Much more than a blog, Frequencies is a treasure trove of deep description and highly creative analysis. The casual observer initially might assume Frequencies to be a motley collection of unrelated reflections on matters ranging from historical figures to chicken sandwiches. Such an assumption could not be more foolhardy, however. The hundred essays that comprise Frequencies could not be more intimately related, as all of them, in their own ways, are part of the same family tree. In fact, Kathryn Lofton and John Lardas Modern intentionally describe Frequencies as “a collaborative genealogy of spirituality.” A close reading of the contents of Frequencies reveals just how apt this characterization is.

In The New Metaphysicals, Courtney Bender notes that defining spirituality is “like shoveling fog.” Indeed, a subject as intensely personal as spirituality tends to be subject to as many definitions as it has practitioners or adherents. And as Leigh Schmidt and other historians have shown, spirituality has appeared in myriad forms and meant many different things over many generations. Despite its resistance to concrete definition and operationalization, in its broadest sense the rubric “spirituality” has remained a decidedly steady component of the human condition. Thus “genealogy” seems an especially appropriate approach to Lofton and Modern’s effort to elucidate what spirituality is (and is not). Like any family tree, today’s manifestations of spirituality and its historical antecedents reach far and wide. Spirituality’s DNA also sometimes expresses itself in unexpected ways. As anyone who has tried to unearth information about his or her forebears can attest, much can be learned from discovering—or even from searching unsuccessfully—for the branches of a family tree.

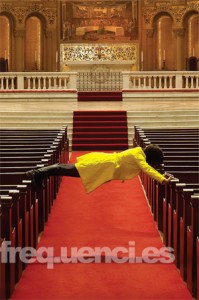

I also have been struck by the cleverness of Lofton and Modern’s self-presentation as “curators” of Frequencies, rather than editors or coordinators or some other boring, bureaucratic term. “Curate” is, of course, both a verb and a noun. Thus, Lofton and Modern have curated an art exhibition of sorts (in both content and form, with visual art accompanying each entry)—but even more profoundly, they have acted as curates, taking on responsibility for the care of souls. (I cannot resist noting that the World English Dictionary also lists “assistant barman” as an alternate definition of the noun “curate.”) Because spirituality embodies something so human and alive, it is eminently sensible that Frequencies should be presented in a soulful, considerate, and caretaking manner. In a meaningful sense, freq.uenci.es is akin to ancestry.com.

Lofton and Modern received contributions from observers ranging from senior academics to DJ Spooky. Their invitation called for “fragments in a dynamic, large-scale portrait” and was accompanied by a rather comprehensive list of potential topics. It is noteworthy in the context of genealogy that the contributors to Frequencies often chose to write about topics that diverged from the list provided by the curators, much like one often is surprised by discoveries about long-forgotten ancestors. I suspect that Frequencies offered similar surprises (and delights) to Lofton and Modern as their “large-scale portrait” developed. Frequencies is richer and truer because of the tremendous latitude afforded to its contributors; spirituality’s real family tree has been allowed to take shape.

Several entries are especially resonant (referencing another term carefully chosen by Lofton and Modern) with the notion of spirituality as profoundly connected with various understandings of family. Elijah Siegler’s entry titled “Automation” refers several times to the fact that unlike other academic subjects, “the word spirituality fills [him] with anxiety.” For me, this observation reflects all the worries so many people have about dealing with immediate family members, because, like studying spirituality, doing so often is fraught with complication. (I must note that Siegler’s hilarious book-title generator is well worth investigating as well.) Darren Grem’s lamentation on the “Chicken Sandwich,” as purveyed by the popular fast-food chain Chick-fil-A, emphasizes the very particularist (evangelical Protestant) spirituality underlying a highly profitable business. Chick-fil-A is so profitable that it retains a longstanding policy of closing on Sunday, a “decision [that] was as much practical as spiritual…. (A)ll franchised Chick-fil-A Operators and their Restaurant employees should have an opportunity to … spend time with family [emphasis mine] and friends.” In sharp contrast with the moral questions inherent in selling chicken sandwiches are Michael Gilmour’s observations about “Companion Animals.” As I write this with one of my feline family members asleep on my desk, Gilmour’s concluding remark resonates especially strongly: “For the nineteenth-century poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, all living things reveal the creator God, with each kingfisher and dragonfly—and let us add each companion animal—offering a glimpse of the divine.” And then there is Chip Callahan’s rendering of the “Highway,” that wonderful conduit of family road trips and maker of lifelong memories. In Callahan’s case, “In the summer of 1978 … my whole family packed into an Itasca motorhome and spent six weeks driving a loop around the country…. I was ten years old, and the trip … was discovery on multiple levels…. It was history and myth come alive as we drove, walked, and slept in places we’d [only] heard and read about.”

Family ties are bound up with a lifetime’s worth of anxieties, love, and memories—and with the loss thereof. So too spirituality is inextricable from how we deal with loss. Such themes appear again and again in Frequencies. We hear from Wendy Cadge about “Spiritual Care Services” in hospitals, whose “efforts are premised on the belief that everyone has some sense of spirituality that … chaplains can tap into and work with in their interactions with patients and their families [emphasis mine].” Sarah McFarland Taylor evokes the inherent sadness of an “Estate Sale,” at which she “did not expect the intimacy with which [she] would sift through peoples’ lives.” Various contributors to Frequencies grapple with the tension between spirituality and material items, but no one can deny the fact that the physical detritus of everyday life carries special meaning to the descendents of those who owned it—whether we want to preserve such items, sell them, or destroy them. Laura Marris offers two evocative poems under the heading “Loss,” both of which clearly allude both to loved ones and to the self in days gone by. The passage of a family member of a different sort is a theme of Pamela Klassen’s observations about Max Weber’s grave. Weber is a member of our collective academic family tree rather than our biological ones, and Klassen invites us to consider the memorial to him as well as the inherent spirituality of cemeteries in general.

In short, Frequencies goes a long way toward creating the “large-scale portrait” of spirituality that Lofton and Modern set out to assemble. The portrait is not defined by clean lines, but by a mixture of images and ideas. It is messy and surprising in a good way, as is any family tree. And for some reason Frequencies reminds me of one of my favorite moments in film: the closing scene of “A River Runs Through It.” This scene is glorious visually, musically, and spiritually, especially because it evokes the deeply personal complexity and pain of humans’ love for family. In the words of author and fly-fisher Norman Maclean, for whom a river is like the trunk of a family tree:

In the Arctic half-light of the canyon, all existence fades to a being with my soul and memories and the sounds of the Big Blackfoot River and a four-count rhythm and the hope that a fish will rise. Eventually, all things merge into one, and a river runs through it. The river was cut by the world’s great flood and runs over rocks from the basement of time. On some of those rocks are timeless raindrops. Under the rocks are the words, and some of the words are theirs. I am haunted by waters.