It is difficult to come to an agreement when normative issues are concerned. Are the “moderate” forms of European secularisms flexible enough to include the Muslim population as well, as Tariq Modood suggests? Or are they “irretrievably flawed,” as Rajeev Bhargava has argued, because they emerged from a context in which Christian confessions dominated and were not set up to include non-Christian minorities? Or should we get rid of the language of secularism altogether and instead refer to liberal-democratic constitutionalism as a meta-language, as Veit Bader has proposed?

It is difficult to come to an agreement when normative issues are concerned. Are the “moderate” forms of European secularisms flexible enough to include the Muslim population as well, as Tariq Modood suggests? Or are they “irretrievably flawed,” as Rajeev Bhargava has argued, because they emerged from a context in which Christian confessions dominated and were not set up to include non-Christian minorities? Or should we get rid of the language of secularism altogether and instead refer to liberal-democratic constitutionalism as a meta-language, as Veit Bader has proposed?

Such a debate can certainly help to confront our taken-for-granted assumptions with other perspectives: European religious liberties look different when compared with a multi-religious society like India (even if not explicitly mentioned in Bhargava’s paper) and its practices of accommodation and vice versa. And the participants in the debate obviously agree upon a common definition of the “problem” that Europe faces: namely to socially, legally, and politically integrate its ethnic and religious minorities, especially its Muslims.

But here the consensus comes to an end. I would say it necessarily comes to an end, because no ultimate proofs are available for value judgments. As value judgments they themselves are inherently “flawed.” What can help us to understand the conditions and to assess the consequences of certain forms of “secularism,” of state regulations on religion and related social institutions and societal practices, is comparative empirical research rather than the exchange of normative positions (or the substitution of normative concepts). Such research would have to be a common endeavor of scholars from different parts of the world. And it would imply that they take note of the research that is already available in a variety of languages, but has not been translated into English and therefore does not exist in the global discourse.

The problem of normative approaches is visible in the ongoing debate on the “crisis of secularism in Western Europe” as well. One of the problems is that the reality of the so-called “moderate” secularism(s) of Europe on the one side is compared to an abstract principle, called “principled distance,” on the other. Veit Bader has rightly pointed out—and Rajeev Bhargava would probably agree—that the practice of Indian secularism, which this principle relates to, is no less ambivalent than in the different cases of European secularisms, even if the problems are not the same everywhere. But then we would have to compare practices with practices rather than practices with principles. On top of that, more than one or two types of European secularism exist. Different traditions of secularism, secularity, and religion-state relations exist in Western Europe (not to mention in Eastern Europe), with different consequences in practice. Saying this does not neglect common concerns, the integration of migrants being one of the most eminent.

Another problem of value judgments is that concrete examples are usually given in order to support a claim instead of exploring the conditions and effects of a certain phenomenon. In a world where English has to serve as a substitute for the languages which we ourselves don’t speak (may they be Hindi, French, Arabic, Russian, German or any other language), we have to rely on volumes and articles in English that give us overviews on world-wide developments. However, the examples presented there do not always paint an accurate picture of the reality in different countries and regions. Sometimes this is due to a lack of information, sometimes it is because the primary interest in practices of discrimination does not always allow for differentiated perspectives and ambivalent results.

Even if Rajeev Bhargava is correct in his general statement that European countries (and their “secularisms”) have fundamental problems with including Muslims, he is not so in regard to some of his examples. I just refer to the German examples that he gives: Muslim private schools are indeed rare in Germany, but if they are acknowledged by the state, they do get state funding. For example, this is the case with a Muslim elementary school in Berlin. However, private schools in Germany are not as important as they are in other countries. As far as religion in school is concerned, it may be much more important to see how the integration of Islamic education in public schools develops. This process is moving along slowly; however it is ongoing. Some federal states have started to offer Islamic education in the universities, an important step toward the inclusion of Islamic theology faculties alongside the Christian theology faculties that have always been part of German academia.

Bhargava highlights prohibitions against ritual slaughter as another example of discrimination. Here again, reality is more complicated. In Germany, slaughtering an animal without prior anesthesia is generally prohibited for reasons of animal protection. However, exceptions to this rule are granted for reasons of religious freedom. This has been confirmed in Supreme Court rulings of 1985 and 2002 that dealt with the case of a Muslim butcher, and was reaffirmed in a government statement in 2010. It is true that prior to 1985, exceptions were given to Jewish butchers rather than to Muslim ones. And still, there are insecurities when the administrative courts have to decide over such exceptions and over the number of animals to be ritually slaughtered. To speak of discrimination in general, however, does not match the reality. The inclusion of animal protection—like environmental protection—as a constitutional norm was only possible after the Constitutional Court had decided positively over the Muslim butcher’s case in 1985. Here again, the societal debate is highly controversial. Not only animal protection groups, but also right wing groups interpret these rulings as signs of political correctness. Nevertheless, they exist and are practiced.

