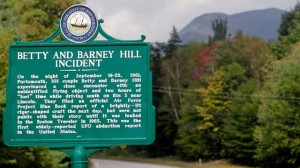

A friend recently sent me a Huffington Post piece from last summer on the state of New Hampshire putting up one of those road-sign historical markers to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the UFO abduction experience of the mixed racial couple, Betty and Barney Hill. The latter events began on a dark highway on the night of September 19, 1961, and then played out—via time-loss, magnetic car markings, nightmare, psychological suffering, psychiatric help, hypnosis sessions, and a journalist’s book—into America’s first major abduction report. A few days after I saw the photo of the road-sign featured in this piece (okay, and happily uploaded it onto my laptop as my new desktop image), I knew that I wanted to lead with this story and this image for my reflections on Frequencies. Why?

A friend recently sent me a Huffington Post piece from last summer on the state of New Hampshire putting up one of those road-sign historical markers to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the UFO abduction experience of the mixed racial couple, Betty and Barney Hill. The latter events began on a dark highway on the night of September 19, 1961, and then played out—via time-loss, magnetic car markings, nightmare, psychological suffering, psychiatric help, hypnosis sessions, and a journalist’s book—into America’s first major abduction report. A few days after I saw the photo of the road-sign featured in this piece (okay, and happily uploaded it onto my laptop as my new desktop image), I knew that I wanted to lead with this story and this image for my reflections on Frequencies. Why?

Because it signals that such extraordinary events are also part of real history; that they too deserve our attention, remembrance, and analysis; that they are not simply a function of cranks and frauds. The New Hampshire road sign is jarring precisely to the extent that it brings the impossible into conjunction with the utterly solid and banal—all that metal, all that paint, and all authorized by the official Seal of the State of New Hampshire. With its appearance, American history suddenly becomes much more interesting, more alive, and way weirder. I am delighted not because I am persuaded or convinced by the factuality of the sign’s iron presence or the matter-of-factness of its words, or, for that matter, because I “believe” anything at all (I don’t believe in belief). I am delighted because the sign functions as a historical marker, that is, as a recognition that something strange and uncanny happened there, on that same road, a little over fifty years ago.

Something.

As I read through the posts of Frequencies again, I am reminded of the impossible road sign up there in New Hampshire. Each post, after all, similarly functions as a sign that strange and uncanny things happen all the time to all sorts of people—automatic writing and poetic visionary experience, light sabers and mythical mashups, religious openings through sex and LSD, a new revelation channeled to a professional psychologist (at Columbia no less), six druids standing against an ethnographer’s window above a London street, and on and on and on. Really, we could do this for decades, no? Taken together, the entries make an utter mockery of any simple notion of religion. As if there were any. What there so obviously are, of course, are people. And people are different, really, really different.

Ah, you say, this is because of our postmodern, post-industrial, post-capitalist, or post-something-or-other culture. But no one who has taken a close and serious look at, say, the history of Hinduism or early Christianity can possibly believe that one. It seems much more likely that this is what religion is anywhere we look, if only we would look—a New Age marketplace, a mythical mashup, a collection of “wild facts,” as William James called psychical and mystical phenomena, or of wild talents, as Charles Fort called paranormal powers (“wild” being the key qualifier here). Sometimes a tradition is able to gather together a few of these wild facts and talents, shape them into something useful through myth, ritual, and art, and hold it all together for a time. But only for a time.

I suspect this most basic of observations—that things are wild and plural everywhere and everywhen we look—is also the most basic reason “the spiritual” is so resisted in conservative and traditional circles, be they religious, political, or academic. Basically, the category is code for “It’s way more complicated, and way simpler, than that.”

On the complicated side, the category is subversive to religious identity itself, any religious identity. And God only knows what it could do to our flatland histories, as if kings, presidents, nation-states, and religious institutions capture what really goes on in human history. I listen to the news each morning on the radio and think, “Really? This is really what I am supposed to identify as ‘what happened yesterday’ to all those billions of people? Really?” It’s all just completely ridiculous. There are other histories, much more important hidden histories that we have only begun to note and trace.

On the simpler side, it is not all wild buzzing and blooming, nor is it all hidden. Not at all. Indeed, these Frequencies posts reminded me again that scholars of religion know far more than we are often willing to admit, even if this “far more” is usually implicit and seldom, if ever, rendered explicit. We know, for example, that religious identity is constructed, like every other aspect of the ego. We know that religions are historical phenomena, constructed again by enough social, political, linguistic, cognitive, and biological processes to make anyone’s head spin. And—and here is the Big Simple One—we know that, wherever and whenever they are found, all religious experience shares one indubitable universal ground: human nature. So it’s all different, and it’s all the same. That is really complicated, and that is really simple. Can we hold these two in balance now?