Samuel Moyn’s essay, “Personalism, Community, and the Origins of Human Rights,” makes an important contribution to our understanding of the history of the concept of human rights. I am a philosopher. Though I have a considerable interest in history, I am not a historian. Before reading Moyn’s essay I knew nothing about the developments that he discusses. Discovering the depths of my ignorance might have left me feeling embarrassed and chagrined but for the fact that, as Moyn observes, almost none of his fellow active historians knew anything about these developments either.

Samuel Moyn’s essay, “Personalism, Community, and the Origins of Human Rights,” makes an important contribution to our understanding of the history of the concept of human rights. I am a philosopher. Though I have a considerable interest in history, I am not a historian. Before reading Moyn’s essay I knew nothing about the developments that he discusses. Discovering the depths of my ignorance might have left me feeling embarrassed and chagrined but for the fact that, as Moyn observes, almost none of his fellow active historians knew anything about these developments either.

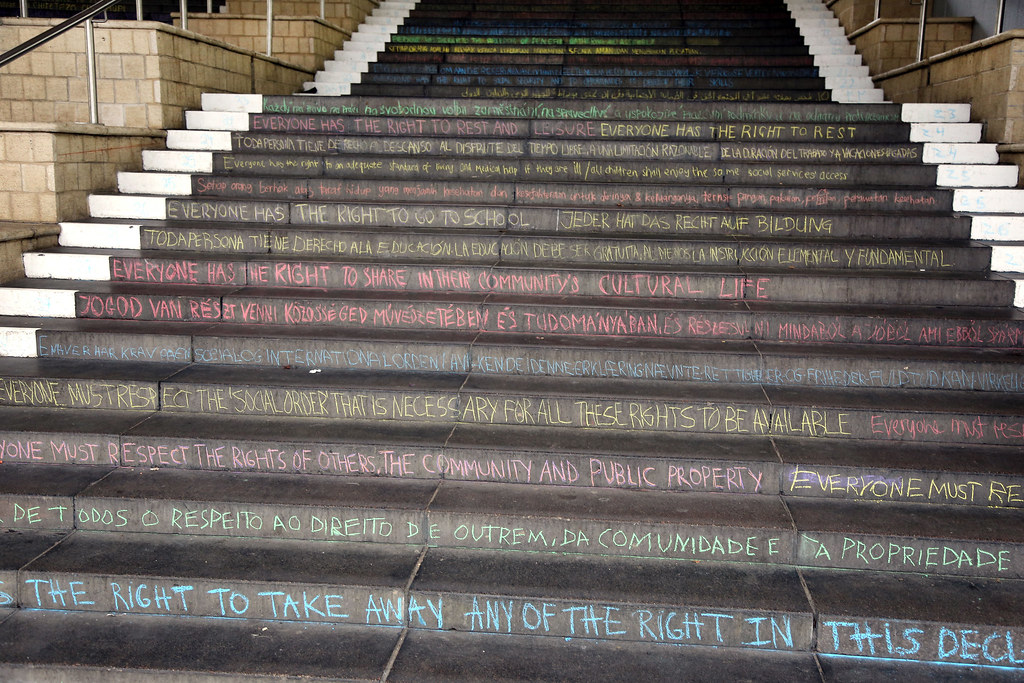

Moyn’s essay explained something that has puzzled me for some time: many things that the United Nations declarations cite as “human rights” do not even come close to satisfying the concept of human rights that philosophers customarily work with. Philosophers typically explain a human right as a right such that the only status required for possessing the right is that one be a human being—not any particular kind of human being, just a human being. Different philosophers formulate the idea somewhat differently; but I think it’s fair to say that’s the core idea.

Article 23 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights says, “Everyone has the right to work.” To have this right, one must be capable of working. Many human beings are not capable of working, Alzheimer’s patients, for example. In not being given work, they are not deprived of something to which they have a right. Article 24 of the Universal Declaration says, “Everybody has the right to…periodic holidays with pay.” In many societies there is no such thing as paid holidays. Members of those societies are not wronged by not being offered paid holidays.

I have, on occasion, wondered why there is this discrepancy between the concept of human rights that philosophers work with and the lists of human rights given by the UN declarations. I have speculated that perhaps the authors of these declarations did not have their eyes on the rights one has just by virtue of being a human being but on the rights one has by virtue of being capable of functioning as a full-fledged person in a modernized society? But if so, why?

I think I now have the answer. Moyn shows that the immediate background to the UN declarations was the discussion of human rights that emerged in the 1930s and 1940s within the context of the religious-philosophical movement known as personalism, and that the appeal by the personalists to human rights was designed to fend off the twin modern dangers of collectivism and individualism. Given that background, it’s entirely understandable that their focus was on the rights of full-fledged persons in modernized societies.

A question that Moyn’s discussion does not answer is this: given the tight connections that the personalists drew among persons, dignity, and rights, what status did they give to those human beings who are not capable of functioning as persons—those in a permanent coma, those sunk deep into Alzheimer’s, infants? Do such human beings lack dignity and hence not have rights? I myself think that understanding the rights of human beings who are not capable of functioning as persons poses one of the most important challenges to theories of rights.

