall of the United States, like any other human process, unfolds over time, that is, in history. So, the fact that we don’t see the demise of the United States as imminent does not mean that it is not in the process of happening. In fact, it is bound to happen, as with all things human.

In my view, our failure to support the capacity of Arabs to do what we take for granted will doom the American Revolution to failure over time. To briefly explain what some readers may find too provocative an assertion, nothing human can be perfect, and all human achievements will diminish and eventually come to an end. Just as it has evolved since its inception, the United States, as the outcome of the American Revolution, will also end in time. There will be a time when there is no United States, though people will continue to live and, I hope, thrive in this part of the world. How soon and complete the decline and fall of the United States will be depends on our ability to uphold the values and actions that sustain this political experiment in its historical context. It is also important to recall here that both the rise and fall of the United States, like any other human process, unfolds over time, that is, in history. So, the fact that we don’t see the demise of the United States as imminent does not mean that it is not in the process of happening. In fact, it is bound to happen, as with all things human.

The Golden Rule is also instructive in regard to the obsession of political and opinion leaders, the media, and the U.S. public at large with the risk of the Muslim Brotherhood coming to power in Egypt and other countries in the Arab world. The unstated premise and conclusion of this obsession seems to be that we should not support democratization in the Arab world if the likely or even remotely possible outcome is the coming of “Islamists” to power in this strategically vital region for “American interests.” Although I am not able to prove my claim, I am confident that a very similar discourse was current in Britain at the time of the American Revolution. The imperial elite of Britain must have been worried about the negative impact of the American Revolution on their interests, without any consideration of what that Revolution meant for the freedom and well-being of the American revolutionaries and their society.

Let me try to explain further, in the hope of minimizing the risk of miscommunication, which is particularly serious when we deal with profound transformations that challenge our deeply held assumptions and prejudices. I personally am opposed to the Muslim Brothers and have struggled to challenge their views of Islam and politics since the 1960s. Their ideological confusion and devious politics have caused horrendous loss and pain in my home country, Sudan. I therefore have no illusions about the serious costs of their coming to power anywhere, especially in a country like Egypt. My concern, however, is how to effectively confront and combat that risk, because I realize how serious it is. This is not an attempt to downplay the drastic implications of the Muslims Brothers coming to power. But it is from this perspective that I call for unconditional commitment to equal liberty for myself and others, especially those who disagree with me. In fact, I am free only to the extent that my opponents are free. My friends do not need this commitment from me, because they have my love and support. It is my opponents who need my principled commitment. My primary focus here is on what Muslim societies need to do for themselves and for their own reasons, regardless of what the United States wants or needs.

The primary task of sustainable democratization and protection of human rights throughout the Muslim world is for local populations to expose and challenge the myth of an Islamic state—to realize that Sharia cannot, ever, be enforced by the state. When Sharia is enacted as state law, it becomes the secular political will of the state and not the religious law of Islam. Muslims must realize that a secular state is a necessary condition of the possibility of a Muslim person and society. It is equally clear, however, that only Muslims can do this by and for themselves, within their own societies. This is the only morally legitimate and politically viable source of democracy and self-determination. The failure of the United States to stand by this principle in the case of the Arab Revolution is a betrayal of the values of the American Revolution. It can also be reasonably argued that such “conditionality” of support for democratic transformation, dependent on the exclusion of the Muslim Brotherhood, is a pretext for continuing neocolonial political domination and economic exploitation of the Middle East.

The Muslim Brotherhood is a coalition of social, religious, and political movements, which can assume a variety of organizational forms and operate through a range of strategies. Whether they operate openly and legally through “front” organizations or are forced to work underground, their religious and ideological appeal has several sources. One source, for instance, is their ability to present themselves as the “true voice” of their communities, the “authentic” expression of their people’s right to self-determination. More concretely, they have been able to present themselves, until very recently, as the legitimate and effective alternative to corrupt and oppressive regimes, like that of Mubarak in Egypt or bin Ali in Tunisia. Another source of legitimacy is their appeal to romantic and simplistic notions of Islamic history, as if it were a computer “software” program that present-day Muslims could simply “install and run” as a panacea to all of the social, political, and economic problems of the post-colonial condition. Moreover, Islamists thrive under conditions of political repression, because of their ability to operate through mosques and “Islamic centers,” while benefiting from popular sympathy as “victims” of secular oppressive regimes. As we have seen through decades of experience, in the Arab world in particular, Islamists tend to blame the lack of democratic freedoms for their failure to explain clear and specific programs for socio-economic and political reform.

In other words, having to operate under oppressive conditions enables them to continue to speak in vague, emotional terms about their being the “obvious and natural” alternative, without having to explain what they intend to do and how. As these and other possible factors clearly show, the response to the risk of Islamists coming to power in the Arab world must begin by allowing all Islamists, including the Muslim Brothers of Egypt, to operate legally and openly, in free and fair competition with all other political forces in the country. Ensuring democratic governance and protection of human rights for Islamists is the only way to expose and defeat their confused ideology and dangerous politics. As we have seen in the case of Hamas in Gaza, conditional support for democratic transition is counterproductive, because it enhances the perceived legitimacy and political efficacy of Islamists in their own societies.

It is therefore clear that both principled and pragmatic reasons unite in urging unconditional support for democratization, regardless of narrow, short-term calculations of the risks it may pose to our interests. After all, Muslims are by far the primary victims of Islamist violence and authoritarianism. Terrorism is a human problem, not an American or Western problem. In the same way that Israel remains democratic under constant threats to its very existence, Arabs states can and should be democratic despite the risks of Islamist politics. If Islamists come to power in any country, we will deal with that reality, just like the people of the country have to deal with it, though with fewer resources than we have and greater potential cost to their societies than we will have to cope with. In the final analysis, this is the only way to individual freedom, social justice, and sustainable political stability.

I think Professor An-Na’im gets this exactly right. The way to foster democratic reform around the world is not with military intervention, which usually causes as many problems as it solves, but its opposite—tending one’s garden at home, and supporting real religious freedom abroad, not simply the kind that we like. In my view, President Obama is not doing a bad job following this advice—perhaps not as forcefully as An-Na’im would like, but then the domestic political scene hardly allows him to openly tout the idea of a reformed Brotherhood. His opponents would call him terribly naive, and time could prove them terribly right. Better the circumspect path Obama has taken, uninspiring as it may be. Still, one hopes that some of what An-Na’im says here is being absorbed by the administration (and I think it is): only religious freedom that allows questionable opinions a place in the public sphere (as appears to be happening in Turkey) will produce real civil society in the Arab-Islamic world. What An-Na’im, perhaps politely, does not say, is that as a result, American foreign policy will need to take a much more even-handed approach to Israel: we cannot continue propping up the Mubaraks and the House of Saud indefinitely simply because Israeli settlers want more more living space.