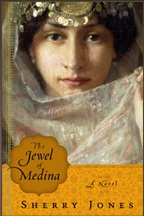

The Jewel of Medina, written by Sherry Jones, is a fictionalized account of the life of A’isha, youngest wife of the prophet Muhammad. The book was dropped by Random House for fear of a fundamentalist backlash, picked up by a British publishing house whose main publisher subsequently had his home office firebombed, and has finally been published in the US by Beaufort Books. Without having read it people have been offended by its content, while others have defended Jones’ First Amendment right to freedom of speech.

The Jewel of Medina, written by Sherry Jones, is a fictionalized account of the life of A’isha, youngest wife of the prophet Muhammad. The book was dropped by Random House for fear of a fundamentalist backlash, picked up by a British publishing house whose main publisher subsequently had his home office firebombed, and has finally been published in the US by Beaufort Books. Without having read it people have been offended by its content, while others have defended Jones’ First Amendment right to freedom of speech.

Is the book controversial? Yes. Is it any good? In the vein of all historical romance, no. But what repeatedly comes up as troubling are the glaring historical inaccuracies and misrepresentations of Islam. From the New York Times review:

Jones alters early Islamic versions of A’isha’s life—the first of which was written 150 years after Muhammad’s death—in relatively few aspects. She transforms A’isha into a sword fighter. She makes her a precocious military strategist. She depicts her kissing a man she was briefly engaged to prior to Muhammad, her accused partner in the adultery episode. The record doesn’t mention kissing, and the man was not engaged to A’isha. Jones also inserts a Turkish custom—the choosing of a harem’s premier wife, or hatun—unknown in seventh-century Arabia.

…An inexperienced, untalented author has naïvely stepped into an intense and deeply sensitive intellectual argument. She has conducted enough research to reimagine the accepted versions of Muhammad’s marriage to A’isha, thus offending the religious audience, but not nearly enough to enlighten the ordinary Western reader. Should free-speech advocates champion “The Jewel of Medina”? In the American context, the answer is unclear. The Constitution protects pornography and neo-Nazi T-shirts, but great writers don’t generally applaud them. If Jones’s work doesn’t reach those repugnant extremes, neither does it qualify as art.

At Red Room, G. Willow Wilson, a Muslim who has been outspoken in supporting Jones’ right to publish this book, has similar critiques:

Jewel’s historical inaccuracies follow a pattern particular to the portrayal of eastern cultures in western literature. They are not of the Braveheart variety—a few locations here, a few events there, a made-up love story or two. In Jewel, the protagonist Aisha is confined to the house after her engagement, in a practice known as purdah. It is one of the seminal events of the story’s first act. Purdah is a tradition that originated among the Hindus of the Indian subcontinent. Not only is there no concept of purdah in Arabia, there is no letter ‘P’ in Arabic. The word itself cannot be written in the language the characters are theoretically speaking. Later, Aisha becomes part of a systematized harem, in which wives hold titles and distinct ranks. This system was an invention of 15th century Turkish sultans, and would probably have scandalized the original Arab Muslim community.

That may mean nothing to you, so let’s get back to Braveheart. Here’s a comparable historical disparity: it’s as if a cadre of Spanish conquistadors were to show up with their guns to help William Wallace fight the British. Not to be outdone, the British bring in a phalanx of Spartan warriors, who, unprepared for the cold weather, declare an Olympic peace and throw javelins around until summer. If you were to read that in a book, you would probably close it with an exclamation of disgust and put it away. So it should come as no surprise that this was the first impulse of many Muslims.

Read the full New York Times review here, and the full Red Room review here.