The third example that Bhargava gives involves the construction of mosques. As far as the law is concerned, such construction is subject to the same zoning and land regulations that govern the construction of other houses of prayer. There certainly is no legal discrimination, and applications to build mosques are usually approved if the formal requirements are fulfilled. However, this does not mean that no problems exist. The announcement that a mosque is planned to be built often leads to protests among the population; and often this protest is fuelled by right-wing groups. In some cases of conflict, the initiators ultimately withdraw their construction plans. In other cases however, the conflict has been given an institutionalized form (for example through public hearings), where both sides were able to express their concerns. As Jörg Hüttermann has shown in his study “the Minaret,” the outcome of these hearings may very well be positive: the conflicting groups begin to acknowledge each other and to envisage concrete persons instead of vague dangers. This institutionalization could be interpreted as an example of direct “state intervention” into majority/minority-affairs (see Bhargava’s essay), but it is rather the moderation of a community process.

I do not list these examples in order to neglect the difficulties that migrants, especially Muslims, are facing today in Germany as well as in other European countries. Discrimination is a serious problem in many of them. However, the examples indicate that things are not as clear-cut as they seem, and that the outcome of current conflicts depends on a variety of factors. Tariq Modood certainly could list further examples from Britain, with its stronger multiculturalist practice, for example the growing inclusion of Muslim chaplains in correctional facilities.

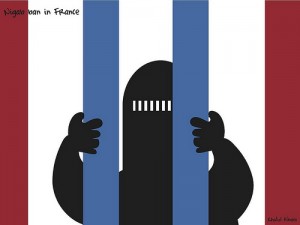

Even France, which has repeatedly been the object of “bashing” due to its “affaire des foulards” and its ban on the public wearing of the burqa, in a not too distant past was widely looked upon as a positive example because of its integrative model of citizenship. The principle of “jus soli” and the practice of integration attached to it were then considered to be much better able to integrate newcomers than, for example, the German principle of “jus sanguinis.” And for quite some time the French model seemed to fulfill this function rather well. Let us not forget that the “affaire des foulards” in the beginning was not simply a majority vs. minority conflict. The headmaster of the school in Creil who prohibited Muslim girls from wearing headscarves in the classrooms was himself a migrant from the Antilles. One could say that he sought to uphold a principle under which he himself was able to succeed. And the school, up to then, had been quite successful in integrating minorities. Even here, the minority/majority relation seems much more complicated than the language of discrimination indicates.

This does not imply that I consider the ban on headscarves in schools or the burqa verdict reasonable. However, the story of Creil and its results remind us that it might be useful to take the cultural memory of a society into account in order to better understand the dynamics underlying struggles over religion and secularity. Due to such cultural memory, these struggles themselves have a normative imprint that is perceptible in the way people respond to certain phenomena—in what they defend and what they attack. Normativity here comes into play as part of the reality itself, as something that we need to understand in order to grasp the social dynamics of the reality under investigation. Max Weber has called this “Verstehen” and saw it as a prerequisite for attempts at explanation. This does not mean that we need to like what we get to see. But my impression is that approaching the reality already from a normative perspective limits what we get to see, because we put things into ready-made boxes of discrimination and non-discrimination.

I do not question the value of normative theory for legal and constitutional concerns, and for political theory, even if this is not my field of expertise. For empirically grounded comprehension and explanation of societal and political processes, institutions, and practices, however, it seems to me that its use is limited. In this respect I do not see how the substitution of meta-languages, which Veit Bader suggests, would make much of a difference.

My colleagues and I, in a research group at the University of Leipzig, suggest an approach to the variety of relations between the secular and the religious through the lens of “multiple modernities” and their respective “multiple secularities.” This approach attends to the diversity of cultural conditions and prerequisites of institutionalized secularity as well as to the impact that the encounter with certain “Western” types of modernity has had. Further, it considers the diversity of cultural embeddings of secularity and the guiding ideas that are connected to them. As a first step, we distinguished four types of secularity: secularity for the sake of individual liberty; secularity for the sake of balancing religious diversity; secularity for the sake of societal integration and national development; and secularity for the sake of the independent development of societal sub-spheres. These are ideal-typical distinctions, in reality they may overlap and conflict with each other. However, as ideal types (not normative ideals) they may help us better understand some of the driving forces of the conflicts that we face. Secularity—in this perspective—is value-laden in reality, because it is “about something,” and this explains its blind spots as well as the fierceness of some present conflicts. If the differentiation between the religious and the secular is motivated by the guiding idea of individual liberties, other motives (like group interests or national integration) may remain in the background or even be neglected. If, on the other hand, secularity is guided by the idea of accommodating group diversity, individual rights or the independence of societal spheres may in turn be neglected. These assertions could be illustrated by a variety of different constellations in countries or regions. One could also identify “critical junctures” (Kuru), in which dominant patterns and motives undergo change: The Netherlands seems to be a good example of a shift from a focus on group balance accompanied by an early debate on tolerance and by practices of non-interference, toward a focus on individual liberties, accompanied by a strong process of secularization in the population, and finally a shift toward issues of national integration and progress with an accompanying secularist ideology. This example shows that secularity can change its meaning under certain conditions.

This, however, is an empirical enterprise, and these concepts have to prove their usefulness in research and theorizing. The Indian case—in its empirical reality and with its normative underpinnings—is definitely one of the most interesting cases of secularity (in our terminology) for the sake of balancing religious diversity. But this does not make it a normative model for Western European societies. They will follow their own paths, whether we like it or not.