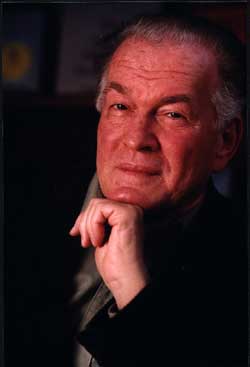

Gene Sharp is the foremost strategist of nonviolent social change alive today. He holds a doctorate in political theory from Oxford and has had positions at Harvard University and the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. Books like The Politics of Nonviolent Action and Waging Nonviolent Struggle, together with numerous pamphlets and other writings, have inspired and guided popular movements around the world for decades. They have been credited, most recently, as a major influence on the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt. He continues his work as Senior Scholar of the Albert Einstein Institution, which operates out of his home in East Boston.

Gene Sharp is the foremost strategist of nonviolent social change alive today. He holds a doctorate in political theory from Oxford and has had positions at Harvard University and the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. Books like The Politics of Nonviolent Action and Waging Nonviolent Struggle, together with numerous pamphlets and other writings, have inspired and guided popular movements around the world for decades. They have been credited, most recently, as a major influence on the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt. He continues his work as Senior Scholar of the Albert Einstein Institution, which operates out of his home in East Boston.

* * *

NS: What was the first thing that crossed your mind when you heard that President Mubarak had fallen from power in Egypt?

GS: That it can be done. In past years, there have been a lot of misconceptions about nonviolent action. People used to think that it was very weak and that only the violence of war could remove extreme dictators. Here was another example that shows this myth isn’t true. If people are disciplined and courageous, they can do it.

NS: Did anything surprise you about how the events unfolded? Did it teach you anything new?

GS: One thing that surprised me were the numbers, and the spread of people participating—that’s just amazing in itself. A second thing was that, in Egypt, people were saying they had lost their fear. That’s a step Gandhi was always calling for, and one that even I thought was a little too hopeful. But that seems to have been what happened in Egypt. When people lose their fear of an oppressor’s regime, the oppressor is in deep trouble. A third thing was how well they maintained nonviolent discipline. We heard reports on television that, when there was an area where things were getting a little difficult and might break out into violence, people were chanting among themselves, “Peaceful, peaceful, peaceful.” That was quite amazing too.

NS: How direct an influence do you think your ideas had on the organizers of the protests in Tunisia and Egypt?

GS: I would like to know! I don’t.

NS: Were you in any kind of contact with organizers there?

GS: No.

NS: Or with people who were in contact with organizers there?

GS: We might have—years ago—met with somebody. But no direct contact.

NS: To what degree do you think these revolutions in Egypt and Tunisia were spontaneous and unexpected, as opposed to being planned and orchestrated in advance?

GS: One of my colleagues has been doing a study of the Tunisian case, so I know a little bit about that. It happened as a result of courageous action by somebody who died and inspired others to protest, and that aroused more protest. It spread from the poor areas far away from Tunis until it finally got up to the capital, without advance planning and apparently without too much detailed knowledge of nonviolent struggle. It appears that in Egypt it may have been a very different situation.

NS: Do you have a sense of what made the Egyptian people choose a nonviolent approach? Do you think it was necessity of the moment, or a prior commitment?

GS: It should have been a necessity. If a dictatorship or highly oppressive regime has all of the troops and weapons, and you’re in the opposition, it’s stupid to try fighting them on their own ground, with their own weapons. You must choose something else. But people don’t always do that—they sometimes try to use violence anyhow, which usually produces disasters.

NS: Were you concerned about the outbreaks of violence among protesters, like the throwing of stones and the burning of police stations?

GS: Yes. I think there has been a lot of mythology about stones—that they’re largely nonviolent. But they’re likely either to verge over into greater violence, which would be self-defeating, or to intimidate people back into passivity, because their stones didn’t bring down the walls of Jericho.

NS: Do you think that other governments in the Middle East—say, Bahrain, Yemen, and Jordan—will be able to adapt to these tactics and prevent them from being as effective?

GS: They will try, inevitably. And those governments will be consulting among each other, probably with the governments of Iran, China, and other places where they don’t like this kind of resistance. I would expect that there will be a lot of sharing of information about how they can get rid of this disease of people power.

NS: How significant a factor is internet technology? Do you think it has been over-emphasized by the media?

GS: I don’t know very much about technology, unfortunately—I’ve been busy with other things instead! All of the reports are that it’s played a major role in both Tunisia and Egypt. What matters, though, is not the technology itself, which is a tool of communication. It’s what you communicate. That’s where my work has been focused.

NS: How has media coverage in general about the revolutions seemed to you?

GS: It seems that it played a very large role. But there are still some problems with the journalism. For example, if there has been a violent repression, or if somebody gets killed, they call it a violent demonstration. But it wasn’t the demonstration that was violent—it was the regime that was killing people. Also, sometimes, they say something is a riot when it is actually a disciplined, nonviolent demonstration. The terminology is very important.

NS: While watching the coverage, many of us were struck by the images of Muslims and Christians protecting each other while praying. Do you think religion was a significant factor?

GS: Not from anything that I have found so far.

NS: Nonviolence and pacifism have often been historically associated with religions, like Jainism and Christian “peace churches”—

GS: Yes, that’s right.

NS: Is religion at all essential to motivating nonviolent movements, or can the ideas transcend their religious origins?