In my own thinking and writing about rights, my guiding interest has been systematic rather than historical; and it has been the rights in general of human beings that have interested me, not just that special set of rights that we call “human rights.” My aim has been to develop a theory of rights in general. Though my main interest has been systematic, I did incorporate into my analysis some discussion of the history of the concept of rights. I did that because I found that, when speaking and writing about rights, listeners and readers regularly confronted me with the narrative which says that the concept of rights was devised by the individualist philosophers of the secular Enlightenment and that it cannot be lifted out of that context and placed into some other.

But it was, and remains, my view that rights have no intrinsic connection to individualism. A right, as I see it, is a legitimate claim to being treated a certain way that would be a good thing in one’s life; rights are inherently social. That said, someone who is a “possessive individualist” in his orientation will often ignore the legitimate claims of others concerning how he should treat them and focus only on his own legitimate claims concerning how they should treat him. But that is morally perverse.1Let it be noted that the concept of rights is by no means the only moral concept that is commonly abused.

One way to make the point that rights have no intrinsic connection to individualism is to articulate and defend an understanding of rights for which that is clearly the case. I did that in my book, Justice: Rights and Wrongs. Another way to make the same point is to find an example of the concept of rights being employed by thinkers and writers whose orientation is clearly not individualistic. Had Moyn’s essay been published when I was thinking and writing about these matters some eight years ago, I could have used the history that he has unearthed to do so: the personalists were explicit and vigorous in their opposition to individualism. But Moyn’s essay had not yet appeared. It was my good fortune, however, that Brian Tierney’s book, The Idea of Natural Rights, was published in 1997, followed shortly by Charles Reid’s Rights in Thirteenth-Century Canon Law, a doctoral dissertation that Tierney supervised. What Tierney and Reid show, beyond a doubt, is that the canon lawyers of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries were employing the concept of rights, and that among the rights they identified were a good number of those that we now call “human rights.” Then, in 2007, came John Witte’s book, The Reformation of Rights: Law, Religion, and Human Rights in Early Modern Calvinism. It turns out that the early Calvinist reformers also employed the concept of rights, and that a good many of those that we now call “human rights” were among the rights they identified.

In his article, Moyn writes: “Forgotten now, the spiritual and often explicitly religious approach to the human person was…the conceptual means through which Continental Europe initially incorporated human rights….” He further writes: “Indeed, human rights need to be closely linked, in their beginnings, to an epoch-making reinvention of conservatism. This defining event of postwar West European history is familiar from the more general historiography of the period in the form of Christian Democratic hegemony, but is absent so far from human rights history—even though this same Western Europe became the earliest homeland of the concept.”

These claims seem to me not correct; or to speak more precisely, they seem to me not to be the full story. Moyn notes that the English term “human rights” had very little currency before the early 1940s—though the term “rights of man” had been around for more than a century and a half. The canon lawyers of the twelfth century did not employ a Latin equivalent of either of these terms. They had our concept of rights; but they did not single out from rights in general the subset of human rights and conceptualize them as such.

What the canon lawyers did do, however, is identify and discuss a good many of the rights that we would now classify as human rights: the rights of the poor, the rights of aliens, etc. So too for the later Spanish theologians who defended the rights of the natives in South America, and for the early Calvinist reformers that Witte discusses: among the rights they identified were rights that are in fact human rights.

Thus there are two stories to be told about the recognition of human rights. One is the story of the introduction and employment of the concept of rights and the inclusion of what we would now call “human rights” among the rights identified. The other is the story of the singling out of that special subset of rights that we now call “human rights” and conceptualizing them as such. The former story is a long story, going back into the twelfth century; the latter story—a component within the former—is a shorter one. If I understand him, Moyn thinks it begins in the early 1940s. I think it begins considerably earlier.

The second paragraph of the US Declaration of Independence opens with the famous sentence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” The authors are here singling out for special attention and conceptualizing those rights that we now call “human rights.” They did not use our term “human rights.” They called them “unalienable rights that all men have.” Others at the time called them “the rights of man.”

Since the eighteenth century, the concept of human rights has been employed within a number of significantly different moral cultures and philosophical frameworks; the concept is not the “property” of any one culture or framework. Moyn has rendered us the service of bringing to light one of those forgotten frameworks—the personalism of the 1930s and 1940s. His explanation for why that framework has been forgotten is that Christianity, after having been woven into the fabric of personalism, suffered a precipitous collapse in Europe in the 1960s. He notes that theorists nowadays commonly set the concept of human rights within a Kantian framework.

The concept of rights in general has been employed across a much longer stretch of time and within an even larger number of significantly different moral cultures and philosophical frameworks. That seems to have been largely forgotten in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I have never come across an explanation of why Christians of that time no longer remembered the use of the concept of rights by canon lawyers, theologians, and philosophers of the medieval and Reformation periods. I look forward to the day when a historian explains this strange amnesia. I can understand why non-Christians had no interest in keeping the memory alive. But why did Christians forget this part of their heritage?

From Moyn’s essay, we learn that Jacques Maritain, in the early 1940s, shook off the common view that rights-talk is inherently individualistic and employed the concept of human rights within the framework of personalism. But we still do not know why. Did Maritain escape the common view because he had somehow recovered from the historical amnesia of his peers? Had he, for example, discovered that the canon lawyers of the twelfth century and the Spanish theologians of the sixteenth century not only employed the concept of rights but recognized as rights a good many of those that we now call “human rights”? Or was he, too, ignorant of those pieces of history? Was it perhaps his philosophy of personalism that led him to realize that rights-talk is not inherently individualistic? I still do not know the answer to these questions.