GS: It’s not even a question anymore. They have transcended religious boundaries. If people come from any particular religious group and are inspired to be nonviolent and to resist—not just to be nonviolent and passive—that’s fine. But don’t claim that they have to believe in a certain religion. Historically, for centuries and even millennia, that has not been true. Nonviolent struggle, as I understand it, is not based on what people believe. It’s what they do.

NS: But don’t cultural differences make some societies more likely to act nonviolently than others? Or is everybody equally equipped to do so, independently of their culture?

GS: Setting culture aside for the moment, not everybody is equally equipped to do anything. But when The Politics of Nonviolent Action was first published in 1973, the famous anthropologist Margaret Mead said in her review that what I was maintaining—without saying so, in so many words—was that this is a cross-cultural phenomenon.

NS: There have certainly been stereotypes suggesting that Muslims couldn’t do something like this, that they can only use violence.

GS: It’s utter nonsense. In the North-West Frontier Province of British India, the Muslim Pashtuns, who had a reputation for great violence, became even braver and more disciplined nonviolent soldiers than the Hindus, according to Gandhi. It’s a very important case. And when my essay “From Dictatorship to Democracy” was published in Indonesia, it carried an introduction by Abdurrahman Wahid, a Muslim leader who later became president.

NS: Are you concerned about whether Egyptian Islamist factions will be reliable partners in bringing about a more democratic society?

GS: I don’t really know Egyptian society, much less Egyptian Islamists. But I do know that the Muslim Brotherhood is interested in nonviolent struggle, and several years ago it became—to my knowledge—the first organization in Egypt to put “From Dictatorship to Democracy” on their website in Arabic.

NS: How about the military, which has now taken control in Egypt?

GS: Again, I would have to know the Egyptian military. I don’t.

NS: But, historically, when a military has taken control, has this purveyor of violence become a trustworthy caretaker of nonviolent revolutions?

GS: Not reliably. There’s always the risk that when they get control of the government, they’ll stay, thinking that they know better than the rest of the people. That’s why it’s really important to be prepared for the contingency that there will be either a military or political coup. We have a small booklet on how to prevent coups d’état, and how to resist one if it’s attempted: “The Anti-Coup.” It’s on our website. I’d strongly recommend that people worried about a military or political coup study that and act on it.

NS: What do you think the pro-democracy activists in the Middle East need to do now to ensure that the transition really happens as promised?

GS: Anyone in that situation would need to keep their eyes out and identify what might be danger signals—ways things are moving that are not good in terms of developing and protecting what democracy they’ve gained. They have to figure out in advance what to do when that happens. But we don’t give more specific advice than that.

NS: Why don’t you give advice?

GS: We don’t know these other societies in depth and, therefore, if we gave advice, it would probably be wrong. We do give a kind of advice about the need to think things through ahead of time. We have another booklet on our website, “Self-Liberation,” which is a guide for how people can become competent to plan their own strategies. They have to know their own society in depth: What’s the nature of the regime? Where is it strong, and where is it weak? That’s more complicated than it sounds. They have to know nonviolent struggle in depth, or they can’t plan competently. And, finally, they have to be able to think strategically. Like military strategists, they must plan carefully how to conduct their campaign—not just a battle, but a campaign, in the long term. Mostly, people don’t know how to think strategically, but they need to learn.

NS: How widely disseminated do you believe these ideas have to be? A large percentage of the population in Egypt, for instance, is illiterate.

GS: Sometimes people who are literate are a problem, because they can become tools of whatever propaganda is printed and circulated, and the people who are illiterate are not going to be able to read the propaganda. They’re a little safer!

NS: But do you think that a whole society has to know about nonviolent action before they’re able to undertake it, or can just a small group of leaders have that expertise?

GS: It’s basically very simple: either you do something you’re not supposed to do, or you don’t something you are supposed to do. It’s based not on turning the other cheek, but on basic human stubbornness. Anyone can do it. People don’t have to have a Ph.D. or anything like that to participate. But if you’re going to be planning a strategy for a whole nation, it requires you to know more than that simple principle. We have books that are very long and detailed, and heavily footnoted, and we have things that are maybe ten or fifteen pages, with very simple points. You’ve got to speak to various levels of interest and education.

NS: What do you think is going to be the legacy of the revolutions in Egypt and Tunisia for nonviolent action elsewhere in the world?

GS: I don’t know. I really don’t. Things spread, especially in the days of technology. But I really don’t know. We don’t have people doing research on the spot. We should have had researchers working full time on this for all these days and weeks, but we don’t have the money to do that, unfortunately. We’re not well-funded. We may have been attracting the world’s attention, but we’ve barely been able to scrape by and do our basic work, for lack of money. There have even been these rumors around that we’re CIA or something, but people who’ve visited our office hear that and burst out laughing—our office is so obviously poverty-stricken! This phenomenon needs more major research.

NS: What do you envision this research would like like? What questions would it take up?

GS: Can people power and nonviolent struggle consistently bring down dictatorships and other oppressors—and, if so, how? What are the key things they need to pay attention to and what are the key ways of acting? What must they avoid? It’s my research into this phenomenon that has enabled me to do all these things and write more practical treatises, like “From Dictatorship to Democracy.” Interdisciplinary studies of this phenomenon and of dictatorships and oppression are very important, and I hope that organizations like the SSRC will give grants to people to do that kind of study. Time after time, I’ve come across people who really want to do work in this field and are competent to do it, but they can’t because they can’t get support. If the SSRC could make this a priority for research, it would get the eternal gratitude of the future.